Mireya’s Third Crossing

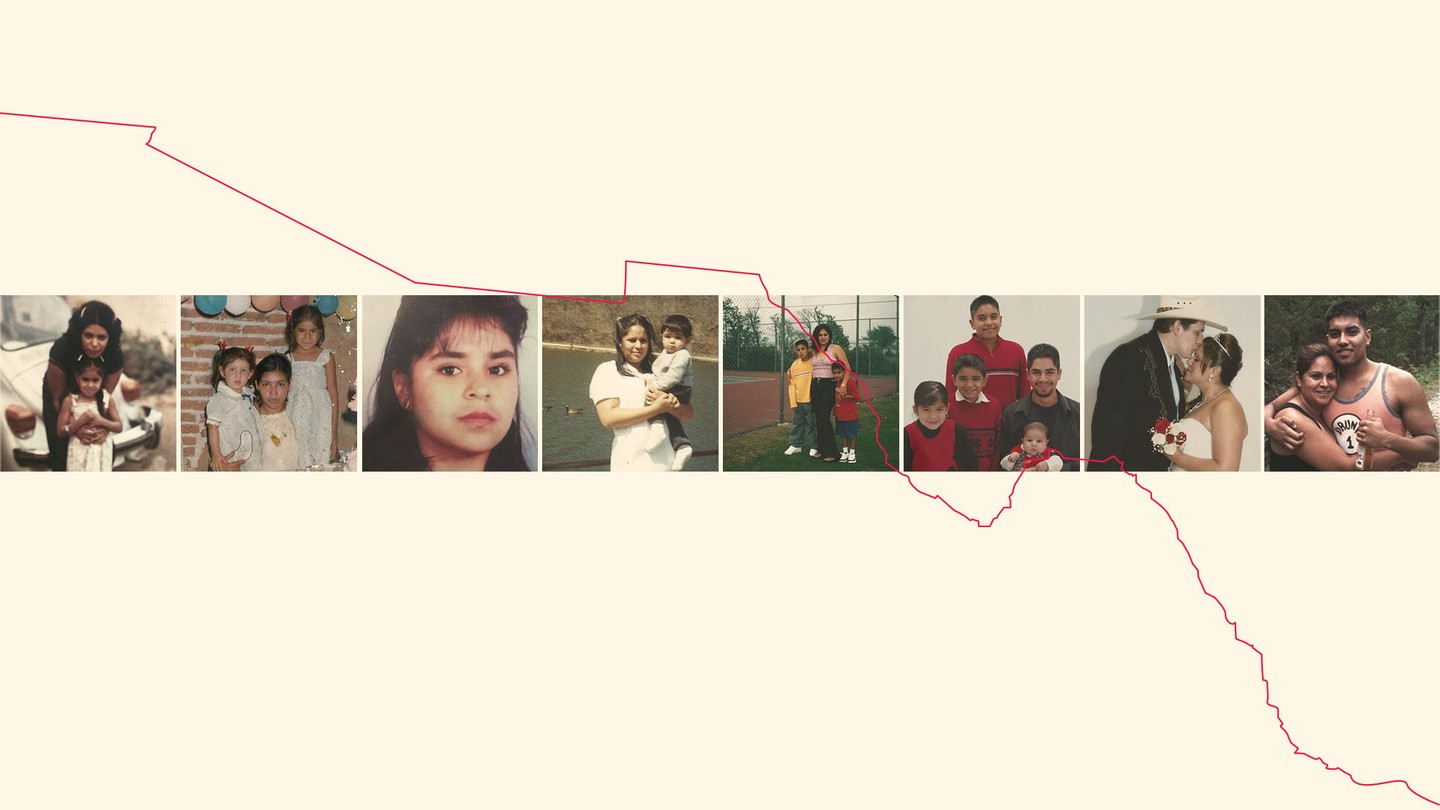

The first time, she was raped. The second, she nearly drowned. In order to live in the United States legally, she had to leave her family and attempt to cross the border once more.

In January of last year, Mireya called me to say she was going to Juárez.

She had been living undocumented in the United States for 25 years, but now she was applying for permanent residency. The final step in the years-long process could be done only at the U.S. consulate in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico.

There, Luz Mirella Zamora (she spells her name with a y to avoid confusion; it is pronounced Mee-ray-ah) would stand across from a State Department employee with three stacks of papers: green, blue, and pink. If Mireya received a green slip, she’d get a visa and return to her husband and children. Blue and she’d have to stay and collect missing paperwork. Pink and she would be stuck in Mexico until her extended family could pool enough money for a smuggler to bring her home: $8,000 to hide in the back of a vehicle, $15,000 if she wanted to sit in the passenger seat.

