Running doesn’t cause arthritis. Really: A study published just last year in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery found that veteran marathoners had about half as much arthritis as their non-running counterparts. Not only that, but a more recent study published in the journal Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, shows that regular exercise actually helps prevent cartilage damage caused by arthritis by minimizing the inflammatory molecules that cause the pain and stiffness.

But the population is far from immune from the condition that’s marked by joint pain, inflammation, and a gradual wearing down of cartilage (the smooth connective tissue that protects your joints). “Runners get up to five times their body weight of force through their joints with each step,” says Florida podiatrist and podiatric surgeon Adam Perler, D.P.M. “This adds up to over two tons of accumulative pressure each day exerted on normal functioning joints.” And that’s just part of the reason we pavement pounders can wind up with an arthritis diagnosis—injury, genetics (some people are simply born with more durable cartilage), and alignment issues can also play a role in arthritis.

If you already suffer from arthritis, then you know the symptoms all too well: swollen, stiff, or painful joints first thing in the morning or after a run, limited range of motion, or even ‘locking’ or ‘catching’ in the joint. It’s only natural to look for a sustainable solution, but too often, they’re hard to come by. “Cartilage is produced by cells called chondrocytes but is not easily replaced once it is damaged,” says Perler.

Appropriately strength training the muscles around your joints, having the right shoes, and being properly aligned (if your pelvis isn’t level when you walk, or you tip during a single-leg squat, you could be overloading one side of your body putting unnecessary stress on a joint) are all good first-line defense mechanisms.

You also don’t necessarily have to give up running. Jordan Metzl, M.D., sports medicine physician at Hospital for Special Surgery, finds that many of his patients who suffer from arthritis (everything from arthritic ankles to spines) but also find a healthy way to maintain daily exercise including running, have an easier time managing the painful symptoms of arthritis. “There’s evidence that running is anti-inflammatory on the cellular level: It reduces the symptoms of osteoarthritis, aids with joint mobility, and also helps activate the muscles around joints,” he says. “All things considered, for most patients with osteoarthritis, running, in combination with a smart program that includes a gradual build in conjunction with strength training, does not have to be off-limits, and it may even help reduce symptoms.”

From there, doctors generally turn toward cortisone injections (which decrease inflammation), hyaluronic acid injections (which lubricate the joint), or a procedure called microfracture, where an orthopedic surgeon creates holes through damaged cartilage so your body can bleed into the area and patch the cartilage with scar tissue (which isn’t nearly as effective as the real stuff).

None are perfect, all are Band-Aid-like treatments that address the symptoms but not the root cause, which is why docs today are also turning patients toward some of the therapies below, hoping further science and research can bring a new wave of healing and even regeneration to runners in pain. Here are five of the latest, cutting-edge arthritis treatments.

A Portable Neuromuscular Stimulator

What it is: A souped-up knee wrap that links to an app, available at the Apple Store or Google Play.

How it works: Put the garment on and use it while doing your strength training or off-the-road gym workouts.

What it looks like now: “There’s good research that demonstrates quadricep strength can decrease pain related to knee osteoarthritis,” says Dominic King, D.O., a sports medicine and interventional orthopedic physician at the Cleveland Clinic’s Sports Health Center. “This neuromuscular stimulator can not only strengthen the quadriceps muscle, but it also records your range of motion and has a mobile phone application that can help you track your progress to ensure you’re getting the maximum benefit.”

Where it might go in the future: Sports-specific gear and apps. In the future, you might be able to change the neuromuscular stim or specifications based on your sport. There could be a runner’s app, for example, that’s programmed for your particular form of movement and potential issues, says King.

Regenerative Injectables

What they are: Three main forms of injectables aimed at helping the body self-repair — platelet-rich plasma (PRP) products (blood spun down to platelets and growth factor, important for healing); stem cell therapy (basic cells that can become almost any type of cell); and amniotic-derived tissue (from places such as amniotic fluid or umbilical cords). All can be harvested and injected into an afflicted area.

How they work: They’re aimed at helping the body self-repair. (Stem cells can mature into almost any type of specialty cells, such as those that make up bone, ligament, or cartilage.) So, the hope is that these injectables stimulate cellular healing. “I would always recommend starting with one injection. Typically, if there is no benefit in the short term, there is no need to repeat it,” says Perler. If you do notice a benefit, consider a follow-up injection a few months later, he says.

What they look like now: All therapies are experimental, typically not covered by insurance, and none are FDA-approved for arthritis, says Jonathan Finnoff, D.O., a physiatrist and sports medicine specialist at The Mayo Clinic. In theory, these therapies work—these cells do have healing properties in the body. But the research isn’t there yet (and it’s hard to know what you’re really getting in an injection). There are many unscrupulous characters out there making big claims about success rates, which is actually illegal, says Finnoff. Many stem cell injections might not even have live stem cells in them, he adds.

In a position statement, The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) also says “treatments may lack the demonstrated safety and efficacy of many traditional orthopedic therapeutics.”

