Timmy Couvillion knew the leak from the toppled Taylor Energy oil platform was bad. For 15 years, the platform’s damaged wells had sent up an oily sheen that sometimes stretched for miles across the Gulf of Mexico. But it wasn’t until he dropped a video camera 470 feet below the surface that it really hit him.

What the Belle Chasse marine contractor saw was not a gentle seep from the seafloor, as Taylor Energy had long maintained, but an eruption.

“It was quite the underwater volcano,” Couvillion said of the footage. “Just big globules of oil coming up by the thousands. And then we saw fish…”

Underwater footage shows fish swimming through a large volume of oil escaping from Taylor Energy drilling platform site in the Gulf of Mexico. The platform was toppled by a hurricane-triggered mudslide in 2004. The site has produced large oily sheens on the water's surface ever since. Video courtesy of the Couvillion Group.

Cutting in and out of the oily torrent were trophy-sized amberjacks that Couvillion, a former commercial fisherman and charter boat captain, would have been proud to catch.

“It made my skin crawl,” he said. “Still does, even now.”

Last April, his business, Couvillion Group, began work to halt what had become one of the largest -- and longest-running -- oil disasters in U.S. history. He started from scratch, devising a containment system that would latch on to the toppled platform, catch the oil and haul it 10 miles back to shore. As of this week, his contraption had recovered about 400,000 gallons of oil. The Coast Guard considers a release of 100,000 gallons of oil in coastal waters a “spill of national significance.”

“So we’ve basically collected four major oil spills,” Couvillion said. “And we’re going to keep on doing it.”

Timmy Couvillion

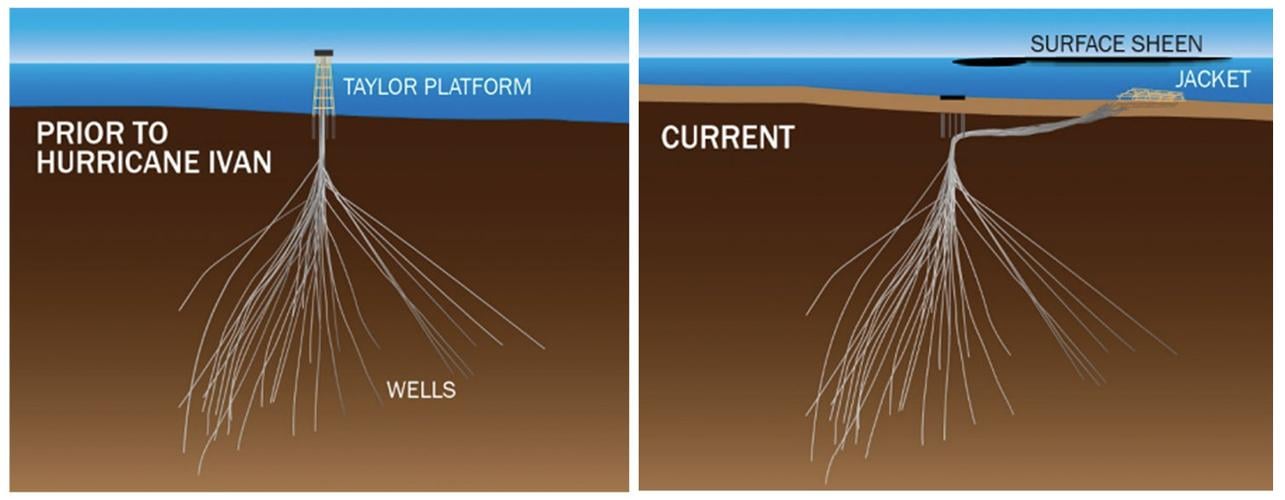

The results have been nothing short of miraculous, say the scientists and environmental groups that have for more than a decade urged the federal government to get tough on Taylor Energy, a New Orleans-based company that has done little to stop the flow of oil since its platform, known as MC-20 Saratoga, was destroyed by Hurricane Ivan on Sept. 15, 2004. The hurricane triggered an underwater mudslide that snapped the 550-foot-tall platform’s legs and buried a cluster of wells. Taylor plugged some of them and added three containment domes, but oil continued to flow.

“For years, we’ve seen the oil on the water going all the way out to the horizon,” said Scott Eustis, the science director for Healthy Gulf. “But the last few times we’ve flown out, we didn’t see any.”