Mireya had only 30 days to come up with the money to travel to Juárez for her appointment, and from her voice on the phone—victorious, hilarious—I could tell she had some kind of madcap plan. In fact, there had been a minor windfall: A cow had slipped in the mud and broken its leg, and its owner had asked Mireya and her husband to end its suffering and salvage the meat. They went around the house and found $9 in coins, filled the truck with some gas, and drove out to the farm. Robert put the animal down, and they dressed it in the pasture. Now Mireya was turning 80 pounds of beef into jerky to sell by the bag.

I told Mireya I would go with her to Juárez. I’d been following her story for a few years, and I wanted to be there to see how it turned out. I was as strapped as she was, but I returned to the Ozarks, where I was born, and finally got around to selling for parts the Volkswagen Passat with a blown water pump that someone had left to my mother and whose title had somehow been signed over to me.

I first met Mireya in 2014.

During one of my trips home to Arkansas, my father asked me whether I knew I had another sister. He sat on the woodpile outside my parents’ trailer, drinking a beer, and spoke in a rapture of the woman he had come to think of as his 10th child, though they shared no actual blood. He speaks fluent Spanish, and he and Mireya would talk through the afternoons in her language.

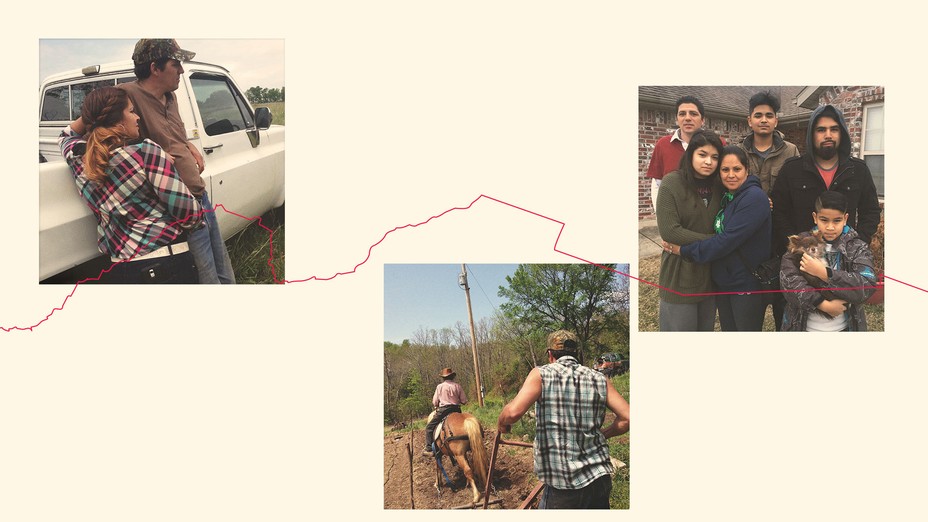

My parents had met Mireya and her five children through her husband, Robert, a third-generation Mexican American who was working in the area. Mireya had grown up in rural Mexico, and she and Robert wanted to go back to the land, in the Ozarks; my mom and dad decided to sell them a few acres of their property on a zero-interest loan.

Mireya and Robert named the place El Rancho and began filling it with geese, mules, and a split-rail pen of pigs. They planned to build a cabin there. Meanwhile, they rented an apartment in nearby Springdale, a cow town when I was a kid, best known for its annual rodeo, that has grown into a small city with the arrival of Latino and Marshallese immigrants. The big businesses in Northwest Arkansas—industrial chicken farms, Walmart, construction—depend on these newcomers for labor.

Mireya’s husband and children are born-and-raised Americans, but she lacked a Social Security number and was forbidden to work. In truth, she worked circles around everyone, keeping the apartment spotless and her kids in new clothes, doing anything from building fences to cleaning houses for cash. When her daughter needed $400 for a French horn and a band trip, she raised the money by selling homemade salsa.

Mireya never knew her real father, but my dad began calling her hija, daughter. She called my parents padre and madre. Among my eight brothers and sisters, I’d always drifted near the bottom of the pecking order. Mireya zoomed to the top. I was surprised to learn that my parents had bragged to her about me, said we were alike, gutsy. But whereas I’d always been deemed rebellious and mouthy, she was “independent,” “direct.”

I liked having Mireya and her family around, but I was furious when I found out she and Robert were two years behind on their payments for El Rancho; they seemed more likely to inherit the property than pay it off. Only one of my siblings has been deeded land, the sole thing of value my parents possess.

