Hinesville — The drill instructor burst out of the classroom door carrying a student by his neck. The taller and beefier adult had the boy so outsized, the chokehold from behind lifted him up on his toes with his head bent back.

“What are you going to do now?” the uniformed man barked. Then the student passed out, with a teacher stepping in to catch him before his head could hit the ground.

That account from last April, based on witness statements in internal records, is among dozens raising questions about safety inside Fort Stewart's Youth Challenge Academy for 16- to 18-year-old Georgia youth.

The state and federally funded program in this rural town near Savannah bills itself as a place where difficult teens at risk of dropping out of school can finish their education in an atmosphere of military discipline. The Georgia National Guard runs the academy and high school students from throughout the state apply to attend.

But an investigation by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution found that some of the academy’s uniform-clad security staffers — most former military themselves — used their positions to physically abuse their teenage cadets, some of whom were in such fragile mental states they attempted to escape, harm themselves or commit suicide.

A former cadet from the Savannah area, who spent a session there in 2018, said cadre often used brute force against students, who lashed out at staff and each other under the stress of being separated from their families. She described mold on the walls and showers, broken bed frames and rats and insects crawling through the barracks.

"We were kids treated like animals," Tabitha Olsen, 18, told the AJC in a text message. "I understand how they liked to call themselves a military school and that it was supposed to be challenging, but I went through basic training for the Navy and it was nothing like the treatment that school put me under."

Public documents and former staffers describe disadvantaged children being choked and slammed to the ground by adults who faced little or no consequences. In another documented case, a sergeant reportedly placed a teenage boy in a chokehold — a practice banned in many police departments — and wrestled him to the ground because he was talking during quiet time and refused to leave his barracks.

“Why is my cadre allowed to choke me?” the teen would later ask one of his teachers.

Academy military staff, known as cadre, are supposed to de-escalate encounters with students who are fighting, upset or experiencing a crisis. The program uses nonviolent techniques developed by the Crisis Prevention Institute as a guide. Those techniques emphasize verbal responses to calm situations down and physical responses only as a last resort or when there is the threat of imminent danger.

In a phone conversation in late January, the YCA’s commandant, Joseph Mayfield, explained to a reporter how all cadre undergo two weeks of refresher training in deescalation tactics before the start of each session. “I haven’t had no cadre, since I’ve been the commandant, injure any kids,” he said.

Yet the Fort Stewart YCA's own written reports contain accounts that show cadre members resorting to violence as a first tactic.

In one report from 2016 — early in Mayfield's tenure as commandant — a sergeant ordered a teen boy to remove his earring. The boy cursed him and threw a punch at the sergeant's chest, so the man ripped out his earring, splitting his ear so that it required medical attention. The sergeant was suspended for one week without pay.

Such incidents violate the program’s “hands off” rules and include situations where cadre staff used chokeholds to subdue the students.

"It seemed like those guys got an adrenaline rush when they could put their hands on the kids," said Summer Neal, who worked as a cadre at the YCA in 2018. "It seemed like they were just waiting. They just wait to have a reason."

From interviews, the AJC learned of other physical encounters between cadre and cadets that were not documented in the records as required. Some internal investigations ignored evidence of abuse and appeared written to minimize the culpability of staff, the AJC found.

While the AJC was conducting its investigation, along with reporting partner Channel 2 Action News, the Fort Stewart YCA's longtime director was pushed out. Roger Lotson, who is a McIntosh County commissioner and pastors a Baptist church in Darien, told his staff in a letter that "I was asked to retire. While the obvious question is why, that is not important."

Lotson declined interview requests from the AJC and Channel 2, and he did not return messages after his retirement. Maj. Gen. Thomas Carden, appointed adjutant general over the Georgia Department of Defense by the governor last year, would not explain the director's sudden departure.

"I anticipate additional changes at all three of our Youth Challenge campuses," the adjutant general told the AJC. "If we're not a learning organization, and if we run from transparency and we don't take responsibility, we're not going to get better."

