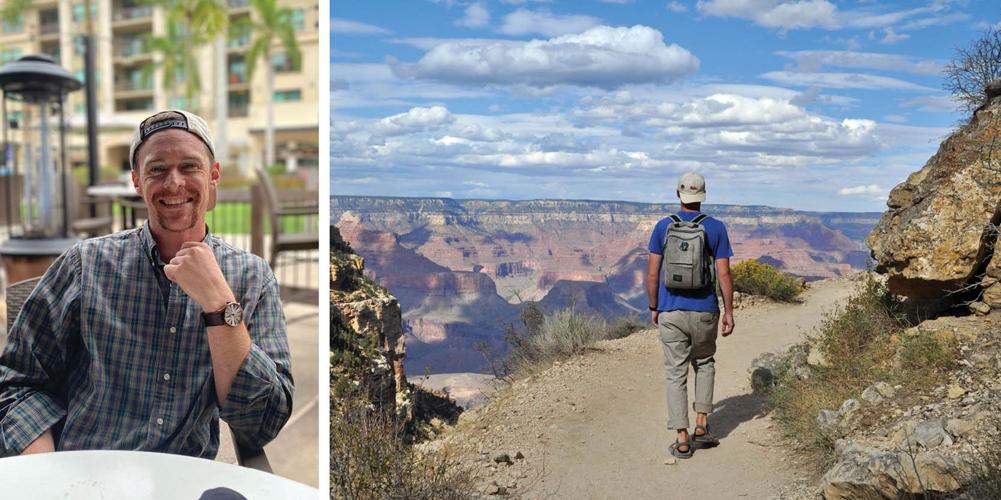

Tyler Smith

On April 7, Tyler Smith graduated from a 10-week addiction treatment program in Athens, Tenn. His family traveled from Knoxville for the occasion and felt optimistic that, this time, his recovery might last. At 31 years old, he told his mother Danita McCartney that he was ready to be done with the cycle that had shaped his life for more than a decade.

Like many teens, Tyler partied in high school, drinking beer and smoking weed on occasion. But the beast got its claws in him toward the end of his senior year, when a co-worker at a restaurant — a work environment where drugs are often found about as easily as any other ingredient — showed him how to crush an OxyContin and snort it. He spent the next 12 years in and out of the clutches of addiction. Danita would cling to hope where she could find it. As a young boy, Tyler had always been deathly afraid of needles — perhaps that would at least keep him from shooting up. It didn’t.

But Danita says there were wonderful seasons of sobriety. Tyler loved the Grateful Dead and the mountains. Despite it being where he was introduced to hard drugs, the restaurant industry had made him into an excellent cook, and he delighted in taking over the kitchen at holidays to make a meal for the whole family.

In between those seasons, Tyler wandered, living for short stints in various places around the country. When he struggled, he had the support of his family, and his mother says he found great treatment through urban rescue missions similar to the one where she works in Knoxville. He spent time in recovery programs in Alabama, Indiana and Florida before moving to Nashville, where he rekindled a relationship with a young woman he’d known in high school. He found a job at a downtown restaurant — there, again, he found drugs. In January of this year, he survived an overdose after his girlfriend was able to revive him. That prompted his family to send him to the program in Athens, where he stayed for more than two months.

After he graduated from the program, Tyler returned to Nashville and got a job at an irrigation company, deciding to stay away from the kitchens where he’d been unable to resist substances. He talked on the phone with his mother frequently, never failing to end a conversation by telling her he loved her. But on the morning of Tuesday, April 14, Danita received the phone call she’d been expecting for years but could never prepare for. Tyler’s girlfriend had found him dead in the living room. A toxicology report later revealed what was in his system: meth and fentanyl, the latter a synthetic opioid that can be 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine and lethal in doses as small as 2 milligrams.

Tyler’s death inducted his family into a growing, grieving community — those who have lost loved ones to a raging epidemic of drug deaths, the majority of which have been caused by fentanyl. It’s the other epidemic, one that has been largely overshadowed by the global COVID-19 pandemic. But in Nashville, it’s claimed almost as many lives. From March 20, 2020 — the day of the first confirmed COVID-19 death in Nashville — to Oct. 16, 2021, the city reported 1,113 deaths from the virus. In that same time period, 1,070 suspected drug deaths have occurred in Nashville. That figure includes residents, non-residents and people whose status is unknown. According to the Metro Public Health Department, residents have accounted for around 70 percent of all drug deaths in Davidson County this year.