Mireya’s uncle had once mocked her for trying to learn English. It meant the world to her when my father, who long ago had taught Spanish at universities (a professor! she told people), praised her fluency. When I attempted to speak Spanish, she cheered on my efforts. But when I began to understand a lot, I sensed that she felt I’d poached something special of hers.

“She’s smart,” I once heard her say to friends, her tone unmistakably rueful. “She’ll learn quickly.”

If we’d been real sisters, somewhere along the way we would’ve had a blowout and cleared the air. Instead, we pulled on poker faces so tight that they began to crack around the edges.

In applying for residency, Mireya feared she would be outing herself to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, which once in a while flags undocumented people for Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Robert didn’t want her to risk it.

But she was tired of hiding, tired of being at the mercy of others’ schedules when she needed a lift to a housekeeping job. A cop catching her speeding could turn her over to ICE. To ride in a car with Mireya was to spot every police cruiser hiding behind trees and learn the unpatrolled back roads.

Until a few years ago, trying to get a visa would have been unthinkable. Under current law, anyone who leaves the U.S. after living in the country without permission for a year or longer must wait 10 years before they can reenter legally. As the wife of an American citizen, Mireya was eligible to apply for an exemption to the 10-year rule, but she would have had to do so from Mexico and then wait there for a decision, a process that can take a year or longer, with no guarantee of success.

In 2013, Barack Obama’s administration provided a workaround: Immediate relatives of U.S. citizens could apply for the exemption without leaving the country as long as they could prove that an extended separation would be a hardship for their family members. Spanish speakers call the I-601A Provisional Unlawful Presence Waiver the perdón. To be pardoned, an undocumented immigrant must prove family ties and pay “forgiveness,” a series of fees.

Mireya didn’t have the $6,000 it would cost to hire a good immigration lawyer, so she decided to go it alone. Every time I’ve told this to someone else who has applied for the waiver, that person has fallen silent.

She joined a Facebook group of 36,000 members, people applying for the perdón and their friends and families. Those who have hit paperwork roadblocks consult the group; others share their lawyers’ advice. Members who are approved in Juárez post selfies with their green slips. They have to wait in Mexico for the consulate to mail their visa, and when it arrives via DHL, they post more selfies with the package, whose red-and-yellow corporate logo has become a stand-in for the documents sealed inside.

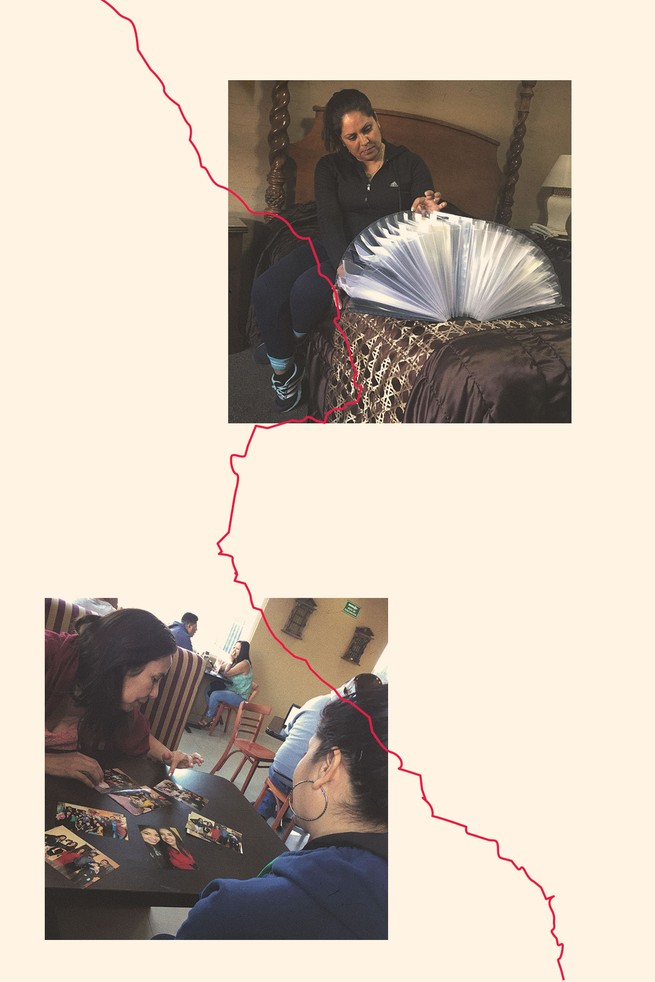

For three years, Mireya collected the required documents, first in a manila folder and then in an expanding accordion file known as “The Folder.” It was black, with 25 titled subfolders, and Mireya decorated its surface with pictures of her family to remind her why she was spending so much time acquiring its notarized contents.

