A new federal program pitched as a way to aid low-income communities is ramping up across Louisiana, but after a political scramble to make various struggling areas eligible for the tax break, it's investors and real estate developers who are starting to reap the benefits.

Last year, more than 150 census tracts in Louisiana were designated as Opportunity Zones under a provision in the 2017 tax-cut bill designed to encourage investment in economically hard-hit areas.

A year ago, Republicans and Democrats finally agreed on something: the Opportunity Zones program. Speaker of the House Paul Ryan, a Wisconsin …

With Gov. John Bel Edwards responsible for selecting from the nearly 600 eligible census tracts in Louisiana, public records show local officials, small-town mayors, businesspeople and even U.S. Rep. Cedric Richmond lobbied the governor via the state's economic development office on which areas should be chosen.

The designation from the office of Louisiana Economic Development was highly sought after because it could translate into potentially millions of dollars in tax savings for anyone who recently purchased or is willing to invest in properties or businesses in these areas.

The local surge in interest echoes a national boom. Louisiana supporters of the initiative are touting early successes, while financial firms are creating investment funds and figuring out rules that are still under development.

At the same time, even some business-minded observers worry that the program won’t help people in poor areas so much as accelerate gentrification or add additional tax savings to projects that would have happened anyway.

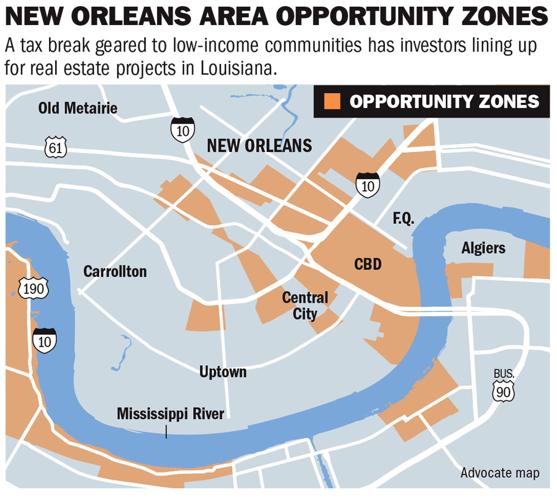

New Orleans' booming Freret Street corridor is now an Opportunity Zone, as are the struggling streets just a few blocks away. Investing in either spot will offer the same tax break.

“Will it be a results-blind tax haven?” asked Rob Lalka, head of the Lepage Center for Entrepreneurship at Tulane University. “Or will it be an opportunity to really move capital toward key projects that are going to matter for the community?”

Opportunity Zones were added to the $1.5 trillion 2017 tax cut bill by South Carolina Republican Sen. Tim Scott, based on a plan developed at a think tank funded by tech investor Sean Parker.

The idea was to create tax benefits for investors to help fund businesses in areas skipped over during the current economic expansion.

Under the program, instead of paying capital-gains taxes when selling a high-flying stock or a hot piece of property, investors can defer taxes on their profits by reinvesting into a property or business located within an Opportunity Zone.

By holding onto the investment for several years, they can receive a discount on those deferred taxes when the bill eventually comes due. And if they hold the investment for more than 10 years, there are no capital-gains taxes on the profits of that new investment.

The tax break has no cap on the amount of benefits allowed each year. There are also currently no reporting requirements.

Up to 150 high-rise apartments will be added to downtown Baton Rouge with the redevelopment of the Chase South Tower, giving the central busin…

Skepticism said 'justified'

Investors and developers are jumping at the opportunity, and while many advocates for low-income areas are optimistic, they worry whether the benefits will accrue to neighborhoods and communities in need of investment.

Chris Tyson, the head of the East Baton Rouge Redevelopment Authority, said during a recent panel discussion that many efforts have been made to redevelop poor areas in the past, but they didn’t necessarily transform the areas as intended.

“If you’re skeptical, it’s justified,” Tyson told the group of officials and business owners. “We want to know what’s going to be different this time.”

The program is expected to cost the federal government $1.6 billion in the first decade, but most of the tax breaks are expected in the years after that, meaning the cost to the government could rise.

Another potential hiccup, according to tax-law analyst Samantha Jacoby of the left-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, is that the program does not include any requirements that local residents benefit from the investments.

Wealthy people, not poor people, are the ones who have capital gains, she noted. And areas that are already attractive to investors are getting the benefit, such as the New York City neighborhood where Amazon has announced its intention to build a new headquarters.

"While the new tax break enables investors to accumulate more wealth, it includes no requirements to ensure that local residents benefit," said Chuck Marr, a colleague of Jacoby at the CBPP, where he focuses on federal tax policy.

When the law was being crafted, Tulane’s Lalka said it was pitched as a way of enticing people to invest in start-ups and small businesses. But since it’s been enacted, real estate has dominated the activity surrounding the program.

Rules for a federal Opportunity Zone program that aims to boost private investment in low-income areas are expected to be released at the end …

Influx of recommendations

In Louisiana, the nominating process was a mad dash that included lobbying from countless economic development agencies, politicians and businesspeople across the state, all hoping to get their land or their district included.

Developer Buckner Barkley, owner of Marrero Land & Improvement Association, made several recommendations on where to put the zones, requesting that the Edwards administration put them in areas where the company owns property.

After the governor picked two of his nine recommendations, Barkley has more than 300 acres of land in an Opportunity Zone near the former Avondale Shipyard site.

Barkley, whose company has made several donations to state Senate President John Alario of Westwego, requested that Alario support his request. “Our company has real estate holdings in each of the nine census tracts shown on the plans,” said his letter. “I would appreciate it if John could bring this matter to the attention of the governor.”

