Chicago flourished after the end of the Civil War; visitors and residents alike witnessed the astonishing growth of the city and surrounding environs. The population grew to nearly 300,000 by 1870, within geographic boundaries that stretched to 39th Street on the South Side. The city featured a thriving central business district and surrounding neighborhoods populated by immigrants who continually poured into the city. Lured by brisk economic growth and anticipated prosperity, thousands arrived every year to take advantage of the opportunities Chicago had to offer.

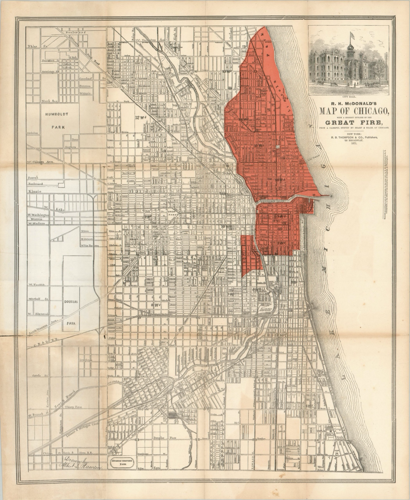

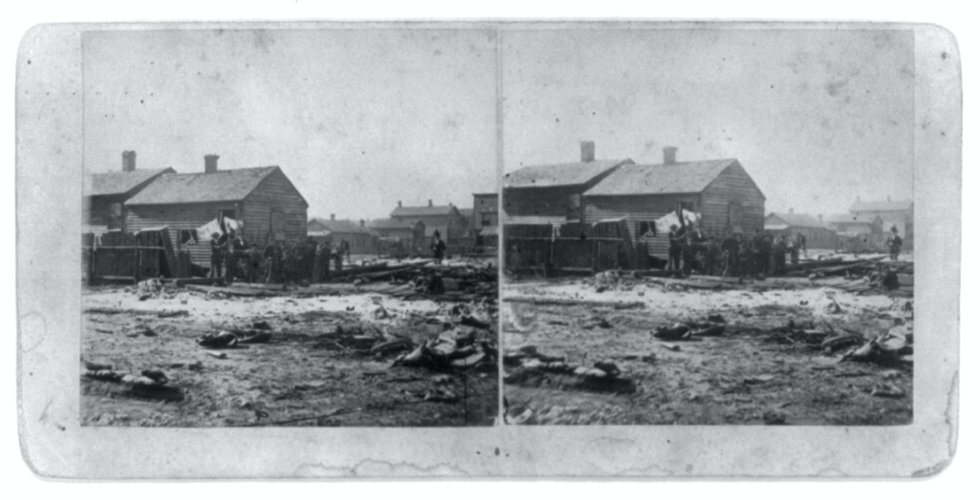

The dreams of success were interrupted on a warm October evening when, after a hot and dry summer, a fire began in Patrick and Catherine O’Leary’s barn on the Near South Side. Fueled by densely packed frame houses and wooden sidewalks, and encouraged by a strong wind from the southwest, the fire quickly spread. By the time the fire reached the central business district to the northeast it had become an inferno, and the masonry walls of commercial buildings that were supposed to be fireproof tumbled to the ground.

The city’s waterworks failed after the blaze crossed the Chicago River, which allowed the fire to continue north and destroy nearly everything in its path. After three days, rain began to fall, and the great fire died out roughly four and a half miles from the O’Leary barn, leaving the entire business district in ruins.

A stereograph of the rear of the O’Leary residence, 137 DeKoven Street, after the Great Fire of 1871.

The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 has traditionally been thought of as a turning point in the city’s history. While devastating, an era of even greater expansion began in its aftermath. Chicago’s strategic Midwestern location made certain that the city would be rebuilt, and the breadth of devastation provided the opportunity for planning on a massive scale.