The coronavirus pandemic has made us all terribly familiar with the notion of the so-called curve. Fentanyl deaths are still rising, and this curve is showing no signs of flattening.

It was 2017 when Candice Sexton started noticing more bodies coming into the morgue with fentanyl in them. By then she’d been investigating the dead and their bodies for around 20 years. A professional field that is morbidly repulsive to many came to her attention by way of the long-running HBO documentary series Autopsy hosted by Dr. Michael Baden.

“I watched that show, and when I did, I just knew that’s what I wanted to do,” Sexton tells the Scene.

This was back before shows like CSI popularized forensics — for better or worse — and it was a bit easier for someone with an interest in death investigations to get in the morgue door. Sexton looked up her local medical examiner in East Tennessee, and two weeks later, she says, “I was up to my elbows in my first body.”

The work felt deeply serious, almost sacred to her. She still remembers the name of that first person, a woman whose family had questions answered by the autopsy Sexton participated in. It’s that role that has buoyed her through more than two decades of traumatic work.

“How I cope with it is, I’m that final voice,” she says. “And if I don’t speak for them, who does?”

Sexton worked as a forensic technician — the person who assists a doctor during autopsies — for years, spending time at the Georgia Bureau of Investigation as well as in Phoenix before returning to East Tennessee. Around 2010, she came to Nashville to work as an investigator — responding to scenes of unnatural deaths — at the Middle Tennessee Regional Forensic Center, which serves as the medical examiner’s office for Davidson County and provides autopsy services for 52 counties. In 2016, Sexton became the office’s director of investigations. Even before she became director, she’d made a habit of tracking the trends in death, particularly the kind of drug deaths that the office was seeing. It was a practice she started after a week in 2014 during which a streak of cocaine-related deaths caught her attention.

In 2017, she noted that more suspected drug deaths were coming in. But toxicology reports can take four to eight weeks, so it took some time for the pattern to emerge. More and more of the people she was seeing had died due to fentanyl. She started tracking them and sounding the alarm.

“Everybody I could get to listen to me,” she says. “I mean, law enforcement would call in a death and it’s like, ‘Hey, look, we’re seeing this, what are you seeing?’ ”

At first, fentanyl was mostly found in heroin, which had been cut with fentanyl to extend its supply. Fentanyl is cheaper and more potent, making it the perfect ingredient for a dealer looking to maximize their profits. But then it started showing up in cocaine, and then meth. Now, Sexton says, she sees it in all of those as well as in counterfeit but visibly indistinguishable versions of prescription pills like OxyContin, Percocet and Xanax.

At a press conference last month about the increase in counterfeit pills on the street, Tennessee Bureau of Investigation Director David Rausch said that half of the “oxycodone” tablets the agency receives as evidence do not contain oxycodone at all, instead only fentanyl.

“Let me be clear,” said Rausch. “If you’re buying pills on the street in our state, you’re gambling with your life.”

As Sexton speaks, sitting in her office down the hall from the morgue, she pulls out four stacks of paper, setting them down on her desk one after another, each one larger than the one preceding it. These are her records of the fentanyl deaths her office has seen in 2018, 2019, 2020 and so far in 2021.

The number of fentanyl deaths her office has seen almost certainly represents an undercount. Although the office services 52 counties in and around Middle Tennessee, the Middle Tennessee Regional Forensic Center doesn’t end up performing an autopsy on every body from those jurisdictions. In any case, the surge is staggering. In 2017, the office recorded 180 fentanyl deaths. In 2020, it handled 1,023 — a 468 percent increase in the span of four years. This year’s deaths are on track to outpace last year’s.

On the day of our visit, the office has handled 20 death cases; 10 of those are suspected drug deaths.

