Sid King had just sat down to dinner on September 18, 1980 when he got the call.

King was part owner of KGFL-AM in Clinton, Arkansas. He started the radio station after his previous employer, Dogpatch, a Li'l Abner theme park, went belly-up. At a station that small, King couldn’t afford to specialize. He was also the station manager and news reporter.

The station called King while he was eating at sales representative Tom Phillips’s home. They’d heard on the scanner there was something going on at Missile Complex 374-7, the Titan II Missile installation in nearby Damascus. Possibly a fuel leak.

It had happened before. Two years earlier, a trailer at Damascus leaked oxidizer, the component that mixes with rocket fuel to propel a rocket into space or toward a strategic target. This released a cloud of noxious gas, leaving a few people sick and eager to file lawsuits.

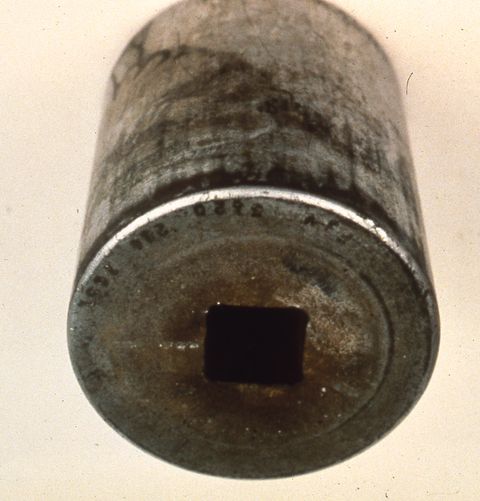

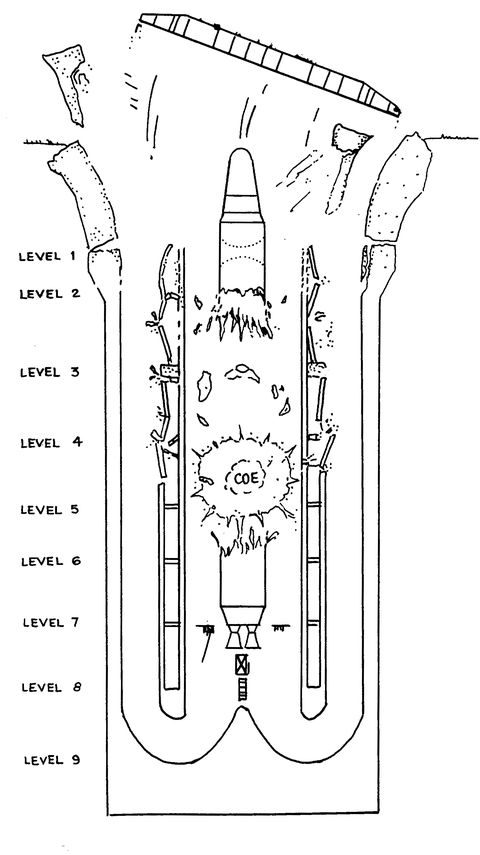

But the site King and Phillips were driving to in their company Dodge Omni was worse. It turned out a worker doing routine maintenance on one of the missiles had dropped a nine-pound socket. This wasn’t the first time; in most instances, it hit the platform. But now, the socket fell all the way down the missile shaft—66 feet—bounced off the shaft mount ring, and hit the side of the missile, puncturing its eighth-inch hull. Fuel vapor started to fill the silo.

“The chances of all this happening were so remote,” David Stumpf, the author of Titan II: A History of a Cold War Missile Program, tells Popular Mechanics. “They tried to recreate it in an empty silo, and it bounced into the wall. It never bounced into the missile.”

