On the frigid evening of Friday, February 3, 2023, at around 8:50 p.m., a Norfolk Southern freight train measuring more than a mile and three quarters long snaked its way through the town of East Palestine, Ohio. The train consisted of 149 cars, pulled by three locomotives—two at the front, one in the middle—and traveled just under 50 miles per hour. Of those 149 cars, 20 were tankers labeled with hazardous-materials placards. Several of the tankers contained liquefied vinyl chloride gas, the combustible and carcinogenic precursor material for PVC pipe; others contained ethylene glycol, a toxic ingredient in antifreeze. Driving the lead locomotive was Tony Faison, the train’s engineer; with him were the train’s conductor and a trainee.

Engineers chart their progress by designated mile markers along the track. About twenty minutes earlier, the train had crossed mile marker 69.0, just east of Salem, Ohio. While crossing that spot, an infrared sensor built into the track called a “hotbox detector” had reported elevated temperatures on one of the front axles of the twenty-third railcar. The ambient temperature that night was 10 degrees Fahrenheit. The bearings on the axle had reached an abnormally hot temperature of 103. The car, a hopper designed to hold commodities like grain, wasn’t carrying hazardous materials, but the hotbox detector relayed an alert to Norfolk Southern’s Atlanta command center all the same. No further action was taken.

As the train left East Palestine, it approached Ohio’s border with Pennsylvania, passing within a few hundred feet of the State Line Tavern, a local watering hole. There, at 8:55 p.m., it crossed mile marker 49.8. As the twenty-third car crossed the next hotbox detector, the infrared sensors revealed that the temperature of the axle’s bearings had risen sharply, to over 250 degrees. Faison immediately received an audio message from the locomotive’s onboard computer to stop the train. He reacted quickly to apply the brakes, but it was too late. He didn’t know it, but for the previous forty minutes, his train had been on fire.

The train took more than a thousand feet to come to a stop. As it did, the compromised axle gave way. The left-side journal box, which held the axle in place, broke off and landed on one side of the track; the wheelset, consisting of the axle with two steel wheels mounted at both ends, ended up on the other. The twenty-third car jumped the rail, and the cars behind it followed suit, creating a tremendous series of crashes that could be heard throughout town. Thirty-eight railcars piled up, including eleven of the hazmat tankers.

Faison leaped from the locomotive to inspect the damage. From his standpoint at the front of the train, he could see flames rising into the night. He immediately contacted 911. So did many of the town’s residents, reporting both the train crash and the fire. One thought a gas station had exploded.

In the next few hours, the toxic flames would force an evacuation of the town. The specter of chemical poisoning lingered over East Palestine for months. And even today, the question of how a system of detectors—expressly designed to prevent this kind of derailment—failed to notice a dangerously overheated train axle remains unanswered.

In the minutes after the derailment, first responders rushed to the blaze, but they were initially underequipped. Serving a town of fewer than five thousand people, the East Palestine fire department was a mostly volunteer force. The sole professional on staff was Chief Keith Drabick, who on that night was almost three hundred miles away, driving through Pennsylvania on vacation. Informed of the crash at 9 p.m., Drabick turned his car around and drove straight back to East Palestine, but he didn’t arrive until five hours later. For the first few minutes, volunteers had to fight the blaze alone. Meanwhile, following protocol, Faison cut the first two locomotives from the train and moved them a mile down the track. In the confusion that followed, some firefighters seemed unaware they were responding to a hazmat site and reported to citizens that the burning train cars were carrying only malt liquor.

Some of the train cars were carrying malt liquor, but others contained stronger stuff. As the scope of the disaster slowly became clear, the volunteers were joined by professional firefighting crews from nearby counties, including a special hazmat squad. At 9:45 p.m., concerned about the risks of a vinyl chloride explosion as well as the toxic cocktail of flaming chemicals escaping into the night, officials began evacuating nearby homes. Meanwhile, some of the contents of the leaking tankers began seeping into nearby Sulphur Run, a stream that flowed directly from the crash site through the center of town.

Even before the official order, citizens had started to evacuate. East Palestine resident Jami Wallace had learned of the train wreck from her mother. Wallace, a human resources manager in her forties, had recently gotten engaged. She called her fiancé, who was with a friend at the State Line Tavern. Driving past the burning crash site, he raced home to collect Wallace and their three-year-old daughter. “Grabbed her a couple of changes of clothes and out the door we went,” she told me. “We didn’t even know where we were going. It was the middle of winter and the heater was broken in the car.”