That would come in time, but a different story unfolded immediately after the fire. Both downtown and in the surrounding neighborhoods, new construction looked very similar to what was built before the fire. Business owners quickly rebuilt in a manner that they knew; four-story buildings that were a hybrid of brick, stone and iron construction. It would be another decade before the earliest skyscrapers would arrive.

The fire killed 300 people, left 100,000 homeless and destroyed over 2,000 acres of land, and in 1872, the Chicago City Council mandated the use of fire-resistant materials, such as brick, in the construction of future downtown buildings. Wood buildings constructed immediately after the fire were “grandfathered” in under the law; it was not possible to expect everyone to abandon their structures and start anew with residences and businesses that were more fireproof.

Thus another fire raged in 1874, demonstrating that once a law is enacted, it often takes years for it to actually take hold. The “Second Fire of Chicago” took place on the evening of July 14, 1874, in an area adjacent to that of the great fire. The neighborhood was mostly comprised of Jewish immigrants and middle-class African-Americans. Their movement southward after the fire would come to have a major impact on the demographics of the Hyde Park neighborhood many decades later.

As the rebirth of Chicago became apparent, architects flocked to the city to participate in the rebuilding; the new business district heralded the future. Buildings were taller due to the introduction of the elevator and, within a few years, were lit with electric lights.The potential of Chicago’s business district was demonstrated with William LeBaron Jenney’s 1884 design of the Home Insurance Building and other innovative buildings that followed: H. H. Richardson’s influential Marshall Field & Company’s wholesale store (1885) and Burnham & Root’s Rookery Building with its inner courtyard enclosed by a dome of steel and glass (1888).

Although the tragedy did not alter the basic shape of the city, the fire initiated changes that transformed its “social geography,” according to Donald Miller in his book “City of the Century.” Not unlike today, Chicago exhibited a highly skewed distribution of wealth — 20 percent of the wealthiest families held 90 percent of the total assets of the city.Although differences in living standards were obvious before the fire, people of all economic and social classes lived relatively close together.

Before the fire, 14 of Chicago’s wealthiest families lived at Terrace Row, an elegant block on South Michigan Avenue. Designed by early noted architect W.W. Boyington in 1856, these homes were all were destroyed. One of the names associated with these four and a half story residences was Jonathan Young Scammon: 209 Michigan. His country residence, Fernwood Villa, was located on 59th Street in Hyde Park.

One example of residences in the heart of the pre-fire city is Terrace Row, conceived by William W. Boyington, the architect of Chicago’s beloved Water Tower and Pumping Station. Built of wood and clad in Athens marble, these distinguished homes were constructed in 1856 on South Michigan Avenue between Ida B. Wells and Van Buren. Noted Chicagoan Jonathan Young Scammon resided here at the time of the fire. In 1871 Col. John Hay wrote to the New York Tribune concerning the fire and Robert Lincoln, son of the late President:

“He (Lincoln) entered his law office about daylight on Monday morning, after the flames had attacked the building, opened the vault, and piled upon a table cloth the most valuable papers, then slung the pack over his shoulder, and escaped amid a shower of falling firebrands. He walked up Michigan Avenue with his load on his back, and stopped at the mansion of John Young Scammon (209 Michigan), where they breakfasted with a feeling of perfect security. Lincoln went home with his papers, and before noon the house of Scammon was in ruins, the last which was sacrificed by the lake side.”

Where Scammon fled after his breakfast with Lincoln is not known. However the year prior Scammon commissioned landscape architect Horace William Shaler Cleveland to design a country estate on property owned by his wife in the village of Hyde Park. Cleveland produced a graceful plan in the Romantic tradition, but the design was never realized after Scammon’s financial holdings were devastated. However the Scammons moved to the gardener’s cottage on the Hyde Park property, which they called Fernwood Villa.