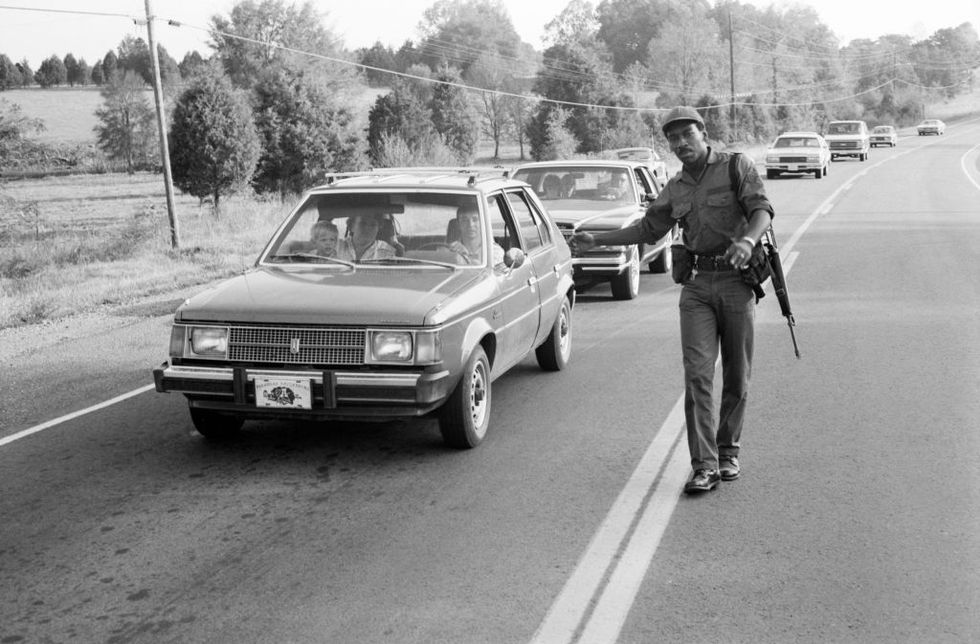

King and Phillips arrived at the site at the same time as Van Buren County Sheriff Gus Anglin, and they were all greeted by military security personnel, who told them no evacuation of the area was necessary at that point. Meanwhile, as a countermeasure, the silo was filling with water to douse potential flames and dilute the vapor.

King decided to hang around. He called the station, and word spread. Within a couple hours, there was a crowd of about 25 to 30 journalists and law enforcement personnel gathered just outside the gate.

Around 1 a.m. on September 19, they watched a helicopter and a bus full of people enter the base. There still wasn’t any official word about what was going on, but they all put on rocket fuel handler’s coverall outfits (RFHCO)—rubberized protective gear that resembled space suits—and walked to the silo, which had been filling with corrosive and potentially explosive vapor for hours.

King remembers sitting on the hood of a sheriff’s car, aimlessly slipping his shoes on and off. “And around 3:05 a.m., all hell broke loose,” he tells Popular Mechanics.

If you saw footage from the massive explosion in Beirut this past August, King says, you saw what he saw that morning. The air turned white and chunks of steel-reinforced concrete fell out of the sky after the fuel ignited. After nearly being run over by the sheriff, King and Phillips jumped in their car and took off.

“We drove maybe 10 miles before we said anything to each other,” King recalls. I said, ‘We just left a bunch of dead people back there.’ He said ‘Yeah, I know.’ We were sick about it. All the guys that walked down with their RHFCO suits, I just assumed they were all killed.”

The Missile

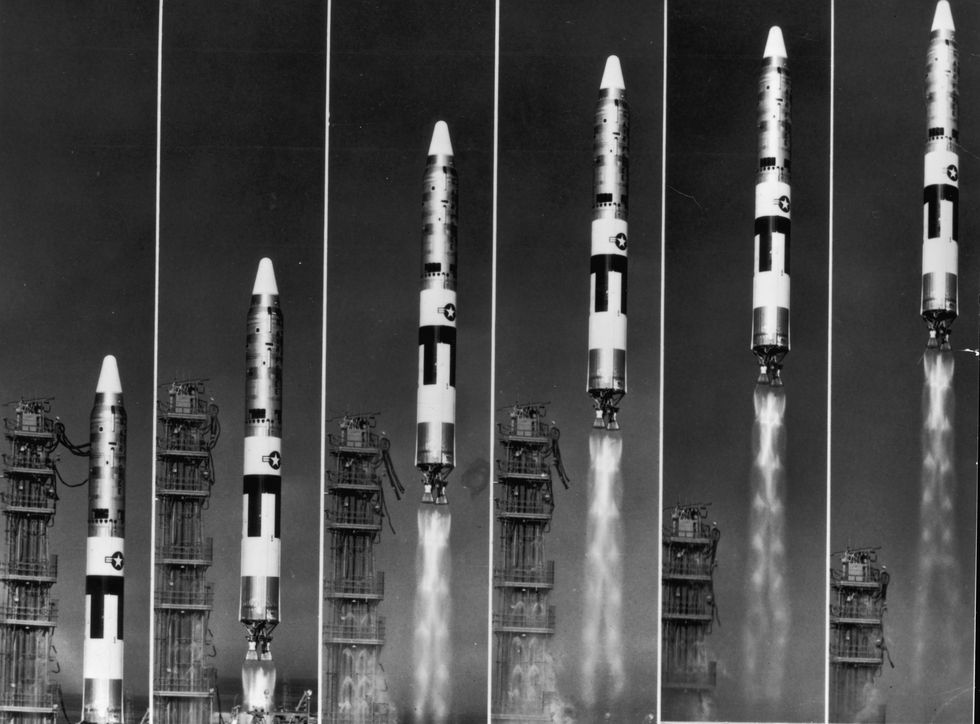

When the Soviet Union launched Sputnik into space in 1957, it made the idea of long-range nuclear bombers obsolete. If a rocket could be launched into space, it could also be launched at something, and far faster than bombers could fly to targets to drop their payloads. If the Soviets had missiles, then the Americans needed them, too.