After an hour and a half of firefighting, the Ohio State Police expanded the evacuation zone to one mile surrounding the derailment site. Around midnight, still fearing an explosion, the firefighters retreated. They then began to survey the crash site with aerial drones, in an attempt to determine which specific chemicals were leaking. The survey was challenging: The site was, well, a train wreck, and some of the plastic hazardous-materials placards had melted in the fire.

Eventually, responders determined that three hazmat cars had been physically breached. One contained ethylene glycol, the antifreeze ingredient, which can be lethal in concentrated doses. The other two contained acrylates, used as base ingredients in adhesives and paint. All three materials were burning off, releasing volatile organic compounds into the air. The fire was additionally fueled by nonhazardous but flammable railcar cargo, including several tankers loaded with petroleum lubricants. For days to come, an ominous toxic cloud hung suspended over the site. “You know how smoke, like, moves through the sky? Yeah, this wasn’t moving anywhere,” Wallace said. “It was almost like a green cloud that was, like, hovering.”

Initially, none of the vinyl chloride tankers were breached. (If they had been, a series of explosions might have occurred, and the cancer-causing chemical could have rained down on the town.) Still, five vinyl chloride tankers, containing more than 115,000 gallons of vinyl chloride in total, had piled up in the burn zone. Each tanker had an emergency pressure release valve designed to vent gas into the atmosphere. Over the next few days, as temperatures rose inside the tanks, these valves automatically opened and closed, periodically releasing excess vinyl chloride gas into air—where it immediately caught fire. In one extraordinary display on the evening of Saturday, February 4, one of the tanker valves vented for seventy continuous minutes, creating a spectacular flamethrower.

With the crash site cordoned off and the tankers burping flames, officials deliberated on what to do. One worry was that the release valves on the tankers were starting to suffer thermal damage. Another was that the vinyl chloride inside the tanks might “polymerize,” forming into chains of PVC, which might cause the valves to stick, sealing the pressure in and causing the tankers to blow.

From the outside, the hazmat experts couldn’t be sure if polymerization was occurring. Eventually they settled on two options. One option was to deliberately puncture the tanks and conduct a controlled burn of the vinyl chloride gas. The other option was to wait it out and hope the tanks cooled down enough so they wouldn’t explode. Chief Drabick was presented with this devil’s bargain: Wait, and potentially watch the exploding tanks rain shrapnel and poisonous chemicals on his town, or release mass quantities of vinyl chloride—a known Group A carcinogen—into the atmosphere. “I was given thirteen minutes to make a decision,” Drabick told investigators from the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), the federal agency reponsible for investigating the wreck.

After consulting with his chief officers, Drabick chose to vent and burn. Following an expanded evacuation order, specialists attached explosive charges to the exteriors of five damaged tanker cars. At 4:37 p.m. on February 6, the charges were detonated, sending twin columns of flaming vinyl chloride gas high into the air and obscuring the setting sun with thick, black smoke. The burn continued through the following day; it was not until February 8, five days after the axle on train car 23 had first started to burn, that the fire was fully put out.

East Palestine soon found itself host to another kind of toxic cocktail, one consisting of corporate communications specialists, blustering public officials, government bureaucrats, and enterprising class-action attorneys. Complementing this splendid company were the more respectable representatives of the NTSB. Leading the agency’s efforts was Ruben Payan, an NTSB veteran with a heavy build, a thick mustache, and a calm and measured voice. Under his patient command, the NTSB began a thorough investigation of the crash site and the events leading up to the derailment.

The agency published the first investigation update to its website in March 2023. And then on June 22, Payan presented his preliminary results at a public meeting in East Palestine. (It was the first onsite NTSB meeting in six years.) Using security camera footage collected from homes and businesses adjacent to the tracks, Payan was able to present a detailed videography of the train’s final minutes. Between the towns of Sebring and East Palestine, more than a dozen surveillance cameras had captured the train in motion; in ten of those camera feeds, the train was plainly on fire. In true-color camera feeds, the lower axle of the twenty-third car glowed a dull orange color; in infrared camera feeds, it blazed an intense white, throwing visible sparks.

