Sometimes when a woman says “I am impossible”, it’s just classic, sappy, feminine self-deprecation. It’s like saying, “Oh, this old thing?” when someone compliments you on a frock you have spent a long time thinking about and even more time saving for. Sometimes, though, when a woman says “I am impossible,” you should believe her.

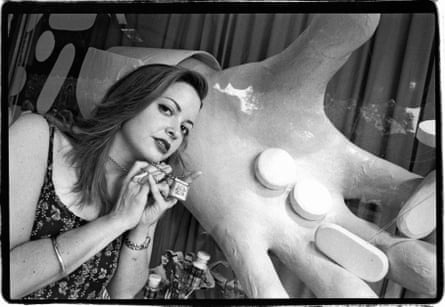

Elizabeth Wurtzel was impossible. I believed her. I briefly experienced her being so. She came to London to promote Prozac Nation, the memoir that would make her famous, the best book she wrote, which was about the “United States of Depression”. She demanded to meet certain people: writers including Martin Amis, Julie Burchill and Will Self were on her list. She also wanted sex and drugs. She picked at her food in a restaurant in Soho that was somehow not good enough. A lot of things were not good enough for her. We ended up in the Groucho Club, where she draped herself over various men, magazine editors. Huge, kohled eyes; long blond hair; a tiny vest top. She already had an FTW (Fuck the World) tat. She was both irresistible and very annoying and she knew both these things about herself.

The night involved crystal meth, a man, and her paying the huge bill – which was magnanimous, except that she demanded that my friend, who was on a lowly publishing wage, pay a 50% tip.

I guess she wanted to be like the rock stars she had idolised and written about and slept with. Indeed, the bits in Prozac Nation where she bangs on and on about Bruce Springsteen are rather dull. Her subject was not music, it was only and always herself. Her hurt.

Kurt Cobain may have shot himself in the 1990s, but we still didn’t talk much about depression and self-harm back then, and if we did, it was as a vague social issue. Economically, these were boom times, remember.

Wurtzel’s memoir – angry and narcissistic – was maddening in itself. When she turned up in her freshman year at Harvard, as the US author Deborah Copaken wrote in The Atlantic: “Suddenly there she was, fresh off the train from her yeshiva in New York, suitcase in hand. She didn’t look like a yeshiva girl. Or even really like a New Yorker. She looked like a Malibu-born-and-bred hippie even back then, with her straight blond hair, her perfectly worn-in Levi’s, her giant eyes that drew you in and threatened to drown you.”

Soon, everyone knew who Lizzie or Liz was. She was “campus famous”, throwing a party when she lost her virginity. So how, then, was she in such pain, and how did she write about it so viscerally? For that is what she did. How can one be clinically depressed and yet self-assured enough to write a memoir that would open up a whole conversation about mental health? “Some things are beyond repair,” she wrote “And that was me.” Clever and beautiful, why was she the way she was? To some critics, she was simply too self-indulgent. Why was she so shameless about her self-harm, her drug-taking, her promiscuity? Why did she not hide as women are meant to? Why not 30 years of therapy and suffering in silence? No.

She fell in love, she said, with her own depression, as she thought so little of the rest of her. Her agony justified her existence. Perceptively, she would report from the unknowable frontline where feeling nothing is much the same as feeling intensely. A world where she would grab things. Often men. “I would then end up with nothing and then mourn the loss of something I never had.” Sex was an attempt to shut her brain down and open her heart out. I witnessed her in that mode and, really, did any guy stand a chance? She was in love with them within a day. It looked like someone bleeding out.

But she was also very funny. On Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, in which the protagonist, Esther Greenwood, decides not to wash her hair any more, she wrote: “You know you have completely descended into madness when the matter of shampoo has ascended into philosophical heights.” Prozac Nation made her an It girl in New York, and this was warranted. For her level of self-exposure was courageous. Of this I have no doubt.

Inevitably, though, the magazine editors whose laps she perched on would ask her to pose nude. For she was one hot mess, this young woman. There she was, semi-naked in GQ, as though depression was sexy and made women available. I was both puritanical and appalled by this, but now I see that this was her choice, pre-internet, a branding of the fantasy dream girl: intense, neurotic, beautiful. The precursor to the essentially harmless manic pixie dream girls of more recent times. Wurtzel was not one of them, for sure. She was damaged and she would do damage.

Her selfishness was part of her. A friend of mine took her to a debate at the Oxford Union, which she had asked to go to; my friend needed to get back the next day because her father was dying in hospital. Wurtzel refused to get out of bed. “What’s the problem? He isn’t dead yet.” He died a week later.

After Prozac Nation, she published Bitch: In Praise of Difficult Women, for which she posed topless again on the cover, middle finger raised aloft; and, in 2001, the memoir More, Now, Again, which is largely about her addiction to snorting Ritalin. These books were less successful than her debut. Unedited confessionals no longer cut it. So she did something really quite amazing – went back to law school and trained as an attorney.

The fact that her stories became somehow less resonant was surely because she had helped to open the door to a series of confessionals about bad and difficult women doing bad and difficult things. Magazines and newspapers were and still are stuffed full of young women confessing to bad sex, eating disorders and mental health issues of every variety. This is not meant facetiously. For the more we talk about mental health, it seems to me, the less we resource actual mental health care, whether through talking therapies or understanding medication properly.

Depression as an issue of culture, of essential alienation – as, indeed, a logical response to late capitalism – is raised occasionally, but policy runs shy of making these connections. Of course it does. Mental illness must always be individualised, which is why the title of Wurtzel’s book, Prozac Nation, is still so powerful.

The drugs of choice now are opioids – OxyContin or something similar. Anything that takes the edge off the pain. Wurtzel got this. She got it absolutely, and so have a string of other writers since, from Lena Dunham to Phoebe Waller-Bridge, who would tell us that being a young, clever woman, however privileged you are, is a world of pain. You can call that pain self-indulgent if you like, but it can’t be fucked away as Peaches has suggested. It’s real.

Ultimately, when Wurtzel was diagnosed with breast cancer – which many would see as a real illness, while some still see clinical depression as imaginary – she was remarkably without self-pity. No sympathy cards for her. “Where were you when I cried my eyes out for 10 years?” she asked her friends. She advised everyone to get tested for the BRCA gene mutation that many Ashkenazi women carry, but she wrote: “Everyone else can be afraid of cancer. I am not. It is part of me. It is my companion. I live with it. It’s inside of me. I have an intimacy with cancer that runs deep.”

She later declared: “Do you know what I’m scared of? Nothing.

“Cancer just suits me.”

The disease killed her. Another woman who felt unlovable, but was loved and feared for her refusal to grow up and conform, for her searing honesty, no matter how unpalatable that was. No homilies from her about peace. She was a star in her own drama.

Everyone else was just a bit player. You knew that as soon as you met her. But impossible women can be like that: unlikable, difficult and then immensely and suddenly loyal and kind. She refused to hide her pain or make it digestible for others.

That was her radical selfhood. Scary, exhausting and thrilling. “I am preternaturally truthful,” she once said. That is not an easy life to live, but my God, I am glad she told us exactly how it was to be who she was. The pain and the glory. Lizzie.