Mexico required that requests for an official birth certificate be made in person. Mireya deputized a distant cousin in Michoacán, her state of birth, and armed her with copies of her and her mother’s birth certificates and Mexican IDs. The cousin went to a courthouse and began negotiations with a judge. A year and $400 later, the new birth certificate arrived in Arkansas. It was in Spanish, of course, and Citizenship and Immigration Services requires all documents to be translated into English, so Mireya paid for that too.

Having no laptop, she filed some forms on her phone, and walked to the public library to print hard copies of others. She put together the Petition for Alien Relative for Robert to file, to establish their relationship, and paid $420. A year later, with the petition approved, she applied for the I-601A waiver. Wanting to make sure she’d ticked every box, she spent $1,300 on a physical exam and vaccinations. The filing fee for the waiver itself was $585.

Her waiver was approved in the spring of 2017; now she would have to go to Juárez for a medical exam and an interview at the consulate. Mireya sought the advice of a low-cost lawyer from a Catholic charity, but the woman dismissed her: Mireya had crossed the border twice—in 1989 and 1997—and if you’d entered the country illegally more than once, she said, your visa application would be denied.

Mireya told the Facebook group what the lawyer had said. If she traveled to Juárez, would she get stuck there, separated from her family for who knows how long? She signed off with “Dios sin mí sigue siendo Dios, pero yo sin él no soy nada”—God without me continues to be God, but I without him am nothing.

Twenty-seven people responded; they concluded that since she had crossed so long ago, she would be forgiven.

We would drive to El Paso, park Mireya’s car there, then take a van to Juárez. Robert and Mireya packed the car at dawn. Itzanai—“Nani”—and Fernando, the teenagers, said goodbye. Clutching the family Chihuahua, Josh, 9, followed his mother around with growing agitation until she sat and held him.

Mireya’s oldest, Joaquín, 25, would drive us. Her second son, Eliseo, had died in 2014. She’d risked her life for him when he was a squalling toddler with a heart problem, crossing into the U.S. the second time, in 1997, so that he could get better medical care. As a teenager he’d been the family charismatic, working in an ice-cream shop and chipping in with bills. At age 18 he was killed in a car accident on a summer morning. Now Mireya mentions her son’s death to strangers moments after meeting them, as though her name is inseparable from the loss.

In her grief, Mireya had let a year pass before returning to her visa application. Donald Trump was voted into office, and in the days after the election girls bullied Nani at school, telling her she would have to “build the wall” herself. Josh’s sympathetic teacher called Mireya to pick him up when he cried and confessed that he was afraid his mom would be deported. Plans to build the cabin halted, but they moved to a rental in the town nearest El Rancho, the largely white and conservative Elkins, population 3,000.

Mireya had left her pueblo the first time at age 15. Her beloved grandmother was already in California, nursing a sick relative. A family friend had been molesting Mireya since she was 11. Fearing she would be raped, she decided to find her grandmother. A girl only a year older but much more worldly loaned her money for a coyote, and said she would go with her. The girl’s cousin joined them. They took a bus 1,500 miles north to Tijuana, where at the time 200,000 migrants crossed every year and coyotes were cheap, $250 to $300. Mireya told me the story; I’ve edited her words for clarity and brevity here.

I didn’t have any money. I didn’t know anything about the United States.

At the bus station in Tijuana, this guy stopped us. “You going to El Norte? I can hook you up, I have friends, you’ll make it in three hours. We got a house where you guys can rest and stay ’til it’s safe to cross.” He keeps on saying, “You can trust me. I’m not going to hurt you.”

We made it to the house.

The upstairs was just a big room with four walls, no windows, and a metal door. No bed, only some sheets on the floor. There was this big lady, she was tall, kind of old, 45 maybe. Her husband was short and fat. They gave us showers and clothes, and they fed us. They put us in the room upstairs, said we’re gonna sleep there and they gotta lock the door for our safety, and if we gotta pee or whatever, they gave us a bucket.

I got that feeling in my heart saying something’s wrong. Why are they gonna lock us in the room? We slept there that night, and then in the morning, we heard a lot of people talking, yelling, partying. We heard steps on the stairs. We’re all happy because it’s time for us to either go away or go—do something, I don’t know. They’re supposed to let us know whatever happens.

Here comes the lady of the house, and she’s just barely wearing clothes. She opens the door and says, “Good morning, my beautifuls, my princesses!”