But Maj. Gen. Carden said cadets are "absolutely not" being abused at the Fort Stewart YCA. As for the case of a teen having his earring ripped out by an adult, Carden said "regardless of what word we want to attach to it, whether it's abuse, conduct unbecoming, it departs from our basic values.

“The only way for me to drive risk to zero in that program is to not have it,” Carden said. “But I believe that the worst thing that we could do is to be afraid to try to help these young men and women that so desperately need a chance.”

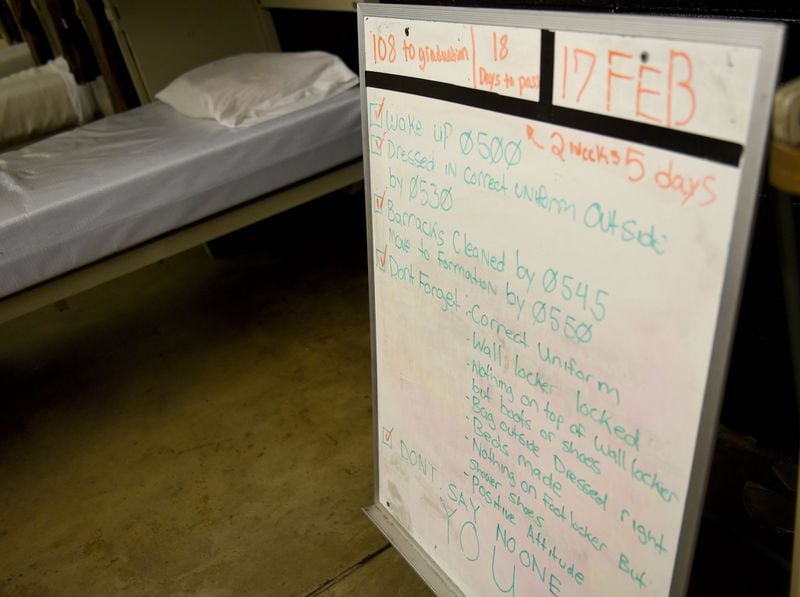

Sessions at the Youth Challenge Academy last five and a half months, with no cost to parents. Cadets wake up at 5 a.m. for physical training, with lights out at 9 p.m. They learn to drill and march. They climb ropes and they can catch up on high school classes at an on-site charter school or study for GEDs. All within the fenced confines of Fort Stewart, a U.S. Army base housing 50,000 soldiers, civilians and family.

The Georgia National Guard allowed the AJC and Channel 2 to tour the academy and observe drills, but reporters were not permitted to interview cadets. And former director Lotson directed other staff not to speak to reporters, a directive that Gen. Carden later rescinded as not in keeping with the guard’s values.

Both Lotson and Mayfield declined subsequent interview requests.

This story is based on the AJC's tour of the academy, incident reports, investigations of sexual harassment and interviews with former staff members and cadets.

‘Techniques used to restrain cadets’

A national controversy over the use of chokeholds erupted in 2014 after the death of Eric Garner while being restrained by a New York City police officer. Most police departments across the country ban the potentially deadly tactic, said Jim Dooley, an adjunct assistant professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice who teaches use of deadly force at the NYC Transit Authority.

In a facility for teens, Dooley said it would be safer to use pepper spray or even Tasers.

"A chokehold, if the airway is constricted, could kill you," the professor said. "I'm thinking an adult male, versus a juvenile, putting probably powerful arms around the neck, and that could constrict the airway. It's really that simple."

That's apparently what happened to the boy removed from a classroom by a drill instructor last April. 1st Lt. Daniel Gamble escorted the 16-year-old boy who had been arguing with another cadet into a classroom and forced him into a desk, holding him down with his hand on the back of the boy's neck. The boy was agitated and swearing and would not remain seated, according to witnesses.