The first two cameras to show the fire were in Salem, Ohio, some 26 miles west of East Palestine. The train passed the first camera at 8:11 p.m., 44 minutes before the derailment. That camera, which overlooked an alley of snow-covered cars, caught the train in the far background, its axle glowing orange. The camera was located six miles in front of the Salem hotbox detector—the one that had sent an alert to Atlanta but did not stop the train.

How had the Salem hotbox detector missed the fire? The cameras clearly showed flames and sparks along the length of the bottom of the twenty-third car, but when that same car crossed the hotbox detector 10 minutes later, infrared sensors registered the bearing temperatures at only 103 degrees. This wasn’t a case of a sputtering fire that started and stopped, either—the cameras along the route showed a steady blaze. The NTSB declined to comment for this story, citing the pending results of the final investigation. Norfolk Southern declined to comment as well.

I put the question to David Farwick, a veteran engineer who commanded trains in Ohio for Norfolk Southern for nearly 40 years. He told me that Norfolk Southern’s systems were well maintained and up to date. “Those hotbox detectors, they’re pretty sensitive,” he said. “It’s not like we were working with 1960s stuff. They were pretty good.” The detectors are positioned among the crossties on the track and use infrared sensors to scan the undercarriage of the train. More than 6,000 are deployed across North America. The sensors on the hotbox detectors line up directly with the roller bearings. Farwick seemed flabbergasted that a flaming train had crossed a detector and not tripped an immediate brake alert. “It blows my mind,” he said.

Regulators have also grown concerned in recent years about how long the trains are getting. Farwick told me trains are growing so long that engineers have trouble seeing the backs of them, even on a curve. I asked him whether the train crew would have known they were carrying hazardous materials. “Absolutely,” he said. Farwick explained that the conductor on each train carries a bound paper manifest of the train’s cargo known as a “consist.” In the event of a derailment or crash, a hard copy of this consist is to be immediately delivered to first responders. But Drabick, when questioned by NTSB investigators, said his firefighters never received the consist directly from the Norfolk Southern train crew: “I do not believe that we had any contact with those individuals,” he said. Drabick was only fully informed of the train’s hazardous contents when he arrived on site hours later.

The other looming question about the crash involves the degree of environmental poisoning East Palestine has suffered. In the months following the vent and burn of vinyl chloride gas, Environmental Protection Agency personnel repeatedly visited the town and surrounding areas to take soil samples. Per the EPA’s website, “the sample results indicate that impacts from the smoke and soot were minimal.” The EPA has also monitored the health of the town’s waterways. In the aftermath of the disaster, the agency recorded more than 40,000 dead fish and aquatic animals in the Sulphur Run creek adjacent to the derailment and burn site. While the agency claims that the creek “has not shown any contaminants at levels that exceed health standards since May 1,” it continues to maintain “Keep Out” signs posted around Sulphur Run.

East Palestine is immediately downstream of the crash site, and many local residents believe the creek has delivered poison into their homes. Two days after the derailment, Wallace returned to her evacuated residence to pick up some medication. “As soon as I pulled into my driveway, it hit me in the face—I started coughing ... until, like, I can’t breathe,” she said. “I look over because I know it’s the creek. I look over, and I see these chemicals free-floating down.”

Wallace told me water from the creek regularly seeps into the basement of her residence, and that she has since relocated. She has pushed for the EPA to start indoor monitoring in East Palestine homes; so far, the agency has declined. In any case, the damages Norfolk Southern owes the town are substantial. In June, Norfolk Southern announced that cleanup costs and injury compensation settlements related to East Palestine would cost the company nearly $1 billion, though it anticipated that much of that cost would be covered by insurance.

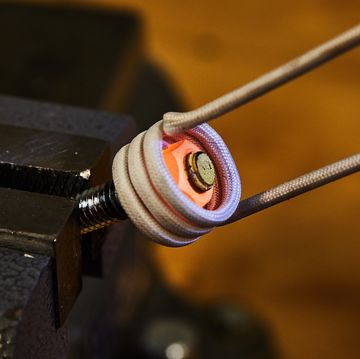

In a statement a couple of weeks after the crash, Jennifer Homendy, the chair of the NTSB, described the accident as “100 percent preventable,” but didn’t offer specifics. She was likely referring to the “hot axle” phenomenon. Train axles use ring-shaped bearings that keep the axle secure while permitting it and the wheels to rotate. A skateboard’s wheels rotate using lubricated ball bearings inside the wheels. Train cars instead use cylindrical roller bearings, which make contact with the axle, permitting easy rotation.

