Neon Is the Ultimate Symbol of the 20th Century

The once-ubiquitous form of lighting was novel when it first emerged in the early 1900s, though it has since come to represent decline.

In the summer of 1898, the Scottish chemist Sir William Ramsay made a discovery that would eventually give the Moulin Rouge in Paris, the Las Vegas Strip, and New York’s Times Square their perpetual nighttime glow. Using the boiling point of argon as a reference point, Ramsay and his colleague Morris W. Travers isolated three more noble gases and gave them evocative Greek names: neon, krypton, and xenon. In so doing, the scientists bestowed a label of permanent novelty on the most famous of the trio—neon, which translates as “new.” This discovery was the foundation on which the French engineer Georges Claude crafted a new form of illumination over the next decade. He designed glass tubes in which neon gas could be trapped, then electrified, to create a light that glowed reliably for more than 1,000 hours.

In the 2012 book L’être et le Néon, which has been newly translated into English by Michael Wells, the philosopher Luis de Miranda weaves a history of neon lighting as both artifact and metaphor. Being and Neonness, as the book is called in its English edition, isn’t a typical material history. There are no photographs. Even de Miranda’s own example of a neon deli sign spotted in Paris is re-created typographically, with text in all caps and dashes forming the border of the sign, as one might attempt on Twitter. Fans of Miami Beach’s restored Art Deco hotels and California’s bowling alleys might be disappointed by the lack of glossy historical images. Nonetheless, de Miranda makes a convincing case for neon as a symbol of the grand modern ambitions of the 20th century.

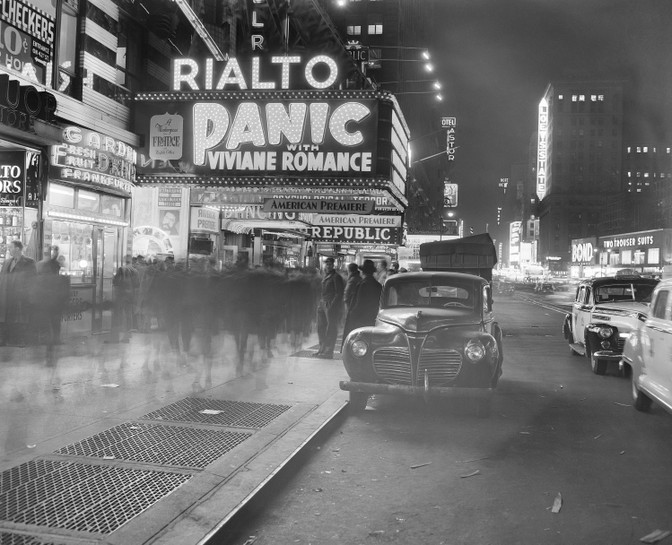

De Miranda beautifully evokes the notion of neon lighting as an icon of the 1900s in his introduction: “When we hear the word neon, an image pops into our heads: a combination of light, colors, symbols, and glass. This image is itself a mood. It carries an atmosphere. It speaks … of the essence of cities, of the poetry of nights, of the 20th century.” When neon lights debuted in Europe, they seemed dazzlingly futuristic. But their husky physicality started becoming obsolete by the 1960s, thanks in part to the widespread use of plastic for fluorescent signs. Neon signs exist today, though they’ve been eclipsed by newer technologies such as digital billboards, and they remain charmingly analog: Signs must be made by hand because there’s no cost-effective way to mass-produce them.

In the 1910s, neon started being used for cosmopolitan flash in Paris at precisely the time and place where the first great modernist works were being created. De Miranda’s recounting of the ingenuity emerging from the French capital a century ago is thrilling to contemplate: the cubist art of Pablo Picasso, the radically deconstructed fashions of Coco Chanel, the stream-of-consciousness poetry of Gertrude Stein, and the genre-defying music of Claude Debussy—all of which heralded a new age of culture for Europe and for the world.

Amid this artistic groundswell, Georges Claude premiered his neon lights at the Paris Motor Show in December 1910, captivating visitors with 40-foot-tall tubes affixed to the building’s exterior. The lights shone orange-red because neon, by itself, produces that color. Neon lighting is a catchall term that describes the technology of glass tubing that contains gas or chemicals that glow when electrified. For example, neon fabricators use carbon dioxide to make white, and mercury to make blue. Claude acknowledged at the time that neon didn’t produce the ideal color for a standard light bulb and insisted that it posed no commercial threat to incandescent bulbs.