Sexton’s staff, made up mostly of women (and one new male hire), is overwhelmed, as are the facilities. Down the hall, two large refrigerated rooms are full of bodies. Outside sits a refrigerated mass disaster truck. It’s intended for mass casualty events, and the ubiquity of fentanyl has turned out to be one. Another refrigerated trailer from the Federal Emergency Management Agency is on site too. It was meant to help the facility handle the strain of the coronavirus pandemic. But many COVID deaths haven’t required a medical examiner, as the deceased were under the care of a physician when they died. The strain has come from the rapid increase in drug deaths, Sexton says. The facility got permission to keep the refrigerated truck, and it’s now nearly a third full. The bodies are white, black and brown — Metro Public Health Department officials say the scourge is affecting all races, generally in proportion with the population.

“I lay awake at night and go, ‘What can I do?’ ” Sexton says. “I’m just such a tiny, small part of this puzzle. My team? So overworked. We’re constantly going out to these scenes, and it’s just overwhelming for us.”

Left: Trevor Henderson from the Metro Overdose Response Program holds narcan

Right: Josh love, an epidemiologist in the Metro Overdose Response Program

Deep inside the Lentz Public Health Center on Charlotte Avenue, there is a small office labeled Metro Overdose Response Program. There, five people — led by director Trevor Henderson — are trying to track and fight the escalating crisis. Their resources are meager, although they represent a significant increase from when Henderson got the job several years ago.

In 2017, with the opioid overdose crisis still ravaging communities across the country, the Metro Public Health Department created a position for someone who would focus solely on overdose deaths. It was one position with no budget, and it went to Henderson. Originally from Northern Ireland, he was familiar with the prospect of doing community work with life-or-death stakes. In his home country, he did harm-reduction work with at-risk youth and worked to impress upon the paramilitary groups who were running drugs the ways in which substance abuse was destroying lives and communities. He also spent time working with people addicted to heroin in Hong Kong in the late 1990s. When he moved to Nashville around 2003, he had a girlfriend — now his wife — and some friends, but not much of an idea about what he would do for a living. Appropriately, the Rev. Charlie Strobel took him in, and Henderson worked at Room In The Inn while he went through the immigration process. After that he spent some time working with Catholic Charities before ending up at the health department.

When he took the new job focusing on overdose deaths in 2017, Henderson had four basic if ambitious mandates: work on collecting and analyzing data to truly understand the scope of the crisis; expand the department’s partnerships with community organizations; find ways for the department to get involved in harm reduction; and work to reduce overdoses.

It was around that same time that Candice Sexton had started sounding the alarm from her perch at the medical examiner’s office, and Henderson was one of the people who heard it. They started collaborating and sharing data. That led to more data sharing with agencies like Emergency Medical Services. More recently, a U.S. Department of Justice grant allowed the Metro health department to hire an epidemiologist, Josh Love, for Henderson’s team. Love had spent time in the Peace Corps and had a background in public health emergency work and using data to inform action in the community. Love, Henderson says, has built a data surveillance system for drug deaths from the ground up — one that has attracted the attention of other states looking to create something similar.

On a recent morning in their office, Henderson and Love walk the Scene through the data the system has collected, sketching a fairly detailed picture of a crisis in progress. As Love notes, it’s the other ongoing federal public health emergency, along with COVID-19. A proper surveillance system — akin to the ones used by public health officials to track the pandemic — has allowed them to better understand the nature of the crisis, as well as its scope, which informs how we might best respond to it.

“The nature of the crisis has just really changed,” Henderson tells the Scene during a separate conversation. “We are not dealing with the opioid crisis that I started out working on. We can really see in the data where prescription pills drop off in our overdose deaths in around 2018, and at the same time you can see illicit fentanyl taking off in the community.”

Like Sexton, they’ve seen fentanyl move from heroin to the whole gamut of drugs that can be found on the street and in the rise of counterfeit pills. They’ve also seen the rise of fentanyl analogs, modified versions of fentanyl that in some cases are even more potent. Their data shows how fentanyl has become the primary cause of drug deaths in Nashville. In 2016, about 1 in 5 drug deaths was caused by fentanyl. By 2020, it was implicated in three-fourths of all Nashville drug deaths.

The data also shows in black-and-white numbers about how short it’s cutting the lives it claims. A commonly used statistic in public health is years of potential life lost — that is, the person’s reasonable life expectancy minus the age at which they died. In Nashville, they calculate that the people dying from fentanyl would have had an average of 30 more years to live.

Henderson elaborates on this statistic: think of the impact of 30 years on families, communities, workplaces. Paradoxically, the statistic indicates a loss that is incalculable.