“The idea is no longer to win a nuclear war, but to prevent one from starting,” Chuck Penson, who recently retired as historian for the Titan Missile Museum in Arizona, tells Popular Mechanics. “That’s the idea of the Titan II. It was sitting there at a moment’s notice, and putting the enemy on notice that they couldn’t win the war.”

The first U.S. intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), like the Atlas and the Titan I, were cryogenically fueled, relying on substances like liquid oxygen, which had to be kept cold. It took about 15 minutes to load the fuel and move the Titan I into position before firing—not a great selling point when every second might count.

The Titan II, on the other hand, had a longer range and could be used for defense as well as for the nation’s nascent space program. “Titan II was developed as much for use in space flight as it was for an ICBM,” Stumpf says. It was used for the Gemini project, which launched men like Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Jim Lovell into space in the 1960s.

A total of 54 Titan II missiles, capable of going from launch to a target 8,000 miles away in about half an hour, were installed in Arizona, Kansas, and Arkansas. (Not coincidentally, the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee at the time the missiles were installed was Arkansas Democrat Wilbur Mills.) Unlike its predecessor, the Titan II used hypergolic propellant, with fuel and oxidizer stored in the missile—at room temperature—and mixed to launch almost instantaneously.

Of course, that’s just as true on purpose as it is on accident.

“The fuel’s so volatile, it could explode on its own,” Greg Devlin, who was a 21-year old Airman in the U.S. Air Force at Damascus on the night of the explosion, tells Popular Mechanics. “But we dealt with hydrazine [the fuel] and nitrogen tetroxide [the oxidizer] every day. We were so used to it that it didn’t scare us.”

☢️ Read Up: The Best Nuclear History Books

While the Polaris, a solid-fuel missile, was developed at the same time as the Titan missiles for use in submarines, the military was attached to the Titan II for diplomatic reasons. The SALT I Treaty, signed in 1972 by the U.S. and Soviet Union, allowed for the Titans to be traded for more missile submarines, but Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev wouldn’t sign the treaty without assurances the trade wouldn’t happen. So the Titans stayed in place—and demonstrated time and again their peril.

In 1965, a civilian welder working on upgrades in an Arkansas silo accidentally hit a hydraulic line, causing a fire that killed 53 of the 55 workers there that day. In 1978, six months after the trailer leak in Arkansas, two airmen died after a leak in Kansas.

The Titans sat fueled and ready to go at a moment’s notice—but that meant constant monitoring and maintenance. That’s why a Propellant Transfer System (PTS) crew was in the silo in the early evening of September 18, 1980, at the end of a long day, pressurizing the fuel tank of the missile (which, in a morbid coincidence, was the same one that 15 years earlier was in the silo that caught fire).

Airmen Jeffrey Plumb and David Powell were in the silo working on the missile. Eric Ayala was “topside,” at ground level near the silo. “There was a lot of white smoke,” Ayala tells Popular Mechanics, “but it was hydrazine.”

The PTS crew stayed at the site as an investigative crew—Devlin, Rex Hukle, David Livingston, and Jeffrey K. Kennedy—arrived. They all knew each other. Ayala said Livingston, a native of Heath, a small town in central Ohio, would let him use his ham radio to talk to people in his hometown in the Bronx.

Kennedy went down into the silo by himself to get readings. The situation was critical. But the investigative crew was in a holding position for a while, and finally, around 1 a.m., Devlin and Hukle went into the silo.

“We’d been there for a while, and we were like, ‘Send us in or send us home,’” Devlin recalls. The initial PTS team was sent home. “If we hadn’t been ordered off, we would have stayed,” Ayala says. “We didn’t want to leave, but I understand why they wanted us to leave.”

The Blast

Devlin and Hukle weren’t certified to work a hydraulic pump, Devlin recalls, and were unsuccessful in trying to manually open a blast lock door. After a half hour—they could only stay in the silo that long because of their oxygen tanks—they came back up. This time, Livingston and Kennedy went down.