Gamble twisted the boy’s right arm behind his back, then placed his free arm around the boy’s chest and walked the student out of the classroom, lifting him up until he was on his toes. Kayla Rose, a paraprofessional, saw the pair emerge from the class and said Gamble had the cadet “in a chokehold and proceeded to choke him out to the point where he passed out.”

Rose caught the student and hugged him to her.

“Let me help,” she said, according to a witness. “I know him.”

In his own statement, Gamble did not write that he had his arm around the boy’s neck and omitted that the cadet lost consciousness. But Paula Scott, a retired high school principal who was on campus that day, got a good look.

"I looked to my right and saw a male YCA cadre had a male cadet in a headlock," she wrote in her statement.

In his handwritten statement, the boy, whose name is redacted from the reports, said he had gotten into an argument with another boy and wanted to cool off before returning to class.

“He called me a hoe (sic) so I got upset and tried to calm down, and Lt. Gamble came telling me to go inside, but my teacher said I could stay out,” the boy wrote. Describing the incident, the boy wrote that Gamble “put me in a hold a little to (sic) tight and I blacked out.”

The boy said he “didn’t feel abused” by the incident and that Gamble was “still my favorite” lieutenant. In an internal interview, the boy said he understood the academy’s hands-off policy, but thought it did not apply to the adults in charge.

Ex-director Lotson tasked Beatice Palmer, a long-serving cadre member who has replaced him as director, to investigate the matter. In her report, Palmer did not include statements from witnesses saying that Gamble choked the boy. Instead, she defended Gamble’s conduct as reasonable.

» FROM 2014: Col. Thomas Carden tapped to command Georgia Army National Guard

» MORE: Complaints up sharply as Georgia's new sexual harassment policy takes hold

“1LT Gamble stated that the techniques he used is what he has used repeatedly to restrain cadets in the past when needed,” she wrote. “1LT Gamble used other supported techniques to control this situation and maintain control of an irate, uncontrollable, hostile cadet, who was determined to do harm to another cadet if not restrained.”

In fact, Palmer recommended Gamble’s “techniques used to restrain cadets” should be reviewed and approved as permissible.

Lotson made no decision on whether Gamble used an unapproved chokehold. But he noted his “history of violating the (hands-off) policy” led him to believe that he had done so again and he suspended Gamble for one week.

Gamble told the AJC he was no longer employed by the YCA and he had no comment.

“When I voiced my opinion nobody said anything about it then,” he said. “I don’t want nothing to do with the Youth Challenge Program.”

Unreported incidents

Staff are supposed to file a report when place their hands on students, but documents obtained by the AJC show some hands-off incidents go unreported unless someone complains.

Last summer, the mother of one cadet learned about such an incident in a letter from her son, a cadet in the program. The handwritten letter is a mix of optimism for himself and astonishment at the level of chaos and violence he was experiencing.

"Living with 40 other guys is so chaotic. It's fights everyday LITERALLY and boys doing dumb stuff so the MP's 'military police' are here almost everyday," he wrote. "I've witnessed a lot of stuff in here especially fights but man ma it's some coocoo dudes in here."

In writing to his mother about the physical regimen (“we run miles, push-ups, sit ups”) and the food (“they stuff us with good food”), he mentioned the incident with Sgt. Zavier Chance.

“I’m good even though I got choked out by my cadre lol,” he wrote, using shorthand for “laugh out loud.” The boy reassured his mother that everything was OK. “Me and him had a talk the next day because he said he couldn’t sleep after what happened.”

She was not reassured. Instead she drove to the base the following day and threatened to press criminal charges, prompting a hasty investigation.

In a statement apparently taken after the mother’s visit, Chance said he wrestled the boy to the ground for refusing to leave the barracks for talking during “quiet time.” In his written account, he never said he put his arm across his throat.

“While trying to turn around, as he turned a (sic) elbow was coming up I put my right forearm up and grabbed him,” Chance wrote. “He fell straight to the floor before anything even happen.”

But an investigative report said video surveillance showed Chance put his arm across the boy's "upper chest and neck region" and pulled until the boy was on the floor. Three cadets who witnessed the incident said Chance put the boy in "a choke hold."