Drug deaths and near-deaths are now a constant hum in the background of daily life in Nashville — one that’s been getting louder every year. In 2016, Metro EMS responded to around 3,000 suspected overdose calls. In 2020, through several waves of the pandemic, they responded to around 6,000. In 2016, the city recorded 300 drug deaths; in 2020, there were 620, and all signs indicate there will be more this year than last. Currently, EMS responds to around 20 suspected overdose calls a day, and the city is averaging about two drug deaths every day.

The team has no idea when drug deaths will plateau. And one of the alarming effects of the rise of counterfeit pills is that it expands the likely universe of people who may come into contact with a lethal dose of fentanyl. Every person who dies a drug-related death matters, but as a matter of blunt mathematics, there are many people who wouldn’t do heroin but might take a couple Percocets from a trusted friend — pills that could turn out to be pressed fentanyl instead.

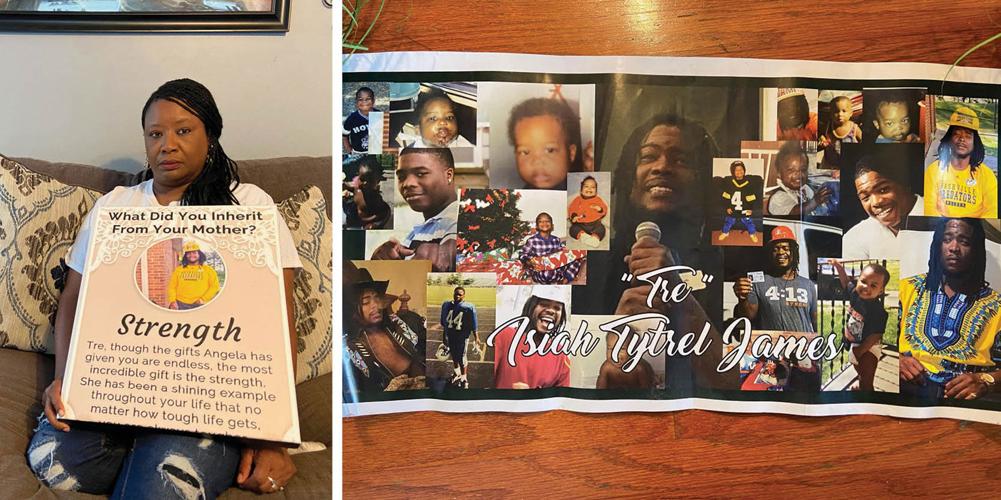

That’s what happened to Tre James, a 27-year-old who was staying at his mother’s house in Murfreesboro in August 2019 when he took what he thought were two pain pills. His mother Angela James walked into his room hours later, believing he’d been asleep.

Angela James

“When I turned the light on, the flip of that light changed my life,” she tells the Scene. After Tre’s death, Angela started a foundation in his name focused on helping youth in the community.

The small team at the Metro health department can’t single-handedly stop the supply of drugs or the demand for them, much less the rise of a terrifyingly lethal substance like fentanyl. It’s like a game of Whac-A-Mole where every mole can kill. For now, they’re trying to track the crisis and respond in ways that might keep some people from dying.

One way they do that is by alerting the public to “overdose spikes” in the community using a text notification pilot program rolled out in June. It’s not dissimilar from warning the public about a viral outbreak. The idea is to reach at-risk people or those who might be around them — that is, just about everyone — so they can take precautions against potential drug deaths. On Oct. 4, the department sent out an alert after EMS saw its largest spike in suspected overdose calls since Metro health started keeping track in 2016. The department is under no illusions about abstinence — the alerts urge residents to check in on loved ones and not to use alone.

The Metro health team goes even further. Using a program called ODMAP, which has been implemented in cities across the country, they get near real-time surveillance data about suspected overdose activity. From their office they can pinpoint so-called overdose outbreaks on a map of Nashville. By now they know certain hot spots, although they declined to release them publicly to avoid stigmatizing particular neighborhoods. When outbreaks occur, they’ll work with community partners to spread the word and try to get area residents and businesses to carry naloxone, commonly known by the brand name Narcan — a medicine that can rapidly reverse an opioid overdose. They also urge anyone using drugs to reduce their dose and, if possible, use fentanyl test strips. The last recommendation is complicated by the fact that, under current state law, test strips are considered drug paraphernalia. Police and prosecutors in Nashville aren’t charging people for possessing them, but Henderson says the law has still made it more complicated for local agencies to obtain them.