As of December 2023, the NTSB has not yet made a final determination, but multiple experts I talked with told me that they believed a failed roller bearing was the most likely cause of the East Palestine derailment. About two dozen trains derail this way in North America every year. Bearings can fail for any number of reasons, including insufficient lubrication, contamination, overloading, and, simply, age. Once a bearing fails, the axle begins to grind against the metal, and this friction causes a rapid rise in temperature; this was potentially the source of the fire. “Bearings do break down, but that’s the reason why you get these detectors, right?” Farwick said. “That’s exactly what these things are supposed to prevent.”

The roller bearings on train axles are sealed inside the wheel and can’t readily be accessed. A faulty one can easily escape visual detection. Hotbox detectors, by using infrared temperature sensors to monitor the bearings in motion, offer a second layer of protection. Generally speaking, they work. Since the early 1980s, train derailments in North America have fallen from over 7,000 annually to just over 1,000, in part because of hotbox detectors.

The place to catch the failed roller bearing was not in East Palestine, but 20 miles west, in Salem, Ohio, where the train had crossed a detector 30 minutes before the derailment. That detector had recorded temperatures 93 degrees above the outside environment and sent a noncritical signal to Norfolk Southern central command in Atlanta. Whether dispatchers in Atlanta relayed this warning to the train crew remains unclear; the NTSB has yet to publish transcripts from the train’s black box recorder, and Norfolk Southern has refused to discuss the details of the accident.

Perhaps it is worth noting that in the days before the derailment, the East Palestine train had already been delayed twice by stops for unrelated mechanical issues.

In March, the NTSB opened a probe into Norfolk Southern’s safety culture. Regulators were concerned not only by the East Palestine derailment, but also two other Ohio derailments in the surrounding months, as well as separate incidents in which three railroad workers on Norfolk Southern lines were killed in a span of sixteen months, starting in December of 2021. In a statement announcing the investigation, the NTSB urged Norfolk Southern “to take immediate action today to review and assess its safety practices.”

This October, Norfolk Southern unveiled a new layer of protection: giant metal sheds, festooned with cameras, that each train will pass through at various points on its journey. The shed is described as a “portal,” and its cameras take an average of 1,000 images per railcar, and send those images to an AI data center. Deep-learning algorithms are then employed to spot problems that track detectors and overworked railcar mechanics cannot.

Following the derailment, legislators introduced the bipartisan Railway Safety Act of 2023, which proposed decreasing the required distance between hotbox detectors to fifteen miles, from an average of 25 miles today. The legislation is well intended, but it’s not clear if it would have prevented the East Palestine derailment: On that track, the hotbox detectors were an average of 16.7 miles apart. Closing the distance to fifteen miles wouldn’t necessarily help.

The most striking revelation from the NTSB’s preliminary findings was the sheer number of camera feeds that had captured the train car on fire. It costs about $200,000 to install a hotbox detector, and critics have estimated the cost of compliance for the Railroad Safety Act at up to $2 billion. Perhaps wireless video cameras could permit dispatchers and AI to regularly monitor the status of the cars, and would give engineers better visibility to the back of the trains.

Finally, there’s still the problem of the toxic derailment site. It remains a hazard zone, and the nearby State Line Tavern remains closed. Under the guidance of the EPA, much of the topsoil near ground zero was excavated. The soil was supposed to be shipped to a hazardous waste facility in Oklahoma, but that state’s governor, Kevin Stitt, blocked the plan in March. Similarly, the contaminated water from Sulphur Run was drained. The water was supposed to be sent to a treatment facility in Baltimore, but that fell through too. For now, the poisoned water and soil remain at the derailment site. “They have these big Shamu tanks,” Wallace said. “They each hold, like, 100 million gallons of water.” Wallace said a neighbor had flown a drone over the tanks, and seen the chemical sheen on top. Nearby, the toxic dirt has been piled into giant mounds, and covered with tarps. It’s still there.