From Bulgaria to Squirrel Hill: A Holocaust survivor shares his story of survival

For roughly 80 years, Albert Farhy has held onto a button-sized piece of yellow cloth cut into the shape of a star that the Nazis forced him to wear as a teenager in Bulgaria during World War II.

On Monday, the Holocaust survivor held up that fabric — an emblem of Nazi persecution— for roughly 100 high school students in Washington County to see.

The room was silent.

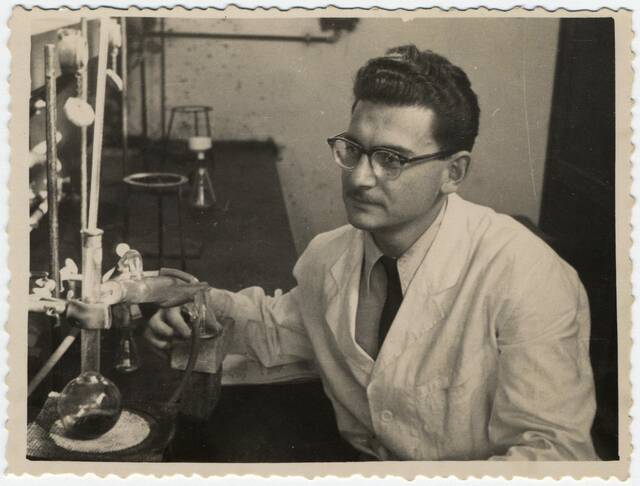

“The Holocaust happened only because of antisemitism,” said Farhy, 94, of Squirrel Hill, a retired chemist who moved to Pittsburgh more than 40 years ago. “Hate is detrimental. It is detrimental to the person who is hating. And it is detrimental to the person it’s directed to.

“It is a disease.”

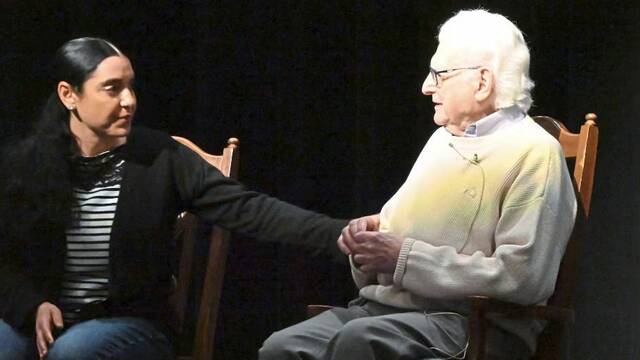

Farhy appeared at Canon-McMillan High School in Canonsburg as a guest of Meg Pankiewicz, a longtime teacher there who had invited the Holocaust survivor to speak with students in her Holocaust and Genocide Studies class.

While Pankiewicz, whose family tree includes Polish and Italian immigrants, is not Jewish, she believes in the importance of her students hearing Holocaust survivors share their stories. She often has invited the survivors to speak with her students, but the pool from which she can pull keeps dwindling in Southwestern Pennsylvania. The Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh estimates there are about 20 living survivors in the Pittsburgh area.

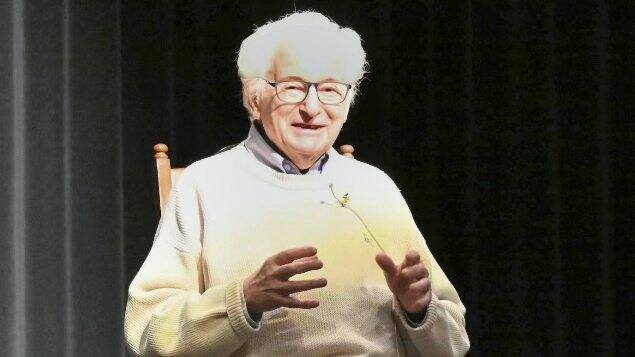

As the teacher sat on stage next to the elderly man wearing a beige sweater and striking, black-framed glasses, a single white auditorium spotlight illuminated Farhy’s face while he talked about his life.

Once like brothers

Farhy was born in Sofia, Bulgaria’s capital, on May 15, 1929, the middle child of Nissim and Karolina Farhy’s three sons.

In July 1940, after Farhy turned 11, the Bulgarian legislature introduced laws prohibiting Jews from owning businesses or intermarrying. The legislation also mandated curfews and wearing the yellow Jewish star, according to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Farhy’s father — who had commanded a machine-gun unit alongside German soldiers on World War I’s Macedonian front — lost his job as a banker shortly after.

Three years later, the Bulgarian government forcibly sent thousands of Jews in the capital, including Farhy’s family, to a ghetto in Pleven, Bulgaria — more than 100 miles away. They had 48 hours to pack and could carry only 55 pounds of luggage, Farhy said.

Antisemitic sentiments roared everywhere, Farhy said. When he walked to school, Farhy passed antisemitic graffiti scrawled on walls — Stars of David that were crossed out.

The government mounted a sign on his family’s front door and those of other Bulgarian Jews. “Jewish home,” the sign read. It also listed every Jew living inside the building, a kind of menacing roll call.

Farhy recalled Monday how he would play soccer with Bulgarian boys in his neighborhood. During one pick-up game, his Bulgarian friend pretended to play for Germany. Farhy responded by playing the role of France.