Coast Guard ordered Taylor Energy to halt the leak in November 2018 after a government-commissioned study estimated the platform site was releasing between 10,500 and 29,000 gallons of oil per day. That was five to 13 times larger than a government estimate from a year before, and vastly larger than the dozen or so gallons per day estimated by scientists hired by Taylor.

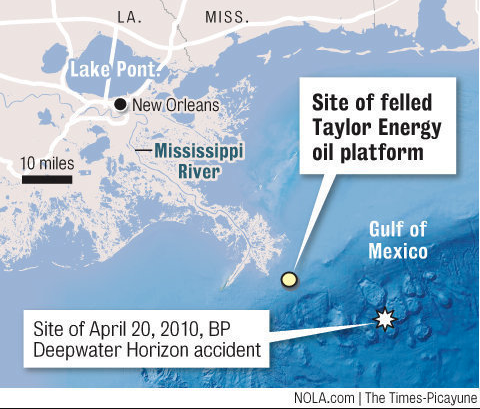

Couvillion estimates he's collecting oil at a daily rate of just over 1,000 gallons. If his device has been capturing nearly all of the oil, and the flow has been relatively constant since 2004, the total released would be a little over 6 million gallons. That could rank the Taylor Energy leak as the third- or fourth-largest oil disaster in the Gulf, behind the BP Deepwater Horizon spill in 2010 and the Ixtoc well blowout off the coast of Mexico in 1979, and on par with the hundreds of leaks from storage tanks and pipelines damaged by Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

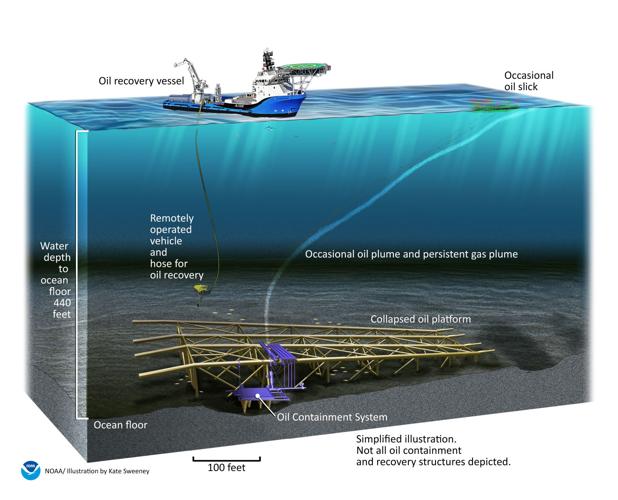

An oil containment system (pictured in purple) designed by Couvillion Group of Belle Chasse has recovered more than one million gallons of oil from the toppled Taylor Energy offshore platform site since April 2019. An oil recovery vessel connects to the containment system periodically to remove oil and take it to shore.

When Taylor challenged the 2018 cleanup order, the Coast Guard went ahead and hired the Couvillion Group to do the job. Taylor took swift legal action against Couvillion as well, claiming Couvillion Group was unqualified, had a poor understanding of the site’s "lengthy and complex history,” and could bungle the job so badly that even more oil would be released.

Couvillion, who grew up in Plaquemines Parish and studied mechanical engineering at the University of New Orleans, admits his untested idea for a containment system started as “a pipe dream.”

Once he got the contract, he and a small team sealed themselves off in an apartment and started sketching ideas.

“We pounded it out on a weekend,” he said. “I remember it was when the Saints beat the Rams, and I missed it.”

Twelve years after Hurricane Ivan destroyed a Taylor Energy Co. platform in the Gulf of Mexico, the federal government has finally started inv…

Fabricators at six locations in Louisiana built components that, once fitted together, support a 40-foot-wide steel box designed to sit over the discharge area on the seafloor. The Coast Guard didn’t want the box to touch the ground and potentially churn up oil embedded in the mud, so Couvillion figured out a way to attach the 200-ton system to the wrecked platform.

“It’s all beat up, bent and kinked, so it wasn’t easy,” he said.

The leak bubbles up into the box, and then a separator divides up the natural gas, oil and water. The oil is stored in tanks and then offloaded at a dock in Venice.

In February, Couvillion presented his progress at the Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill and Ecosystem Science conference in Tampa. The underwater video, projected on a giant screen, drew gasps. The normally staid crowd of scientists gave Couvillion a raucous round of applause.