Although Chance failed to report the hands-off violation, it wasn’t a secret. Ashleigh Carlin, a civilian advisor, said the cadet approached her and another sergeant three days after the incident and asked why his cadre was allowed to choke him.

In her statement, Carlin said she reported the alleged violation and later spoke with Commandant Mayfield about it, but Mayfield apparently shelved the incident until the mother arrived.

Administrators accepted Chance’s version that “he did not use any pressure” when he pulled the boy to the ground.

“The statement of the cadre and review of the video suggests the cadet was not choked,” the report concluded. The report indicates Chance was removed from duty for two weeks for retraining and was under supervised duty for the next three months.

» RELATED: Video of black man's arrest spurs outrage, NYPD probe

» FROM 2018: State's weak response to sexual harassment makes reporting risky

The mother withdrew her son the the program. Chance did not respond to the AJC’s interview requests.

It is not clear how much National Guard leaders knew about the incidents of physical abuse against cadets. In interviews, the AJC learned of other cases that would appear to have violated the hands-off policy and required documentation.

“There’s no guarantee that I have perfect information on everything that goes on in an organization as large as this,” Maj. Gen. Carden said. “But at the end of the day, not knowing is not any excuse. I look at these, again, in the context of not what I knew, but what should I have known, and should I build a better structure.”

A padded isolation room

The AJC’s reporting raised questions about whether the YCA program is equipped to handle the kinds of students sent to it.

Many come from abusive homes or have been traumatized in some way. They do not respond to being yelled and cursed at for rules violations, according to a former counselor at the academy, who asked not to be identified because she was a victim of alleged sexual harassment by a cadre member.

"If all they know is to be aggressive, (then) that's all they know. They don't know any different. And those kinds of behaviors don't go away just because you enter a campus of the YCA," she said. "The cadre took it more as a threat, so they would try to make the cadets feel small, smaller than they already did."

When the children didn’t respond, cadre members disciplined them by making them eat last or not eat at all, she said. Children who got in fights were put in reflective vests to signal to their peers they were in trouble. If they got in trouble again, she said she had seen cadre remove their mattresses.

“That’s the punishment. Make them sleep on the floor, like they are animals,” she said. “Inmates get treated better than these children.”

Some of the teenage cadets did respond to the military-style discipline imposed at the academy, but she said generally those were kids who arrived at Fort Stewart with more advantages.

“They had more supportive parents, they had the means for stuff that they needed. The kids who didn’t have that support system, I don’t feel did as well,” she said.

Incident reports reviewed by the AJC also raise serious questions about how the program’s disciplinary measures impact those who come with prior psychological trauma.

Last October, a teacher discovered a cadet lying unconscious on the ground with a rope tied around his neck and tightened with a stick like a tourniquet. The 16-year-old already had cut himself and told a counselor he would hurt himself. The report of the incident does not indicate how the cadet managed to be unsupervised and outside of the camp buildings.

The report says that Commandant Mayfield responded to the call for help, loosened the rope and revived the youth by pouring water on him. The cadet was taken to the medical department on base where he said “he heard voices in his head to harm himself and others.”

In March of last year, a cadre member found a student “in a daze” after taking “several pills he brought back from his cadet pass.” According to the incident report, the cadet was released to his father and admitted to a psychiatric hospital.

An open records request submitted by the AJC to the National Guard revealed that teen suicide attempts or threats to harm themselves happen frequently. In 2016, five cadets were hospitalized for suicidal thoughts or attempts. According to the reports, some of them had tried to kill themselves before arriving at YCA.

Maj. Gen. Carden said the recruits for YCA are screened before entering, but he said it is not a perfect system.

"We deal with the kids that we get. We screen them as best we can. We do everything we can to set them up for success. And from time to time, we wind up with kids, as you might imagine, high school-aged adolescents, that do things that you'd probably see in just about every high school in this state."

