Natural products are the origin of many of today’s beauty products and medicines, with plant, mineral and animal product extracts analysed and then often re-made, or improved upon, in the lab.

Today we have one story about new discoveries from old recipes, and another about what can happen when this kind of chemistry goes wrong.

Photo: MAKI

Follow Our Changing World on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, iHeartRADIO, Google Podcasts, RadioPublic or wherever you listen to your podcasts.

The Beautiful Chemistry Project

When art historian Associate Professor Erin Griffey was invited to give a public talk on her research into Renaissance beauty culture, she thought some show and tell would be the way to go. Linking up with some of her University of Auckland colleagues in the chemistry department she pulled out a few old recipes and they started making a batch of 15th-century beauty products.

That was the birth of the Beautiful Chemistry Project - an investigation into Renaissance beauty recipes to discover the secrets they might hold.

Dr. Michel Nieuwoudt and Associate Professor Erin Griffey at the Beautiful Chemistry lab space. Photo: RNZ

Griffey’s extensive research and cataloguing of Renaissance texts on the subject has provided a database of thousands of beauty recipes, including ingredients from the mundane, to the bizarre and sometimes even dangerous.

Since Senior Research Fellow Dr Michel Nieuwoudt got on board she has helped to support summer students in their investigations of some of the ‘stickier’ recipes. Those that, according to Erin’s database, resurfaced numerous times across the decades and in different countries.

Using chemical and functional analysis the team are figuring out how these recipes work, and if there are compounds in these old beauty products that have been overlooked by today’s cosmetics.

Investigating the dangers of AMB-FUBINACA

Between 2017 and 2019, the synthetic cannabinoid AMB-FUBINACA was Aotearoa New Zealand’s deadliest illicit drug.

Across those two years, it is thought to be related to at least 58 deaths, though may have contributed to more than 70.

Cannabinoids are compounds found in the cannabis plant that are able to activate cannabinoid or CB receptors in our bodies. This is because we have our own endocannabinoid system – cannabinoids we make ourselves that bind to these receptors.

Scientists haven’t fully worked out the complex story of this endocannabinoid system but it does seem to play roles in some important functions including mood, memory, pain, immunity and stress. So researchers began the process of creating synthetic versions of the plant cannabinoids (phytocannabinoids) in the lab to investigate their potential medicinal benefits.

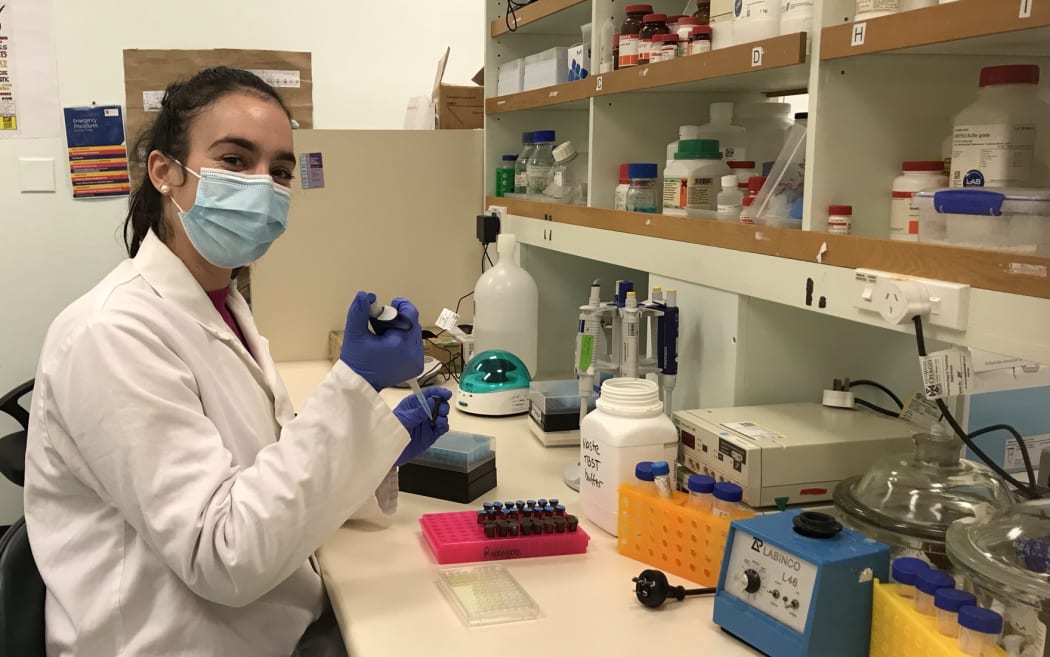

Lucy Thomsen prepares an experiment in the lab. Photo: RNZ

The major players are Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). THC is the cannabinoid responsible for the ‘high’ – the psychoactive effects of using cannabis. It does this by activating CB1 receptors in the brain.

AMB-FUBINACA is 75 – 80 times more potent than THC. Originally developed by the pharmaceutical company Pfizer as part of their drug discovery pipeline, it has since been co-opted by those in the illicit drug market.

However, the exact details as to why AMB-FUBINACA is so dangerous aren’t clear. This is what Lucy Thomsen, a toxicology PhD student at the University of Otago, is delving into for her research.