In recent years, the Metro health team has been working more closely with the Metro Nashville Police Department. Henderson says it’s taken time for the relationship to develop but that there has been a notable change in the MNPD’s tone and approach to the drug crisis since the change in leadership a year ago, when John Drake replaced longtime Chief Steve Anderson.

Throughout multiple conversations about the crisis, Henderson emphasizes the need for acute and chronic responses. Reducing drug deaths will mean taking immediate harm-reduction steps while also creating better links between the agencies fighting the crisis and treatment resources for people struggling with addiction. The emergency departments that treat people do great work, he says, but they aren’t social workers. One of Henderson’s projects right now is building better and quicker connections between emergency departments and treatment options.

Sitting in the team’s office with ODMAP pulled up on a television screen, he and Love isolate cases in which EMS responders had to use multiple doses of naloxone on someone, represented by purple dots on the map. Right now they’re non-fatal cases, but Henderson knows they’re not likely to stay that way.

“What I don’t want is, you know, that purple dot up there, they went to the emergency department, somebody saw them in the emergency department, stabilized them and sent them back out,” he says. “They’ve gone back to the same community, the same stressors, the same job, the same dealer. They’re still exposed, they’re at a much higher risk of overdosing again once they’ve overdosed once.”

When a suspected drug death occurs, the case is assigned to a police detective whose primary task is to piece together the person’s last 24 hours. The goal is to determine where the substance that killed them came from.

On an October morning at the Davidson County District Attorney’s offices, the Scene sits down with one of those detectives — a member of the MNPD’s Specialized Investigations Division who spoke on the condition of anonymity — and Assistant District Attorney Mindy Vinecore, who’s leading the office’s partnership with the police department on drug investigations. The two agencies constantly work together for obvious reasons, but this specific collaboration is relatively new as it’s focused on making prosecutable cases out of drug overdoses.

From their separate vantages, Vinecore and the detective have witnessed the same mutations in the world of street drugs as their counterparts in public health and forensics. Five or six years ago, Vinecore says, it was common for dealers to use ingredients from a vitamin store to cut their product. Now they’re using fentanyl. It’s cheaper, readily available and, of course, incredibly potent. The detective says with evident surprise that some dealers have seemingly made accommodations for that new level of risk.

“We’ve even seen where sometimes the narcotics dealers will distribute Narcan to their customers,” he says.

But most transactions aren’t that way, and a recent change in state law has made it easier for prosecutors to come after people who sell or distribute drugs. Tennessee already had a so-called death by distribution or drug-induced homicide law, which allows a person to be charged with second-degree murder if they sell or provide drugs to someone who dies from the substance. In 2018, the legislature explicitly added fentanyl to the law. Prosecutions have ramped up in the years since.

The detective and Vinecore both say family involvement is often the most critical part when it comes to making a case. The families that the Scene spoke to were undoubtedly in favor of such prosecutions.

Tanja Jacobs expresses frustration with the pervasive use of the word “overdose” in media and by public officials, because it conjures up an image of someone on a bender or a person who is addicted and pushing their limit. Her son, Romello Marchman, died on Memorial Day 2020 when — struggling with the stress of work and depression exacerbated by the pandemic — he used what he thought was cocaine. It was fentanyl. When talking about what happened to him, she prefers the words “poisoning” or “murder.”

“A lot of our kids weren’t addicts,” she says. “They just got a drug that they didn’t ask for and they died from it.”

Even those who are fighting addiction in many cases likely wouldn’t have died if fentanyl hadn’t been in the substance they were using. Someone has been charged in connection to Tyler Smith’s death, and his mother Danita is fully supportive of the prosecution. She notes with sympathy that many people who sell drugs may well need help themselves, but rejects the idea that people who are addicted to drugs should effectively be blamed for their own deaths in such cases.

“Tyler didn’t order up drugs that night with the intention of dying,” she says. “Just like, I think, with someone who stays in an abusive relationship and is maybe murdered at the hands of an abuser. You don’t criticize her for staying — you go after the person who did it to her.”

As in much of the criminal justice system, the idea of deterrence is at the heart of drug-induced homicide prosecutions.