While spared the flames, Hyde Park felt the fire’s effect as residential movement accelerated away from the commercial center in its aftermath. Most railroad tracks were not damaged, which permitted supplies to flow in and offered residents a way out. While some affluent Chicagoans chose to rebuild near the city center, others, like Mr. Scammon, found the residential railroad suburbs outside the city especially attractive. As the outmigration increased, wealthier residents moved with others of their class to the outlying suburbs, particularly those easily accessible and enhanced by parks and boulevards. With its bucolic lakeside attributes, ease of transportation, and planning for major parks improvements underway, the suburb of Hyde Park became a prime destination.

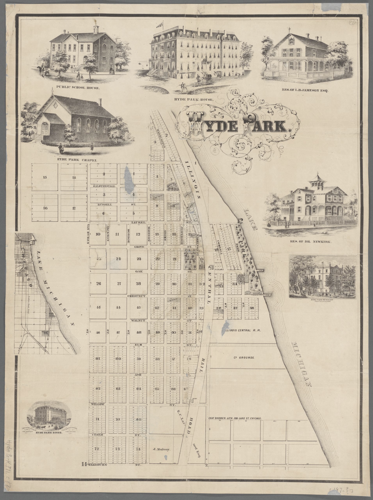

An 1870 map of the enclave of Hyde Park (pre-fire) showing the original street names, railroads, block and lot numbers and landowners' names. Also included are seven vignettes of prominent homes, businesses and institutions, primarily constructed of wood. The sketches of the residences of Dr. Adamson B. Newkirk, possibly 5313 S. Blackstone Ave., and Leonard B. Jameson are no longer standing.

Planning for the South Park system had begun years before, and a casualty of the fire was the work of Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux. The loss was a major one — without the original plans, specifications, contracts, estimates, or receipts, and having lost the atlases of the towns of Hyde Park and Lake which showed all of the subdivisions in the towns as well as ownership of land not yet subdivided, work on the parks was immediately stopped. The suspension of work continued for nearly a year, until September 1872, when landscape architect H. W. S. Cleveland (of Scammon’s Fernwood Villa) was hired and work on the parks resumed.

The original concept envisioned an eastern park adjacent to the lake and a western park connected by a drive. The plan for these areas combined elements such as shadowy, winding paths with calming and graceful elements such as broad, sunny meadows to create “a sense of mystery.” Cleveland supervised the continuation of Olmsted’s vision, and by 1875 nearly four-fifths of the western park had been improved, where 350 acres had been tilled and seeded and planted with trees. One of the first major elements completed was the “South Open Green,” a huge pastoral meadow complete with grazing sheep. The connecting drive, the Midway Plaisance, was constructed between Lake Park and South Park, and the nursery was furnishing several thousand trees each year.

These improvements to the parks with their broad boulevards, combined with the ease of the Illinois Central commute, led many to Hyde Park and Kenwood. The population expanded rapidly, quadrupling from 3,644 in 1870 to 15,724 by the end of the decade.The trend toward urbanization was immediately recognized as requiring more structure, and in 1872 the state legislature granted Hyde Park Township a village form of government. An election followed where 262 votes were cast in favor of the new form of government, with 188 cast against.

While the term “village” may imply a cozy settlement, the borders did not change, as the designation applied to the area bordered by 39th Street on the north and 138th Street on the southern boundary. The more comprehensive village form of government combined the leadership of part-time elected officials (six trustees) with the know-how of a manager (the village president). Together they were responsible for setting village policy, determining the annual budget and taxes, and outlining special assessments and condemnations in order to make much needed improvements.

During this period, the residential enclaves of Hyde Park and Kenwood at the northern end of the village developed an identity separate from the greater village of Hyde Park. Demographically, the residents there were on the wealthier end of the spectrum; an average house cost $7,000, in contrast to the southern section, where one cost $2,000. Geographically, the enclaves of Hyde Park and Kenwood were separated from the larger village by the emerging South Park system, which provided natural boundaries on both the southern and western borders.