We just looked at her.

Right behind her come three men, and this guy is looking at me, and he goes, “I’ll pick her.” The other guy is like, “Yeah, I’ll pick her too.” And the other guy—I didn’t know what was going on, but my friend, she was hugging me, and she said, “No, not her, pick me. Let her go. She’s 15.

They took me downstairs, where there was this little room.

They raped me.

That went on for days, nights. And all I got to eat was a glass of milk with an egg in it, raw, mixed in. They say it will give me energy. For days I was locked in that room.

Finally, the guy that brought us over there came in the room and took a look at me and he was like, “Are you okay?”

I couldn’t talk. Said nothing. He took off his jacket and put it on me, because I was naked. He said, “I’m gonna get you girls out of here. They tricked me. They said if I bring more girls here, they were not gonna do this again.”

It was so hard for me to trust him! There were no other choices. I had nothing else. Everything inside me was gone. So whatever comes next, it’s fine. They’re gonna cut me, they’re gonna kill me? Fine. It’s better than this. He opened the door and he told me to stay behind him, and we started walking upstairs. He opened the door where my friends were. They had been raped too. We started walking downstairs, out the back door. He had a car. He opened the trunk, said we’ll be safe there, and then he started driving.

After a while, he let us out and said, “I’ve got a friend, and he’s gonna help you girls cross. He’s gonna take a shortcut.” He told me, “I hope you’ll forgive me for what I’ve done.”

This new coyote said we were gonna walk for two or three hours to this bridge, we’re gonna go underneath it, and then we’re gonna make it to this big fence, and you girls gotta jump off it.

Those three hours became three days that we were walking. I don’t know, maybe we were lost. It was dry and rocky and it was hot. We didn’t have much water—we had to sip it and hold it in our mouths. We ended up sleeping in open fields, and I was so worried about scorpions. I don’t care about snakes but I did care about scorpions.

We finally made it to the bridge and went underneath, and then we kept walking. We saw this big fence on the U.S. side. It was chain-link, 10 or 12 feet tall, like the ones in prison with barbed wire on top. Some parts of the wire were broken where other people had crossed before. My friend knew what to do and climbed up the chain-link and jumped off it. She was on the other side, calling, “Go, go, there he comes, there he comes, you better come soon!”

And we were like, “Who’s coming?”

And she calls, “¡La Migra!”

The coyote started running and disappeared. Here comes the other girl, and whoosh—she jumped off that fence. I was the last one and I’m so afraid, shaking. I don’t know what to do—I don’t know who La Migra is or what they’re going to do to me, so I just started running, and I was getting close to the fence. I climbed halfway up but I couldn’t make it and I fell back. Here comes this big old horse with the immigration guy on it.

He was telling me something in English. I didn’t speak English then; I didn’t know the words. He got off the horse and walked to me with a mean face. He was a big old guy with red hair and blue eyes, really blue eyes. Beautiful eyes. And then he was asking me questions. I couldn’t understand what he was saying, and finally he said it in Spanish: “¿Tu nombre?”

“Mireya.”

“Mireya.”

“Sí.”

He grabbed my face with one hand and looked at me. And he turned me to the fence. “Aquí. Go, go, go! ¡Ve, ve! ¡Aquí!”

I started walking where he pointed. I saw a big hole under the fence—there were branches covering it, but obviously he knew it was there. He told me to go underneath, cross from there. I moved the branches and went through—I was a little girl, skinny—and he got up on his horse and looked at me and said, “Good luck,” and disappeared on his horse, with the dust behind him.

Over here. Go. The Border Patrol officer who let her go—he was an angel, Mireya said. She’ll always remember his face.

The coyote who turned her over to the rapists—she remembers him as an angel for coming back. “I forgive him. I do. It was hard, took me so long. But I think I got over that. I’m a mom, I’m a wife, I love my husband,” she told me. “It’s part of the life that came to me, and I think I handled it pretty good. I made it out of there alive.” Mireya has reconciled the men’s assaults with God: Maybe it was a test, or the price for good things in store.

In California, she found work babysitting for a couple from Africa. The man wouldn’t reveal his name—she thinks he was worried about getting caught employing an undocumented immigrant. Instead he called himself El Negro de Africa. He was the tallest, darkest man she’d ever seen, and he taught Spanish at a university. If she was going to live in America, he said, she had to learn English. He gave her lessons three times a week, a kindness that would change her life. Another angel.