The product with the most research behind it is PRP, Finnoff says. “In the majority of people, it reduces symptoms of arthritis and, in general, symptoms improve for about a year then symptoms start to come back,” he says. “Studies that do follow up MRIs haven’t shown any significant change in the volume of cartilage, though, even though we hope it’s been regenerating.” It’s important to do your research on the product being used on you and make sure you go to a reputable physician, says Perler.

Where they might go in the future: More research is needed to reveal if and how these biological tools might work, potentially revealing options where it might be possible to better isolate specific healing molecules or remove some of the factors that may inhibit tissue regeneration.

[Stay injury free on the road by getting on the mat with Yoga for Runners.]

Cartilage Replacement

What it is: Bio-engineered cartilage.

How it works: Either your own or someone else’s cartilage is implanted into the injured site.

What it looks like now: FDA-approved surgical procedures such as Matrix ACI (MACI) for cartilage defects, which surgically implants your own cartilage (grown in a lab) into the afflicted joint. Other procedures such as De Novo NT implant fresh cartilage pieces from young organ donors, which tend to be more proliferative than adult cartilage into your body. Another promising alternative is ProChondrix CR, says Perler. Harvested cartilage is specially prepared and shaped into round patches, which can then be implanted into an area where damaged cartilage has been surgically removed, he explains. “These patches have been shown to be able to further stimulate the repair and regrowth of new and viable cartilage.”

“The hope and the hype are certainly high,” says King. But there are logistical problems. “The problem is the integration of the new cartilage graft into the underlying bone. It is like a gardener importing delicate and expensive plants, which are doomed to fail unless you’re also able to import the proper soil with key nutritional ingredients that the plant can not only anchor to but thrive in,” says Perler.

“Surgeries, while promising, are also very dependent on the surgeon,” adds King. Make sure to ask questions about how many procedures they have done and what his or her background is.

Where it might go in the future: How do you get cartilage back into the body so that it adheres to the bone? That’s just one of the questions researchers will study more moving forward to hopefully increase the efficacy of these procedures.

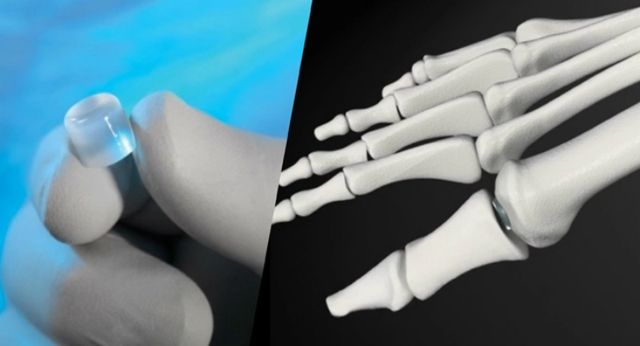

Synthetic Implants

What they are: Eraser-like implants designed to separate the bones of the joint so that surfaces don’t rub together.

How it works: Like a replacement for joint cartilage.

What they look like now: Cartiva, artificial cartilage made of materials similar to that used in contact lenses is inserted into the big toe joint to reduce pain and maintain joint motion (it’s one alternative to a fusion).

Where it might go in the future: Perhaps to more joints. Cartiva, for one, is already approved for use in the knee in Europe and The Calypso Knee System, a small device made of cobalt and chromium that can be implanted alongside your knee joint to take pressure off, is being studied at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. A clinical trial is studying the device’s ability to extend the life of the knee joint potentially delaying or even eliminating the need for knee replacement.

Coming down the pipeline…

A Disease-Modifying Injection

What it is: A shot in the knee that stops arthritis in its tracks, halting cartilage destruction.

How it works: Someday, you might be able to get the injection (dosing TBD) and stop the disease.

What it looks like now: Researchers in Toronto have honed in on a molecule called microRNA-181a-5p that’s thought to cause the inflammation and cartilage deterioration associated with osteoarthritis—and have tested a blocker that appears to stop the destruction and protect the cartilage (in pre-clinical models of osteoarthritis).

Where it might go in the future: “We have drugs that stop the pain process but no drugs that can stop the disease,” explains Mohit Kapoor, Ph.D., senior author of the study and the Director of Arthritis Research Program at the University Health Network in Toronto. “The way we envision this is if it shows further promise in terms of its ability to stop cartilage degradation and is safe, it’d be a local injection which would be given to patients with knee osteoarthritis.” Researchers are currently working on testing the safety and efficacy of a drug as well as determining the adequate dose and frequency of injections.

Cassie Shortsleeve is a skilled freelance journalist with more than a decade of experience reporting for some of the nation's largest print and digital publications, including Women's Health, Parents, What to Expect, The Washington Post, and others. She is also the founder of the digital motherhood support platform Dear Sunday Motherhood and a co-founder of the newsletter Two Truths Motherhood and the maternal rights non-profit Chamber of Mothers. She is a mom to three daughters and lives in the Boston suburbs.