The village trustees responsible for this huge area faced a multitude of issues and worked to provide the physical infrastructure needed to sustain the growing population. They gradually provided fire and police protection (although minimal), sanitation and sewage, streets and schools, and they outlined a structure to collect revenue to pay for all of these services. According to an 1886 Hyde Park Herald article, “Our Special Improvement System,” the law provided that the cost of any of these improvements was to “be borne by the property which will be benefitted by it.”After a petition for a particular improvement was reviewed and approved by the trustees, a department of three commissioners estimated the cost of the project and the amount property owners in the vicinity would have to contribute.

The improvements and expenses were both small and major in scope. Diseases including diphtheria, smallpox, and scarlet fever were common; therefore of prime concern were a pure supply of drinking water and an adequate sewage system. Water initially came from wells and water hawkers, and then from a pumping station at 68th Street. As the lake was used for both drinking water and the disposal of sewage, contamination made the building of the town’s waterworks of prime importance. By 1889 a new pumping station had been ambitiously constructed, extending one mile into Lake Michigan. However it was still not far enough away to prevent contamination. And although the new waterworks permitted the use of high-pressure water service at fire hydrants, at times the demand for water was so great that pressure was not adequate to raise water above the ground floor of many houses.

The 1874 fire led the major changes in fire and building codes — wood construction would no longer be permitted in Chicago. By 1876, safety measures such as metal fire escapes were mandated for residential buildings with 3 or more floors. However none of these impacted buildings in Hyde Park or Kenwood, and, according to articles in the Herald, the focus was more on equipment and less on prevention. For example, in April 1882 the Fire Commissioner made a list of suggestions as to improvements. There were 25 fires between June 1881 and March 1882, with seven fire companies handling the calls. For the future, the commissioner recommended watchmen patrol for fires, adding teams of horses, signage for fire alarm boxes and supplementing equipment of hoses, boots, rubber coats and fire hats.

In 1883 the annual message of the president (of the village of Hyde Park) boasted of 730 street lamps and “a highly efficient telephonic service” that was coordinated with the police and fire departments. By 1887 the village of Hyde Park displayed 72 miles of macadamized roads, 150 miles of wooden sidewalks, and six and a half of stone, 77 miles of water pipes, and 33 miles of sewers. Additionally, according to Jean Block, fifteen hundred gas or oil lamps lit the streets. None of this happened without considerable cost to village residents.

Although removed from many of the larger urban problems, the small community had other issues to address as it grew. Greater density and prosperity made security a concern. By the mid-1880s the Hyde Park police force included 40 men, a number that increased annually. The trustees of the village limited the sale of liquor within the community, yet taverns could be found along the commercial strip on Lake Avenue in the center of Hyde Park. All in all, the small village government had its hands full as the disparity between the village center and the outer environs of Hyde Park increased.

Sheltered by the lake on the east and the partially completed series of parks, Hyde Park and the adjacent communities were defined by their own unique characteristics that are still visible today. The center of Hyde Park was the commercial hub, and adjacent lot sizes were smaller, resulting in a more urban environment. Trains no longer refueled near 57th Street, and Woodville was renamed South Park. Kenwood featured a series of bucolic estates, and “choice lots” were advertised in the Chicago Tribune at any width by two or three hundred feet deep. Meanwhile, the broad avenues on the western border of the community developed as one of Chicago’s most fashionable places to live. By 1874, just three years after the fire, Kenwood competed with the exclusive suburbs north of the city and became known as the “Lake Forest of the south side.”

The sparks that flew from the O’Leary barn that fall evening transformed not only Chicago but the infrastructure of Hyde Park and Kenwood on a vast scale. In the 25 short years since the communities were founded, the small prairie settlements had grown rapidly and traces of the early days began to disappear. One resident wistfully commented, “Maybe lake water, and gas, and paved streets, and electric lights, and taxes had something to do with it. At any rate, the birds...and the rabbits and the flowers are all gone. And so is Hyde Park.”

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.