She worked for a few years and gave birth to two boys, but she couldn’t make ends meet. Her grandmother had already returned to Mexico; Mireya decided to follow her. Back in the pueblo, Mireya discovered that Eliseo had a heart problem and needed a specialist. As a U.S. citizen, he was eligible for Medicaid. Mireya set out to join a cousin in Northwest Arkansas; she would then send for her sons. This time she would cross the Rio Grande at Piedras Negras, near Eagle Pass, Texas. She was 23 years old.

There had been heavy rains, and the local TV station was airing reports about migrants who had drowned. Mireya’s family said not to risk it. But Eliseo was sick.

Carrying only her asthma inhaler, some money, and one change of clothes, she took a bus to the border, where she met a group of other migrants. Some coyotes had offered to take Mireya and another woman by land, since they both spoke English and would present well, and to show forged documents to Border Patrol.

The deal was that I was gonna cross in a car, sit in the back seat, and not talk to anybody—they ask for your papers, and you show them. But when I got there our coyote said La Migra was checking everybody really good, so he goes, “We know this place where the river is shallow. The water will go up to your knees. You can’t cross during the day, because that’s when they’re looking for you harder. There’ll be a white van waiting on the other side at a gas station. They’ll take care of the rest.”

It’s like, Hmm. Well. Everybody’s thinking, talking to each other. Some were crossing for their first time, some their fifth. Everyone said, “Well, we gotta do it. There’s no way back.” They drove us to the river in an old black minivan with no seats. But once we made it to the river, we saw it was flowing like you can’t imagine—you’re seeing the sea! I said, “No, I cannot do that. I don’t know how to swim.” And even if I knew, that current was fast.

The guy said, “No, no, no, you’ll be fine. We did it yesterday and the days before.” It was getting dark. He said, “Everybody has to get naked. No clothes, no bra, no panties, nothing. No shoes. It’s just you. Here’s some bags. Throw your clothes in there. And one of us is gonna go to the other side and put the clothes over there. Once you make it to the bamboo on the other side, I’m gonna yell ¡María! three times, and when you hear that, it means it’s time for everybody to get out of the water, get dressed, and go. You gotta do that fast.”

They said if you get out of the water and you’re soaking wet and La Migra sees you, they know right away you just crossed the river. You gotta have dry clothes. They said the floodlights on the river, if you were wearing clothes, they can see that, but if you’re naked, they can’t. At least that’s what they told us.

The guy said, “Girls or guys that don’t know how to swim—these two guys, you gotta get up on their shoulders. He’s gonna be walking with these two long metal bars so he can hold himself in the water, because there’s some places where he’s gonna go completely down, cover his head. The water will go up to your chest.” The bars were taller than the guys—they had to be six or eight feet tall—and they would stick them in the ground really good.

We’re like, “How’s he gonna breathe?”

So here we go: Get in the water. You start the journey, and it’s so—crazy. You can’t see. It’s so dark. And you hear people yelling, screaming, “Please help me!” People are going by you—the current took them. And you feel so bad. You can’t let go of those metal bars and try to grab one of those people.

We made it to the other side, and then the guy who had me on his shoulders came out coughing and puking water. It took him a while to recover, and he told us, “Wait here. We’re going back to get the rest of the people. Wait for the call.” We waited and waited and waited, but that call never came. It was just the noise of the water.

I was the one who said—I could barely talk—“I’m getting out of this water.” It was so cold. I said, “I’m having an asthma attack. I don’t have my medicine. I can’t breathe. I’m not going to die here. No!”

Mireya and the others climbed onto the riverbank, where they found clothing left by other migrants. She walked, barefoot, to the white van at the gas station, wearing a shirt and pants three times her size.

In Juárez, an industry of hotels, restaurants, and fixers has sprung up around the U.S. consulate, the only one in Mexico that processes immigrant visa applications. Mireya, Joaquín, and I decamped to the Conquistador Inn to wait for her appointments.

The medical exam, conducted at a private facility, would be the first and more difficult of her two interviews. Members of the Facebook group had told her what questions she would have to answer, which they believe are meant to trip up applicants, masking judgments of character as medical assessments. Tattoos? What do they mean? DUI—so you have a drinking problem? Mireya would have to confess to tattooed eyebrows and show the butterfly on her lower back—hardly gang symbols, but everyone was nervous about everything. She’d gotten a checkpoint DUI seven years earlier, when she’d had a beer at home before a friend at a party, drunk, called for a ride. And what would the antidepressant, prescribed after Eliseo died, mean?