“What we’re hopeful [about] is that if we’re able to, you know, prosecute these cases, maybe the dealers get a little more careful about what they’re cutting in,” Vinecore says. “If they see somebody getting sentenced on a second-degree or some kind of murder charge, maybe that, you know, is more of a deterrent. ‘I’m not going to cut all of this drug in it.’ ”

She suggests the office is mindful of the distinction between someone who is addicted themselves, selling to support the habit, and the hardened drug dealer in the public imagination. Vinecore notes that the law doesn’t draw such a line, but says prosecutors take it into account when it comes to sentencing.

But there is good reason to be skeptical about the outcomes of laws like Tennessee’s and prosecutions of this sort. Fentanyl, which is often though not exclusively made in China and brought to the United States through Mexico, has radically changed the drug trade. It’s cheap and thus massively profitable. Drug-induced-homicide laws also often miss the target many people might have in mind. A 2018 New York Times investigation detailed the way that, far from kingpins, it was friends, family members and fellow users who ended up charged across the country for sharing drugs.

There’s also a strong body of evidence suggesting that the threat of prison doesn’t deter drug crimes. A 2017 Pew analysis “found no statistically significant relationship between states’ drug offender imprisonment rates and three measures of drug problems: rates of illicit use, overdose deaths, and arrests.”

Like their counterparts, the detective and the prosecutor are overwhelmed by the scale and human toll of the problem. The detective’s compassion for people who have lost loved ones to fentanyl and his drive to slow the flow of the substance that’s killing them are palpable when he speaks. But he acknowledges that he and his colleagues are trying to block a fire hose with their bare hands.

In June, the MNPD and agents from the Drug Enforcement Agency found 15 pounds of fentanyl, along with other drugs, at a home on Luton Street near Dickerson Pike. In August, they seized more than 50 pounds of a white powder presumed to be fentanyl — enough to theoretically kill 11 million people — from a tractor-trailer on I-40 in Nashville. That’s not a drug seizure so much as it’s the discovery of a nuclear arsenal. And yet, while these seizures represent victories for law enforcement, they also stand as evidence of the massive failure of America’s War on Drugs.

And the detective readily acknowledges that this is just a fraction of the fentanyl coming into the city.

Comparison of a U.S. penny to a potentially lethal dose of fentanyl

In the corner of a Mexican restaurant in Old Hickory one recent evening, a man sits over a margarita with a Scene reporter discussing drug culture, harm-reduction efforts and the rising death toll of fentanyl in Nashville. For him, it’s no abstract issue.

He’s lost seven people he knows to drug deaths this year, he says — three of them in Nashville in the past few months. He uses drugs too — cocaine every now and then, psychedelics, pot. He favors the legalization of drugs and the normalization of safe drug use, but he’s speaking on the condition of anonymity since those aren’t a reality yet.

Coming up in the punk scene and around other subcultures, he was introduced to drugs but also to people who took harm reduction seriously. Now in his early 30s, he’s tried to spread those practices to people in his social and professional circles. He’s advocated for people in the bars where he’s worked to carry Narcan and thinks the kind of training course he’s taken in how to administer the medicine should be required in those sorts of workplaces. Some people react incredulously, he says, noting that they don’t do drugs.

“You definitely have friends who do,” he says. “We all do.”

He’s also tried to spread fentanyl test strips, but they’re expensive and can be hard to come by. He uses them sometimes to test drugs and has had drugs he would have used test positive for fentanyl. It scares him, he says, but he also confesses to being “reckless” on occasion.

“I’m definitely not always the safest person, but I try to be,” he says. “I usually don’t do random drugs. I try to get them from people [I know], but that’s still not safe, you know?”

Earlier this year, Oregon became the first state in the U.S. to decriminalize small amounts of most hard drugs. Policies like that, he believes, help destigmatize drug use and give governments more space to pursue policies that will keep people safe.

“I started doing harm reduction, but by no means am I like, ‘Don’t do drugs,’ ” he says. “I think smart drug use is better than being like ‘no drugs’ or whatever. I feel like educating people to do drugs smarter is the future. You can’t tell people no — they’re gonna do it. You can’t shame people — they’re gonna do it. They’re just gonna do it without telling you, and you’re gonna alienate them.”