“They realized it was way worse, not worse than we felt it would be, but probably worse than a lot of other people thought,” Devlin says.

On the way up, Livingston and Kennedy were told to turn an exhaust fan on. In his official statement in the investigation, Kennedy said it didn’t make sense: “Why would you energize an electrical circuit in a fuel leak?” Livingston flipped the switch and then came topside. “The main theory is that when the vent switch was pushed, it sparked the explosion,” Devlin says.

About a half-mile down the road, Sgts. Jimmy Roberts and Donald Green saw the explosion. “I turned to Sergeant Green and said, ‘Man, ain’t that pretty,’ before I realized what it was,” Roberts said in a statement during the investigation. “Then we realized what it was and started grabbing for masks.”

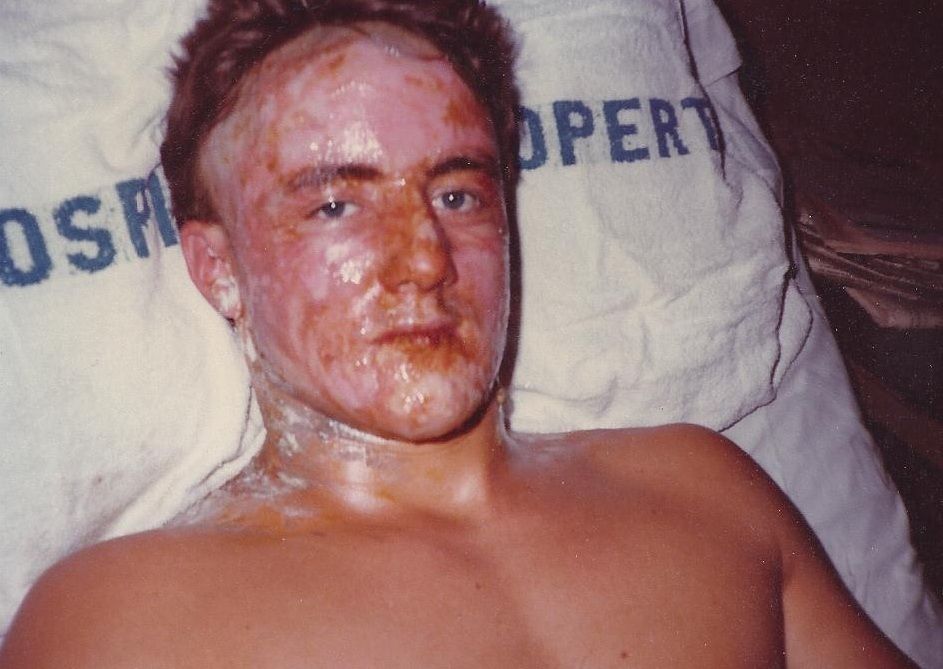

The four men at the silo were blown off their feet.

“It was the loudest explosion I’d ever heard in my life—before or since,” Devlin says. “A concussion of wind hit me like a truck, and I slid 60 feet, and every foot, it felt like I was going faster. The only thought I had at that point was, ‘I know I’m a dead man. I just hope it doesn’t hurt.’”

After what seemed like an eternity of silence, Kennedy could be heard on the radio saying, “I’m dying.”

Rex Peters was up to get a blood pressure pill. He’d worked on the Manhattan Project and had retired to Damascus after years in Los Alamos, New Mexico. He saw the explosion, and he told the New York Times his first thought was, “It kind of reminded me of the old days. For a minute, it was the same deal as an A-bomb.” But Peters realized it wasn’t a nuclear explosion, because he had time to think.