Inside the facility, she and other women received bar-coded bracelets and took off their clothes. Then technicians X-rayed their lungs to check for tuberculosis. Children? Five. Natural births or C-sections? Natural births, she answered, but they checked her abdomen for a scar. The tattoos and the DUI were discussed and dismissed, and a psychiatrist determined that she was grieving, not mentally ill. Mireya received a sealed plastic envelope to give to her consulate interviewer.

On the way out, she studied the bill. The cost of the exam was $220. The facility had not accepted proof of her previous vaccinations and had administered its own, bringing the total to $445.

Over the next few days a group coalesced in the Conquistador’s lobby, where a holiday atmosphere sprang up, as it does in places of purgatorial crisis.

Miguel had been stuck in Mexico for five months. An X‑ray had showed a spot on his lung, so he would have to pass a series of sputum tests before going home. In California he was a diesel mechanic. He had found a job in Tijuana while he waited, but it didn’t cover the mortgage and bills. He and his wife, Blanca, have two young children, and her uncle gave her gas money so they could drive to Tijuana on weekends and see Miguel.

Yovana and her sister Graciela, 14 years her junior, confounded everyone. Yovana was the U.S. citizen of the two, but strangers assumed the opposite, since she was brown-skinned and her sister fair. Yovana’s parents had divorced soon after she was born in the U.S. Her father had then returned to Mexico, and had Graciela with a light-skinned, hazel-eyed woman. He took Graciela north when she was 3. Yovana, now a dental assistant, had helped their father buy Rite-Aid gift cards for birthdays and otherwise raised her sister.

Graciela has her own small children. She’d put off applying for residency because she was afraid to leave them.

Why apply now? “Because of the president we have.”

A few days into our stay, Miguel walked into the Conquistador’s lobby holding a green slip. People passed the paper around, rubbing it for luck. Miguel sat on a sofa and shook his head. “Creo en Dios.” I believe in God.

Tall, radiant Anabella rushed in the next morning—her visa had been approved! She spread pictures of her grandchildren on a table and gossiped with Mireya. She worried that Mireya’s two crossings would disqualify her.

Most of our group in the hotel had appointments on the same day, and the night before, everyone who was gathered in the lobby agreed to go over together. Miguel and his wife, Blanca, were there, and Yovana and Graciela. Claudia sat next to her husband, their hands on each other’s knees. Oscar showed us a video on his phone of a massive rave he DJ-ed once a year. He’d moved to Brooklyn 10 years ago—his plan had been to save some money and then come back to Mexico and open a business. But he had a baby.

Mireya rose to hold court, speaking in Spanish, telling the folks from California and New York about her garden harvests at El Rancho—the tomatoes, onions, and chilies she made into salsa. “It’s very rare that I shop at Walmart,” she boasted. On her phone she pulled up a picture of a black bear—“and there are dangerous cougars!” She was a jaunty country girl in a checkered work shirt, spooking the city slickers as my brothers and sisters and I used to do. I’d never felt closer to her.

Blanca wondered about the Latino population in Arkansas, jobs, the presence of ICE. Mireya talked about her house cleaning—“For the men, it’s easier, they work in construction”—and explained that in Elkins most of the locals have been welcoming.

“Is it a sanctuary city?” Yovana asked.

“No …”

The rumor was that, in practice, appointments were first come, first served, so the next morning everyone lined up at the consulate before dawn, buying coffee at a corner store. A young man passed around almond cake. Once the consulate opened, those with appointments went inside while the others waited.

Francisco was agitated. He’s a naturalized citizen and works for $13 an hour at a plant in Texas that makes aluminum rotors; their hot edges had burned a ladder of scars up his arms. Now his parents were seeking to join him. He believed his father would be okay—he had crossed illegally but returned 12 years ago. His mother had never crossed, but she couldn’t read or write. Would she get rattled? Could she remember the dates of birth for her many children if asked? He’d written them on a scrap of paper and tucked it in her hand.

We were in desert weather, our feet freezing on the ground, our head and shoulders roasting as the sun rose. A line formed behind us, eventually stretching a couple of blocks.

There was a stir in the crowd—our people were coming out.

Claudia fell into her husband’s arms, her cheeks wet with tears. Approved.

Graciela found her sister and smiled for what seemed like the first time in days. “I can go back to my children now.”

Oscar and the man who’d shared his almond cake disappeared. We heard they’d gotten blue slips.

Francisco’s parents walked up, stiff and formal but with victory in their eyes. Francisco raised a singed arm straight to heaven. “¡Gracias a Dios!” he called, loud enough for Dios to hear.

Mireya came out and found Joaquín. She had a green slip in her hand.