Not every high school has an isolation room, however. The academy’s room, referred to on a log sheet obtained by the AJC as the “padded” room, is a small room with a plastic chair behind a heavy door with a small, narrow window.

Carden described it as a place where agitated youths can “decompress,” especially if they are a harm to themselves or others.

“Again, this is not a prison. This is not a Regional Youth Detention Center. This is not an isolation-type area for those purposes,” he said. “This is a cool-down area for a young man or woman.”

He also said it’s a very temporary space.

“I’m not sure that we’ve got a time clock on it, but I will tell you that it’s minutes not hours,” he said.

In fact, a page from the isolation room’s log sheet from Nov. 12 shows a cadet being locked into the room at 5:45 p.m.

The log does not indicate when he was released, but at one point he was apparently left alone in the room for nearly an hour with no adult to check on him.

‘Structured, routine, disciplined environment’

The isolation room was not included in a campus tour when the AJC and Channel 2 requested permission from the National Guard to view the program.

On a morning in February, reporters heard a boilerplate presentation from Lotson, which included a stroll across the campus grounds with him and Mayfield, as well as looks inside a packed classroom and both boys’ and girls’ empty barracks.

In a room within the cafeteria building, then-Director Lotson gave a speech with Powerpoint slides, explaining how the YCA takes in teens ages 16 to 18 with behavioral problems, mental health issues, low self-esteem and anger issues. He described handling cadets in the throes of alcohol and drug withdrawal, or with schizoaffective disorders, Asberger syndrome and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

“We take what traditional school systems aren’t able to provide for, in many cases,” Lotson said. “We are the last great hope for many of the young people that come to this program.”

Lotson had some of the cadets speak, too, wearing their monochrome uniforms and caps, impassively describing how the YCA pulled them from tough environments and instilled them with discipline and purpose.

A 16-year-old female cadet from Savannah told of being raped and abused as a child, then attempting suicide in ninth grade and being placed in a mental hospital. Another 16-year-old, from Middle Georgia, said her mother’s ex-boyfriend raped her when she was 8.

“From there, my brain wasn’t working properly,” she said, going on to describe how she later became depressed, suicidal and in and out of mental hospitals. “If I had kept going down that path that I was going, I could have been dead.”

A former female cadet, age 17, said she came into the program four months pregnant, then gave birth just before graduation.

"Structured, routine, disciplined environment — that is the secret," Lotson said during his presentation. "That is why we can do with with Johnny and Martha what the traditional high school cannot do."

He then demonstrated the point by ordering a male cadet in the room to drop and give him 10 push-ups.

“School systems cannot do that,” Lotson said.

Tabitha Olsen, the former cadet who spoke to the AJC, recalled being part of a similar tour in 2018 for a group of government representatives. She said in the week leading up to the visit, cadre members gave the girls buckets of paints and ordered them to paint the barracks and bathroom walls, covering the mold.

Olsen said she was also picked to give a speech for the group. Lotson, she said, told her to “be more dramatic.

"They told us specifically to exaggerate on the stories, to make it sound tragic, to make it sound like we were down in the streets," she said.

So Olsen said she told the group about a gang rape, and using methamphetamine, crack cocaine and bath salts — none of which really happened.

“Kinda hurt doing that, just a little,” Olsen said.

The AJC’s tour ended with all the platoons — some 200 cadets — gathered in formation around a flagpole. “I’m proud of you, because you’re still here,” Mayfield told them.

Later, each platoon marched back to their respective barracks in a clamor of boots pounding pavement, and cadence calls between adult drill masters and throngs of teenage voices.

“Sergeant major, can’t you see!”

“Sergeant major can’t you see!”

“What this place has done for me?”

“What this place has done for me?”

Want to share a tip?

Here’s how to reach the reporters on this story:

Chris Joyner — 404-526-5884, cjoyner@ajc.com

Jennifer Peebles — 404-526-5923, jpeebles@ajc.com

Johnny Edwards — 404-526-7209, jredwards@ajc.com