Of course, the very quality that made neon fixtures a poor choice for interior lighting made them perfect for signs, de Miranda notes. The first of the neon signs was switched on in 1912, advertising a barbershop on Paris’s Boulevard Montmartre, and eventually they were adopted by cinemas and nightclubs. While Claude had a monopoly on neon lighting throughout the 1920s, the leaking of trade secrets and the expiration of a series of patents broke his hold on the rapidly expanding technology.

In the following decades, neon’s nonstop glow and vibrant colors turned ordinary buildings and surfaces into 24/7 billboards for businesses, large and small, that wanted to convey a sense of always being open. The first examples of neon in the United States debuted in Los Angeles, where the Packard Motor Car Company commissioned two large blue-and-orange Packard signs that literally stopped traffic because they distracted motorists. The lighting also featured heavily at the Chicago Century of Progress Exposition in 1933 and at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. At the latter event, a massive neon sign reading Futurama lit the way to a General Motors exhibition that heralded “The World of Tomorrow.”

De Miranda points out that businesses weren’t alone in embracing neon’s ability to spread messages effectively. By the middle of the century, the lighting was being adopted for more political purposes. “In the 1960s, the Soviets deployed a vast ‘neonization’ of the Eastern bloc capitals to emulate capitalist metropolises,” de Miranda writes. “Because consumer shops were rare in the Polish capital [of Warsaw], they did not hesitate to illuminate the façades of public buildings.” In other words, as opposed to the sole use of the more obvious forms of propaganda via posters or slogans, the mass introduction of neon lighting was a way of getting citizens of Communist cities to see their surroundings with the pizzazz and nighttime glamour of major Western capitals.

Neon, around this time, began to be phased out, thanks to cheaper and less labor-intensive alternatives. In addition, the global economic downturn of the 1970s yielded a landscape in which older, flickering neon signs, which perhaps their owners couldn’t afford to fix or replace, came to look like symbols of decline. Where such signs were once sophisticated and novel, they now seemed dated and even seedy.

De Miranda understands this evolution by zooming out and looking at the 1900s as the “neon century.” The author draws a parallel between the physical form of neon lights, which again are essentially containers for electrified gases, and that of a glass capsule—suggesting they are a kind of message in a bottle from a time before the First World War. “Since then, [neon lights] have witnessed all the transformations that have created the world we live in,” de Miranda writes. “Today, they sometimes seem to maintain a hybrid status, somewhere between junkyards and museums, not unlike European capitals themselves.”

Another mark of neon’s hybridity: Its obsolescence started just as some contemporary artists began using the lights in their sculptures. Bruce Nauman’s 1968 work My Name as Though It Were Written on the Surface of the Moon poked fun at the space race—another symbol of 20th-century technological innovation whose moment has passed. The piece uses blue “neon” letters (mercury, actually) to spell out the name “bruce” in lowercase cursive, with each character repeated several times as if to convey a person speaking slowly in outer space. The British artist Tracey Emin has made sculptures that resemble neon Valentine’s Day candies: They read as garish and sentimental confections with pink, heart-shaped frames that surround blue text fragments. Drawing on the nostalgia-inducing quality of neon, the sculptures’ messages are redolent of old-fashioned movie dialogue, with titles such as “You Loved Me Like a Distant Star” and “The Kiss Was Beautiful.”

Seeing neon lighting tamed in the context of a gallery display fits comfortably with de Miranda’s notion that neon technology is like a time capsule from another age. In museums, works of neon art and design coexist with objects that were ahead of their own time in years past—a poignant fate for a technology that made its name advertising “The World of Tomorrow.” Yet today neon is also experiencing a kind of craft revival. The fact that it can’t be mass-produced has made its fabrication something akin to a cherished artisanal technique. Bars and restaurants hire firms such as Let There Be Neon in Manhattan, or the L.A.-based master neon artist Lisa Schulte, to create custom signs and works of art. Neon’s story even continues to glow from inside museums such as California’s Museum of Neon Art and the Neon Museum in Las Vegas. If it can still be a vital medium for artists and designers working today, “neonness” need not only be trapped in the past. It might also capture the mysterious glow of the near future—just as it did a century ago.