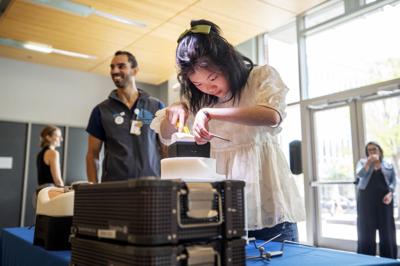

Everly Sharp, 19, takes a metal probe off the tray and pokes at a cross-section of the brain while the screen in front of her suddenly swings into focus on an intricately detailed view of tiny blood vessels on the brain surface.

The high-resolution imaging system is one reason she is now seizure-free but can also still move around, said her neurosurgeon at Shawn Jenkins Children's Hospital at Medical University of South Carolina. Freed from a daily flood of assaults on her brain, her quirky and endlessly curious personality is finally emerging, said her mother, Penny.

She calls it "a gift to be able to know your daughter."

The Sharp family, from Summerville, was on hand for Innovation Week at MUSC, when the university and its health system show off some of its cutting-edge collaborations and advances. One of those is the Modus exoscope, or external digital imaging system, made by Synaptive with input from MUSC Health surgeons.

Dr. Sunil Patel illustrates how surgeons use 3D glasses to operate a new exoscope.

Microscopes have been used for decades in delicate surgeries, particularly in neurosurgery, to see minute structures as surgeons navigate through tricky areas. Most have been worn on the head like an external set of glasses for the surgeon to peer through.

During the surgery, "you are always tilting your head" to get the right angle to see into the field where you are working, said Dr. Sunil Patel, chief of neurosurgery at MUSC.

The area must also be well illuminated.

"Magnification and lighting are very important when you are doing small operations," Patel said, particularly in the brain and spine.

But with the external system, with a camera and light on a long, flexible stalk, the system "peers into the holes that you made" and tracks with the surgeon's hands as they move through the area, he said. The surgeon can look up at a "massive screen" to see the magnified view as they progress through the operation. With the Modus system, there is the option for the surgeon to don 3D glasses to view the screen, adding depth to an already sharp picture of where they are.

Without the constant strain of craning the head and neck to get the right angle because the camera system is moving the view instead, "you're not as tired," Patel said. Instead of averaging three cases a day on surgery days, he is now doing six.

Dr. Ramin Eskandari, chief of pediatric neurosurgery, operates a new exoscope during a demonstration at Medical University of South Carolina’s Drug Discovery Building on April 16, 2024, in Charleston.

It is also allowing Patel and others to reach difficult places in the brain. One of his specialties is in treating tiny cysts on the pineal gland, deep in the center of the brain. Because of the improved vision, what used to take several hours to tunnel to during an operation, "I can achieve that in one hour," he said.

Dr. Ramin Eskandari, chief of pediatric neurosurgery, uses a medical instrument specific to the new exoscope during a demonstration at Medical University of South Carolina’s Drug Discovery Building on April 16, 2024, in Charleston.

It is a sign of the partnership with Synaptic that the feedback from MUSC doctors gets results, said Dr. Ramin Eskandari, chief of pediatric neurosurgery at the children's hospital. If doctors suggest ways to tweak the system, engineers might be on campus the following week.

When Patel "said we need a longer pointer, we got a longer pointer," Eskandari said, holding up a probe. "MUSC had a hand in that. That's really cool."

He demonstrated the newest version of the system, the Modus X, where some departments had been working with a previous version, the Modus V. That earlier version, compared to looking through a microscope, is like going from analog television to high definition. But the newest version would be more like a 4K television, he said. It doesn't lose resolution even when it is at 140 percent magnification, Eskandari said, noting bits of dust illuminated on the brain model where it was focused. It can show nerves and blood vessels that are "submillimeter" in size, he said.

It shows details and structures a surgeon "couldn't see with the naked eye," Eskandari said.

That is very important in brain and spinal surgeries, where what is not cut during an operation can be just as important as what is, Patel and Eskandari said.

"If you can see better, you can avoid injuring them," Patel said.

That not only allows the procedures to be safer, it allows the surgeon to develop greater confidence in what they are seeing and the decisions they make based on that, Eskandari said.

"What you need as a surgeon is trust in your equipment and trust in your people," he said. That in turn can help engender trust from the families.

Penny Sharp said that was important before deciding to go ahead with the difficult surgery for Everly. She suffered a stroke sometime around birth and was left with a number of complications, including up to six seizures a day. It hindered her development and often left her sleepy, with a poor appetite, and affected her ability to learn. But they met with Eskandari and discussed her case for two years before deciding to go ahead with surgery for Everly in August 2022.

The seizures and the damage they caused had gotten to the point where "it was our last option for her," Penny Sharp said.

Penny Sharp holds her daughter Everly’s hand as she explain how an exoscope helped her daughter at Medical University of South Carolina’s Drug Discovery Building on April 16, 2024, in Charleston.

A critical part of the Synaptive system is the ability to do an overlay on the screen of where in the brain are the vital tracts that control voluntary movement or things like speech, Patel and Eskandari said. In Everly's case, it was showing a strip that controlled motor function close to the part of the brain that was to be removed — the area that was thought to be the source of the seizures. Other testing disputed that strip was important, Eskandari said, but he trusted the system and left it intact.

It paid off.

"That's why she can still move and walk and talk," Eskandari said.

Everly has not had a seizure since, her mother said. And once they stopped, it was like watching her grow up and see the world anew, her mother said.

"She doesn't stop talking," her mother said, while Eskandari nodded. Behind them, Everly was still working away on the equipment and called out, "Hey, I fixed your brain for you."

Before, "I had not heard her have a conversation" with anyone, Eskandari said. Her long-dormant personality was emerging and her parents realized "we didn't really know her," Penny Sharp said. "This is really her. She's really funny."

And curious.

Every question is "why, why, why," her mother said. It's as if she is suddenly noticing "things she never paid attention to before" because her brain was under assault, she said.

Everly has gone up three grade levels and can now sit down, be handed a written test and answer the questions.

"She can read, and it's mind-blowing," Penny Sharp said.

But there are also physical improvements, particularly on her left side. Everly has always had problems on the left, particularly with her hand.

“That hand has always been kind of a helper,” her mother said. “She really didn’t have a grip” with it. But after the surgery, Everly squeezed her finger with it. Eskandari noticed that Everly picked up the probe with her left hand, and he is encouraged by it.

"She sees the improvement, and it is motivation for her to keep trying," he said.

Penny Sharp looks at her daughter and it is almost as if she is growing up before her eyes. Everly got a phone six months ago and now FaceTimes her mother "100 times a day," she said.

Everly has wandered over to a chair to look at her phone while her mother and neurosurgeon are talking. She strikes up a conversation with some other people standing nearby, suggesting they all go off to Chick-fil-A.

"I can leave my mom behind," she joked.

Penny Sharp holds back tears as she expresses gratitude to the medical team that treated her daughter for seizures after a demonstration of the machine used in the procedure at Medical University of South Carolina’s Drug Discovery Building on April 16, 2024, in Charleston.

That is part of her now, insisting on doing things for herself, her mother said. There could have been a very different outcome from the surgery, she knows, without the equipment, without the neurosurgeon who rewarded her trust.

"I'll never be able to repay that," Penny Sharp said. "Ever."