“We’ve been pushing for this for so long,” said Ian MacDonald, a Florida State University oceanographer. “Couvillion Group has had a lot of challenges -- the engineering, the installation, the legal challenges -- but they did the job. They deserve a lot of credit for what they’ve done.”

Taylor Energy's MC-20 Saratoga oil platform standing in the Gulf of Mexico prior to Hurricane Ivan in 2004. The oil platform collapsed after the hurricane triggered an underwater mudslide.

But, MacDonald added, the containment system is not perfect -- strong currents sometimes push oil beyond its reach -- and it’s not a permanent fix. Eventually the leaking wells should be plugged, he said.

Couvillion has been readying plans and awaiting the Coast Guard’s go-ahead to do just that. Maintaining the containment system is getting increasingly costly, and his legal bills are piling up.

He estimates he’s spent about $400,000 defending his company against Taylor.

The Coast Guard allows Couvillion to offset his expenses by selling the recovered oil, but the recent crash in oil prices means he’s getting almost nothing for it.

“They’re still taking it, but they’re not paying for s--t,” he said.

This article was produced in partnership with The Times-Picayune and The Advocate, which is a member of the ProPublica Local Reporting Network.

Taylor also sued the federal government over the remaining $430 million from a $666 million trust the company was required to create to pay for oil that escaped after the platform was destroyed. Taylor, which is no longer in the oil business, says it has done all it can at the site, and that the remaining funds should be returned.

Taylor Energy was founded by Patrick Taylor, the late oilman who started and initially funded a merit-based college scholarship program for Louisianans that is now known as TOPS. He died a few weeks after the platform toppled, and all his company's oil leases and other oil and gas assets were sold four years later. The company, which declined to say what assets remain, is led by Patrick Taylor's widow, Phyllis Taylor, a prominent philanthropist and political donor.

The Taylor trust hasn't been tapped to cover Couvillion's work. Instead, the Coast Guard is drawing from the Oil Spill Liability Trust, a national fund initiated after the Exxon Valdez oil disaster and supported with fees from the oil industry. The Coast Guard may eventually try reimburse the oil spill trust with money from the Taylor trust. That'll likely spark another legal fight. Taylor maintains that its trust can be used only for well capping and other permanent fixes, and not for oil spill "response" efforts, including Couvillion's collection system.

Taylor Energy continues to question Couvillion's effectiveness. The company has cast doubt on the amounts of oil collected from the platform site, suggesting a large share of the volume may actually be water.

“Reports about containment are promising,” the company said in a statement this week. “However, Taylor Energy cannot comment on what it has not seen. Statements made to the press are no substitute for sound scientific data.”

The Coast Guard vouches for Couvillion. In a statement, Capt. Kristi Luttrell, the New Orleans sector commander, said "the containment system has been very effective, with an average daily collection rate of 1,000 to 1,300 gallons." The more than 375,000 gallons the Coast Guard has verified is of a “re-sellable” grade, composed of less than 1% water.

The company remains dubious.

“Unfortunately, the Coast Guard has refused Taylor Energy’s multiple requests for data to verify its claims about how much oil is being collected from the seafloor; nor has the Coast Guard provided any explanation for its campaign of concealment,” the company said.

An oily sheen appears on the water's surface just before the Couvillion Group installed an underwater oil containment system at the site of the damaged Taylor Energy drilling platform.

Taylor also disputes the release volumes cited by the Coast Guard, and the cause of the sheens.

Christopher Reddy, a marine scientist hired by Taylor, said the sheens are likely produced by oil released from seafloor sediment rather than an active leak from a well. The seafloor was “heavily contaminated” with oil when the platform was destroyed, and relatively small quantities of the oil bubbles up to the water's surface, Reddy said. He cautioned that any restoration or cleanup work at the site could release a large quantity of oil.

Couvillion shrugs at Taylor’s concerns. The proof of his success is easy to see. It’s in the sheen-free water and the tank after tank of oil he hauls away.

“It is just truly unbelievable that this was allowed to happen for so long,” he said. “I guess it’s about having a can-do vs. a cannot-do attitude. We went with can-do. And we rocked it.”

The Dutch have a new lesson: Building bigger, better infrastructure won’t be enough to overcome the threats posed by changing climate.