Traveling salesman Elon Musk has found another buyer for one of his tunnels. Fort Lauderdale Mayor Dean Trantalis said on Tuesday that the Florida city had “formally accepted” a proposal from Musk’s side-project the Boring Company to build an “underground transit system” from downtown to the oceanfront beaches a couple miles away.

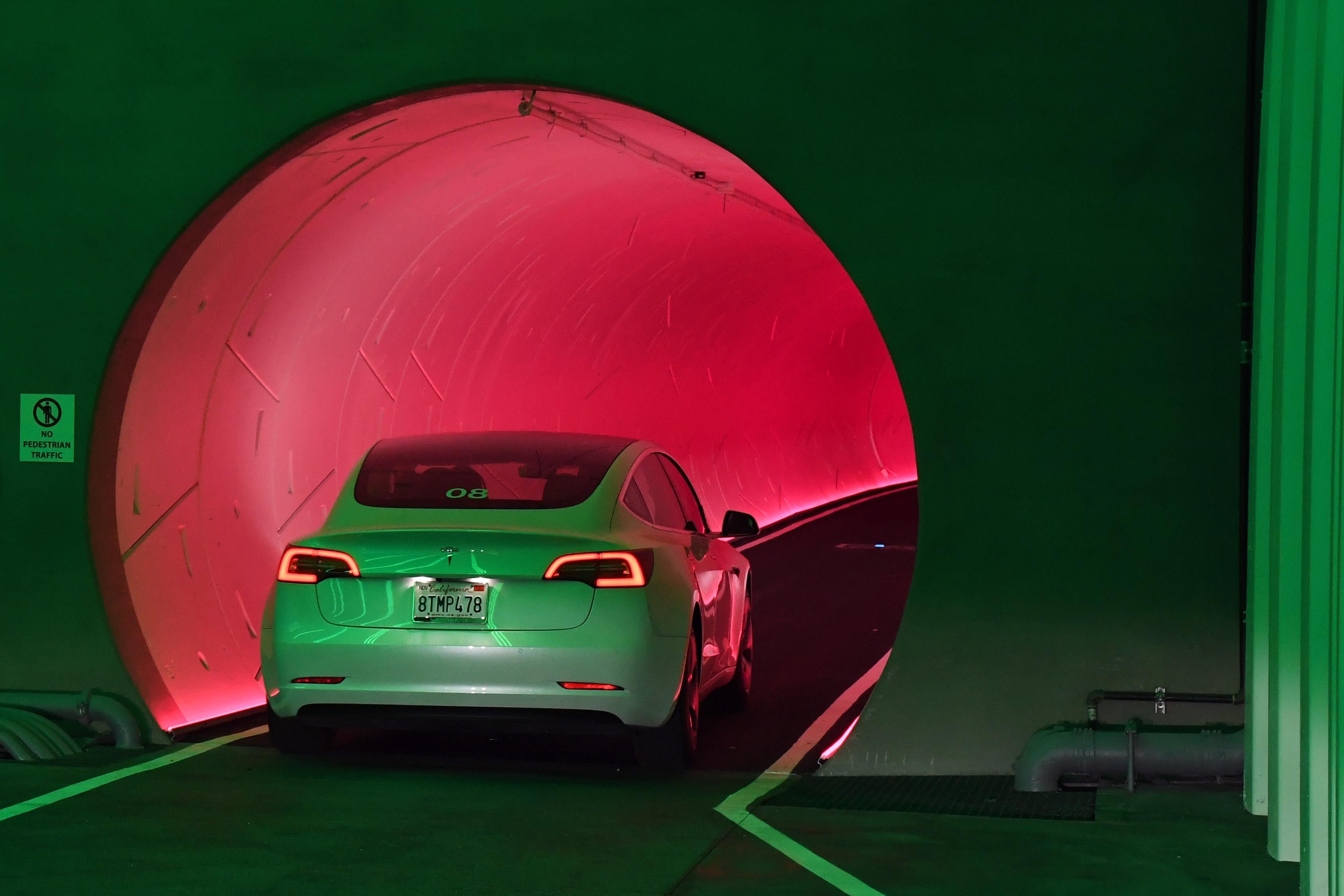

My opinion about these tunnel projects has not changed since Musk invited reporters into his test tube in Hawthorne, California, two and a half years ago: They combine the constraints of transit with the inefficiencies of the automobile. In the time since, the Boring Company actually developed a taxpayer-funded system for the convention center in Las Vegas, and I still don’t see the point of a circuit that combines low ridership, low speed, and high cost.

But apparently that separates me from the bulk of America’s elected officials, who continue to gravitate toward Musk’s ideas like moths to a Boring Company-branded flamethrower. It’s as if Musk himself is doing the digging, rocketing around the country underground like a supersonic mole to pop up in a new city each week with his table of wares.

Much has been promised and little has been built. The Baltimore-Washington “loop,” promising rapid trips in Tesla’s own cars running on tracks through a tunnel, got the furthest: The Boring Company bought property in D.C. and the state of Maryland drafted an environment impact statement. Then the Boring Company threw in the towel, removing the project from its website and showing no interest to the federal agency reviewing the plan.

Musk said he would construct a privately funded express service to get travelers from Chicago O’Hare Airport to the Loop in 12 minutes, on skates traveling at speeds up to 150 miles per hour. That idea vanished when Mayor Rahm Emanuel left office.

In Los Angeles, Musk has promised not one, not two, but three tunnel ideas for public use, with no signs of delivery on the horizon.

The current raft of Boring Company projects includes an airport tunnel in San Bernardino, a citywide “loop” in Las Vegas, and now tunnels in Miami and Fort Lauderdale. If Musk can get stakes in the ground in Florida, he would double the state’s number of tunnels. Literally, there are only two tunnels in the low-lying Sunshine State.

If it weren’t for Musk’s imperial pronouncements and the obsequious news coverage that follows his every move, this string of failed endeavors would be unremarkable: Infrastructure takes time, and urban history is littered with unrealized schemes.

But there’s a lesson in here about a particular strain of Musk’s hubris. What is impeding the creation of new infrastructure in this country is not a lack of state-of-the-art digging technology, which is The Boring Company’s purported specialty. Instead, it’s a range of cumbersome practices that not even Musk can disrupt, such as lawsuits, regulations, environmental reviews, and overlapping jurisdictions. On the contrary, Musk’s idiosyncratic visions (tunnels full of cars, but way smaller than normal tunnels, and the cars drive themselves but not really, and occasionally burst into flames that cannot be extinguished) seem to leave regulators particularly wary.

Musk has excelled in step one of getting things done in the US, which is seizing the attention of elected officials. But if that and that alone is all his company does, then it’s no wonder Musk’s tunnels so often end in the same place as many better ideas: nowhere.