He later saw the boy in public wearing the Nazi uniform of a Bulgarian youth group.

Farhy’s father, at one point, took the young man aside.

“You are young and you may think this antisemitism has always been like this,” Farhy said his father told him. “It is new. Jews and Bulgarians once were like brothers.”

Two birthdays

By winter 1942-43, the Bulgarian government had arranged with the Third Reich to deport 20,000 Jews to occupied Poland, according to the Washington, D.C., museum’s Holocaust Encyclopedia. Another 11,000-plus Jews were turned over to Germany. Virtually all of them were killed in concentration camps’ gas chambers or shot.

News of the deportations reached Bulgaria’s capital, and groups of elected and religious leaders protested openly against deporting Jews, the Holocaust Encyclopedia said. Several politicians personally persuaded Bulgaria’s tsar to delay the next deportation.

On March 10, 1943, Bulgaria defied German military leaders and refused to deport thousands of Bulgarian Jews to the concentration camps — an act of defiance.

Farhy said he later was told by a fellow Holocaust survivor that the fellow survivor had two birthdays: The day he was born. And March 10, 1943.

“Bulgarian officials stepped in to prevent Albert’s deportation,” Pankiewicz told the students. “His story is rare and ever so timely. … We must ignore social constructs and understand that we are all part of the same earthly community.”

Before Allied forces thwarted German dictator Adolf Hitler’s aggressions in Europe in 1945, his Third Reich had killed 6 million Jews. Millions more toiled in forced-labor camps, faced persecution or lost their jobs, homes and possessions. Most, like Farhy, were ordered to wear the yellow Star of David to identify themselves.

Jews, though, weren’t the only victims.

Between 1933 and 1945, Nazis killed about 3.3 million Soviet prisoners of war, 1.8 million non-Jewish Poles and up to 500,000 Romani men, women and children derogatorily labeled as Gypsies, according to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. They also killed 250,000 to 300,000 people with disabilities, including at least 10,000 children. Possibly thousands of gay and bisexual men, or men thought to be homosexual, also were killed.

By 1948, more than 35,000 of Bulgaria’s 50,000 Jews had emigrated to British Palestine, a part of which became the state of Israel in 1948. Most of the rest left by 1950.

Farhy, too, moved to Israel after the war and then immigrated to the U.S. in 1961. He married in California in 1966 and raised two children.

Around 1970, Farhy became an American citizen and moved to Pittsburgh later that decade.

Fighting hate

Today a resident of Squirrel Hill, the center of Jewish life in Pittsburgh, Farhy said he still sees in the U.S. the virulent forms of antisemitism he encountered during World War II — and not just in events such as the Oct. 27, 2018, Tree of Life-Or L’Simcha synagogue shooting that occurred in his neighborhood.

Sitting in the audience with the teenagers on Monday were two survivors — Carol Black and Audrey Glickman — and Jodi Kart, the daughter of one of the victims. Eleven Jewish congregants were killed that Saturday morning during a Shabbat service. A jury convicted their killer last summer and sent him to death row.

Black survived by hiding in a closet. She was standing near congregant Mel Wax when he was fatally shot. Black’s brother, Richard Gottfried, also was murdered in the attack.

Black said connecting with survivors like Farhy is therapeutic for her. She said the two had a “knowing moment” together.

“The Holocaust happened a long time ago, but it’s history these students have to know,” said Black, 72, of Cranberry Township, Butler County. “What we experienced was not to the same scope … but it all stems from the same root: antisemitism. We have to all do anything we can to fight hate in all of its ugly forms.

“I don’t know how anyone could listen to his talk and not be moved.”

Power to change lives

As Farhy spoke — his voice calm and steady, the occasional curl of a vowel revealing his eastern European roots — some students wept. Others took notes. Afterward, Farhy hugged several teenagers and told them he loved them.

Eamon O’Donoghue, a Canon-McMillan senior, told TribLive after hearing Farhy’s stories that the survivor’s testimony was “more surreal than anything.”

“To see somebody in person and hear it two feet away from you, it’s definitely something you don’t get to witness all the time,” said O’Donoghue, 18, of Canonsburg.

“The fact that his own country said, ‘Something’s wrong with this’ and then helped him to get free, I think that’s really cool,” added Kiersten Williams, a 16-year-old junior from Canonsburg.

Pankiewicz told students that Farhy’s stories have the power to change lives.

“We must remember that those who experience trauma live differently. They love differently. They teach us to live and love differently as well,” Pankiewicz said. “It is my hope that being in the presence of these formidable human beings today will cause you to walk out of this building a different, but better, person.

“Today marks the day that all of you become witnesses,” she added. “Today marks the day that your moral obligation begins.”

Correction: Jodi Kart is a daughter of one of the victims of the Tree of Life shooting in Pittsburgh on Oct. 27, 2018. A previous version of this article incorrectly stated her relationship to the incident.

Justin Vellucci is a TribLive reporter covering crime and public safety in Pittsburgh and Allegheny County. A longtime freelance journalist and former reporter for the Asbury Park (N.J.) Press, he worked as a general assignment reporter at the Trib from 2006 to 2009 and returned in 2022. He can be reached at jvellucci@triblive.com.

Remove the ads from your TribLIVE reading experience but still support the journalists who create the content with TribLIVE Ad-Free.