Mireya would wait in her family’s home in Jalisco, farther south, for DHL to deliver her visa. Her aunt had died a few months before, and her uncle Odilón, a handyman, solemn with grief, lived there with his grown sons and their children. He picked us up at the airport in Guadalajara.

Mireya had not been to her pueblo in 20 years. It lies at the foot of a mountain, and a vandalized Spanish hacienda stands at the edge, its interior blue walls open to the sky. Villagers maintain the cobblestone streets. Men working in construction in the States have wired money to have the icons in the chapel leafed in gold, and a man named Alejandro rings its bell with a rope. For a few pesos, an old couple will milk one of their cows directly into your pail.

About 4,000 Mexicans live in the pueblo, along with a few hundred migrants from El Salvador and Guatemala who come there to pick the blackberries and raspberries surrounding the town—most Mexicans couldn’t get by on the wages.

The first night, there was tequila and Coca-Cola under the bougainvillea Mireya’s grandmother had planted decades ago. Her cousins and their families filtered in, piling drinks and tacos on the card table before her, and pulling up chairs. A deliveryman brought Coronas in a bucket filled with ice, and then cracked one open himself and sat down. The younger men talked trash. Mireya sassed back, giving as good as she got, and they screamed with laughter.

Past midnight, the children put themselves to bed, and a cousin turned the radio from mariachi music to something slower. Odilón took Mireya’s hand and she rested her head on his shoulder as they danced.

In the morning, Mireya brought duffels of her children’s hand-me-downs to her childhood best friend, Ana. The women sorted through the pile just as they had in 1997, when Mireya gave all her clothes to Ana before heading to the Rio Grande.

Over the next few days, Mireya walked through the streets, greeting people. “¿Me recuerdas?” Do you remember me?

She bought snacks sold in a doorway and an old woman stepped out. “Do you remember me? I’m Mireya!”

“Mireya! I remember those eyes!”

“My son Eliseo died in an accident. I’m in Arkansas—”

“Remember how I used to take you from your mother when she was beating you?”

Yes.

Mireya walked on. There was the guava tree. There was the clinic where her little brother Alfonso was born. “There are the sheep! So big! See that cactus over there—it produces fruit, but only in May. Ah, pinche madre,” motherfucker, she crooned.

Several days in, the DHL package still hadn’t arrived, and Mireya had gone from dashing international visitor to servant of everyone but Odilón. She rarely left the house, cooking, cleaning, and washing her cousins’ and Joaquín’s laundry, unable to say no.

Mireya and I shared a bed, and Joaquín slept in the same room. Every night mariachi music blared from the patio. One morning Mireya announced that a rat had woken her, and the men and boys of the house tore the room apart, armed with machetes.

My family had passed the hat for Mireya’s travel expenses, but clearly it had gone to household bills. There was no money left to get home. Robert called, desperate for her to return. Mireya told him to rustle up more work and sell some pigs. She would sell homemade tamales as soon as her feet touched ground in Arkansas, if only she could get there.

Mireya was, finally, exhausted. When she was growing up, she said, they were so poor that at Christmas her grandmother decorated a scrub tree with cotton balls and gave each grandkid four candies. That was it. And they’d been happy because they were together.

She fell into solitude.

The men found the rat and a few days later the DHL package came. Mireya called my mom, and she sent money. Mireya, Joaquín, and I flew into Juárez at sundown and found a driver to take us to El Paso. We sat on a bridge high above the Rio Grande, stalled in traffic, the surrounding mountains disappearing as the sun set over a border finally made visible only with brake lights. A vendor walked among the cars, carrying a cluster of fluorescent balloons.

The driver studied Mireya in his rearview mirror and spoke of children who had died of cold in the desert and other grave things. “Cabrones, que bárbaro”—bastards, how cruel—she murmured from time to time, but she was buzzed with forward motion again. Melancholy couldn’t touch her. And I knew that Mexico had made Mireya and me family after all: This journey would tie us.

The driver left us at the U.S. Customs and Border Protection station, a huge room empty at this hour. He would wait for us on the other side.

A Border Patrol officer ripped open the DHL envelope and shook out an inch-thick stack of papers that he kept, and then Mireya’s Mexican passport and U.S. visa. He was heartthrob-handsome, made handsomer because he was shy. He stamped Mireya’s visa with a spring-loaded rubber stamp, one of those big physical things manufactured for the sole purpose, it seems, of sending echoes off the walls.

Mireya walked toward the door that would take her into the United States, where her taxi was waiting, and then she stopped and turned around to gaze at the officer. “He’s another angel,” she said. “I’ll always remember his face.”

This article appears in the June 2019 print edition with the headline “Mireya’s Third Crossing.”