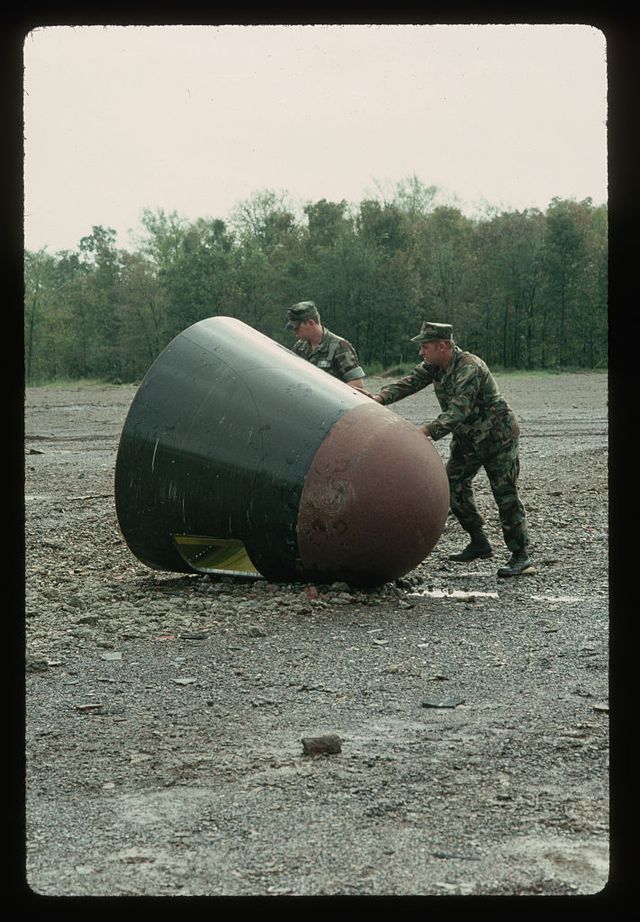

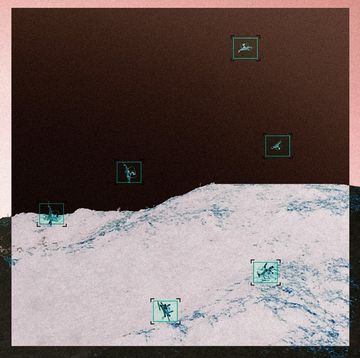

The explosion blew the silo blast doors off and sent chunks of debris flying everywhere, including the nine-megaton nuclear warhead that sat atop the missile. (By comparison, the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima was around 15 kilotons, and the one dropped on Nagasaki was around 21 kilotons. There are 1,000 kilotons in a megaton).

KGFL, Sid King’s radio station, had a daytime-only license, but this was a big enough exception that King was on the air by 3:30 a.m., “telling everyone to get the hell out of there.” By 4 a.m., the studio was full of people and a flurry of activity. “They don’t know where the warhead is,” King recalls being told.

Eventually, it was found—in a ditch about 200 yards away from the silo. Not that the Air Force was sharing that information.

The Air Force refused to confirm or deny if a nuclear weapon was involved in the explosion—even to Vice President Walter Mondale, who was in Arkansas that day for the state Democratic convention, trying to help the state’s young governor, Bill Clinton, in a re-election bid.

Frustrated, Mondale had to call Secretary of Defense Harold Brown and pull rank, saying, “Goddammit, Harold, I’m the vice president of the United States,” to find out it was, in fact, carrying a nuclear warhead. And Mondale then refused to confirm or deny when he was asked about it at the state convention.

The Aftermath

The Damascus incident was front page news for at least a few days. Then it faded into relative obscurity. Miraculously, only one person died: Livingston, in a local hospital the day after the explosion of pulmonary edema, sometimes called dry drowning. (Kennedy died in 2011 at the age of 56.) But the effects of the explosion and working with the potentially toxic fuel linger for many of the airmen who were on site.

Devlin, now retired in Florida and a children’s book author, says he has osteoporosis and believes the hydrazine he inhaled caused it. “I have a thyroid condition,” Ayala says. “Nobody’s saying it’s from that, but nobody else in my family has a thyroid condition.”

Mondale and Jimmy Carter lost their bid for re-election in 1980. It was morning in America, and the Ronald Reagan administration undertook massive military spending—including missiles to supplant the Titan II. While these missiles were retired in 1987, the company that made them, Martin-Marietta (by then Lockheed Martin) took them back and reconditioned them for space use. They were used to launch satellites into space as recently as 2003.

While researching what was going to be a book about warfare in space, journalist Eric Schlosser heard the story of the Damascus explosion. By then, a lot of the documents detailing just how bad the incident was—and how close we’d come before to accidental nuclear explosions —had been declassified. The Cold War was over, and with it the threat of annihilation … right?

“This isn’t ancient history,” Schlosser, who wrote Command and Control, the seminal book about the Damascus incident and the history of nuclear weapons in America, tells Popular Mechanics. “There’s a real risk right now. The Doomsday Clock is at 100 seconds to midnight.”

The odds of a city being destroyed “are probably the highest since World War II,” says Schlosser. “Extremist groups like to destroy cities. Nuclear weapons are just ideal for that.”

Penson’s warning is even more ominous.

“The next nuclear bomb to go off will not be delivered by a missile. It’ll be in a port in a shipping container or something like that.”

Vince Guerrieri is a writer based in the Cleveland area. He's the author of two books, and his byline has appeared in Deadspin, Jalopnik, CityLab and POLITICO, among other places.