Alario’s office sent it on to the governor.

"Marrero Land is a major landowner in the West Bank," Alario said in an interview, adding that the request was the only one his office received. "We hoped if they were selected it would create jobs."

Alario said that if anyone else had contacted him requesting a tract be included, he would have passed it along to the governor's office also.

Richmond, who represents most of New Orleans and parts of Baton Rouge in Congress, lobbied for a host of tracts in his district.

James Bernhard, a staffer for Richmond, wrote to the governor’s office in March that Richmond had “personally compiled” a list of census tracts for the program. He also talked with Edwards about it, according to the email.

"Because of my knowledge of the creation of Opportunity Zones, as well as my familiarity of the neighborhoods in my district, I wanted to ensure that I had input in the selection of the census tracts," Richmond said in a statement. "It is important to me that programs like this one best meet the needs of my district. The legislation was written with congressional input in mind. I also believe that the governor and I were on the same page with this issue."

After the nominations were over, LED Secretary Don Pierson wrote back to Richmond, notifying him that the tract that encompasses Louis Armstrong International Airport in Kenner, which Richmond recommended, was not eligible. However, he wrote, the tract directly north of the airport was eligible and made the list.

The federal government has certified the 150 census tracts nominated by Gov. John Bel Edwards as Opportunity Zones, which will offer tax incen…

Wide-ranging zones

Sidney Torres III, who is part of a group of investors who own the old Ford plant in Arabi, is hoping the fact the property is now located in an Opportunity Zone will help attract someone to redevelop the 225,000-square-foot building.

Torres, an Edwards campaign donor, said he did not lobby for the tract to be included.

Pierson said the administration solicited multiple rounds of public comment when picking the zones, and it studied which areas were likely to see economic activity if nominated.

Zones are also designated in Walker, on land that includes a 127-acre tract that local economic development officials are trying to sell to investors; an area in Terrebonne Parish where the Isle De Jean Charles community is being relocated from its sinking coastal home; and tracts in Caddo and Jackson parishes.

Much of New Orleans’ Central Business District is now an Opportunity Zone. So too is the largely undeveloped area upriver from the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center, where tourism officials and local developers Joe Jaeger and Darryl Berger hope to build a $558 million, 1,200-room hotel.

Land adjacent to that proposed development, the site of a massive defunct power plant owned by Jaeger, is also in the zone.

Records show it is not a low-income area, but it was designated as an Opportunity Zone anyway under a provision of the law that allows some areas “contiguous” to low-income areas to receive the designation.

Troy Villafarra, managing director at the New Orleans-based investment firm Crescent Growth Capital, recommended those areas get the designation.

Troy Villafarra, who heads up the Opportunity Zone program for Crescent Growth Capital, poses for a portrait in his office in the New Orleans Central Business District, Thursday, Jan. 31, 2019.

His firm has already raised $16 million for an opportunity fund and plans to raise as much as $60 million annually. While he isn’t involved in the hotel project, he hopes to piggyback off the development via nearby properties.

In Baton Rouge, all of downtown and parts of the city’s Mid City corridor, which has in recent years attracted a rush of investment, are enveloped in Opportunity Zones.

Anthony Kimble, one of the developers of the Electric Depot redevelopment in the fast-growing Mid City area, said he hopes to use the new tax break for part of the project.

A few blocks west of Electric Depot, on the corner of 3rd and Florida streets downtown, real estate broker Jim Allen is marketing the State National Life building for sale; he is touting the Opportunity Zone designation of the area.

Toll revenue would pay for only 17 percent of a new bridge across the Mississippi River in Baton Rouge, a top state official said Tuesday.

A fruitful real estate deal

Among early movers, perhaps no one timed things better than Baton Rouge developer Mike Wampold.

Last February he purchased the 21-story Chase South Tower in downtown Baton Rouge with a plan to turn portions of the office tower into luxury apartments.

The first apartments in I River Mark Centre, the new name for the redeveloped Chase South Tower, could go on the market by June.

Three months later, he sold 144 Elk Place, a former office building in New Orleans’ CBD, for $27.6 million to a Florida company that sells timeshares and manages vacation properties.

Both properties are in areas recently certified as Opportunity Zones.

“We basically took the gains to sell that building and created our opportunity fund,” Wampold said.

“It just so happened we acquired the Chase South Tower in 2018, and it just so happened we were selling a building in New Orleans in 2018,” he said.

Wampold said it remains to be seen if this program will differ from the many existing tax incentives out there. More distressed areas will likely see some Opportunity Zone projects, he added, but it’s not going to “change the face of real estate development.”

144 Elk Place photographed in New Orleans, Thursday, Jan. 31, 2019. A vacation rental company purchased the 144 Elk building from Mike Wampold last year. Wampold is putting the money towards the renovation of the Chase South Tower in Baton Rouge to get tax breaks through the Opportunity Zone Program.

“I think you’ll see more activity in areas that have the ability to support new construction,” Wampold said.

Villafarra said the Opportunity Zone program probably won’t be geared solely toward those types of projects, even though his firm has looked at things like affordable housing developments.

“It’s hard for Opportunity Zones to purely focus on community-type projects,” he said. “You need to have some expectation of appreciation.”

But it is projects like high-end condos that have advocates for poor and working-class areas concerned.

In New Orleans, some worry the program will fuel gentrification and displacement of residents, who are already dealing with issues of housing affordability.

“They (investors and developers) could bring mixed-income buildings with some affordable and some market-rate housing in areas where some residents are being displaced,” said Maxwell Ciardullo, policy director at the Greater New Orleans Fair Housing Action Center.

“They could also bring luxury apartments,” he said.