Why are carrots orange? That’s not the set-up of a Michael McIntyre gag – it’s a serious question. And the answer sums up the forces at play in the production of modern, genetically modified foods: science, fashion and, above all, politics.

Our ancestors knew carrots, but not as we do. Theirs were short and stubby, like a radish, and came in yellow, white, purple or red. But not orange. In the 17th century, the Dutch were the world’s leading vegetable technologists, and the carrot was just one of the staples they decided to “improve”.

Through selective breeding, they made it sweeter and less woody and, over time, it became the recognisable root vegetable that sprouts in gardens and fields worldwide today. Its hue is where the politics comes in: according to lore, the Dutch breeders bred their carrots to honour their ruler, William of Orange, upholder of the Protestant faith and, from 1689, king of England, too.

Selective breeding is genetic modification: it is the engineering of DNA, the code within cells. You see its results in the supermarket vegetable aisle and in household pets. It’s what makes a dachshund look so different from a Great Dane, even though they are of the same species. This is evolution, accelerated and directed in the way that we humans want it to go – in the case of dogs, to make something playful and charming out of wolves.

The thoroughbred racehorse is the product of more than three centuries of DNA tweaking, by pairing the best male with the best female. Despite his own family’s enthusiasm for this particular form of genetic modification, Prince Charles has objected to humans “playing God” with nature. But, as the scientist Richard Dawkins countered, “We’ve been playing God for centuries!”

Intelligent Design

The problem with acquiring godlike powers is that you’re likely to make full use of them. When gene-altering techniques first moved from the greenhouse to the laboratory, scientists focused on helping growers: offering greater yields, reducing reliance on pesticides, or developing fruit and veg with a longer shelf life. That’s how we’ve ended up with mushrooms that don’t go brown and tomatoes that are more evenly spaced on a plant’s branches, so they can be harvested more easily by machine. (And, in the animal kingdom, salmon that grow twice as fast.)

But the latest crop is different. The new genetically modified organisms (GMOs) promise benefits to you, the consumer. Making food healthier has become a central goal of commercial users of the technology, not least because it’s a way of winning over sceptics. There’s wheat whose gluten doesn’t trouble coeliac sufferers, “millennial pink” pineapples enriched with anti-cancer nutrient lycopene, and white bread engineered to be higher in fibre. God’s work is being updated, and it seems unlikely that even Prince Charles can stop it.

In the coming decade, the number of new, health-focused crops is expected to increase exponentially. This is partly a result of a new DNA-editing technique, Crispr (short for “clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats”), which works with native characteristics in a way that could occur in the wild, only with unprecedented accuracy. This differs from previous GM methods, in which a copy of a gene from one organism would be placed in another with which it couldn’t naturally reproduce.

What Is Crispr?

It may sound like yet another gluten-free food start-up in east London, but Crispr is a new molecular system that scientists can use to manipulate DNA – more quickly, simply and accurately than ever before. As well as its many potential applications in making our fruits richer in nutrients or our grains resistant to climate change, it could also one day be used to engineer human embryos – although there are significant ethical considerations.

At the sharp end of this new tech is Geoff Graham, vice-president of plant breeding at US-based company Corteva Agriscience, which has created plant oils modified to contain higher levels of monounsaturated fats.

“Both Crispr and genetic modification can be used to improve nutritional quality,” he says. “For example, Crispr is being used in tomatoes to make them healthier by increasing their levels of Gaba [gamma-aminobutyric acid, linked to better sleep and lower blood pressure]. It’s also being explored as a tool to reduce the harmful reactions some people have to certain foods – such as peanuts that don’t trigger allergies.” Corteva’s oil, called Plenish, is made from soya beans modified to contain 20% less saturated fat than they normally would. It’s also more stable during cooking.

At a time when poor diet is a factor in one in five deaths around the world – and nutrition education isn’t making enough of an impact – these lab-produced superfoods seem to offer a logical solution. After all, if we won’t change our habits, surely striving to improve the foods we’re already eating is a worthwhile pursuit?

Even foods long considered “healthy” have suffered a nutritional hit in recent years, as intensive farming has decreased the levels of vitamins and minerals present in our fruit and veg. This new, nutrition-boosting technology could be our best chance of rectifying that – but, of course, not everyone is convinced.

Suspicious Minds

The most significant concern is the risk to our health. In trying to solve one problem, do we risk creating a worse one? Recent studies into GM tech have found worrying effects that could have a bearing on humans. One paper in the journal Plos One described butterflies with deformed wings that had been feeding on GM oilseed plants, altered to produce healthy omega-3 fats. But how could the researchers be sure what deformed the butterflies? And would humans be similarly affected?

Michael Antoniou of King’s College London works in gene therapy – in particular, the adaptation of genes to address genetically based diseases. “There are claims from the United States that no one has been harmed by eating GM foods. But no one has actually looked,” he says. “Increasing numbers of lab studies on rats and mice are showing evidence of harm, mostly on the function of the kidney, liver and, to some extent, digestive and immune system function.” He believes a GM diet “could cause the adverse effects observed in these studies”.

Antoniou’s views are controversial. While he and his colleagues are part of a network of hundreds of scientists who campaign with green groups for restrictions on GM research, they are not the mainstream. Worldwide, more scientists are pro-GM than against.

One major complaint of the pro-GM lobby is that public fear and governmental caution – especially in Europe – are stalling the progress of research into techniques with potentially vast benefits. Among the scientists speaking out for a more open-minded approach is Jayson Lusk, professor of agricultural economics at Purdue University in Indiana. “It’s just a tool, and a tool can be used in good or bad ways,” he says. “A blanket rejection of a tool is a naive, uncritical position. We need a case-by-case evaluation.”

The future lies with the general public, as well as with politicians – and, at the moment, both are wary of the technology. Lusk’s research into US consumer attitudes shows that, if anything, the GM industry has itself to blame for these public fears. In the US, where almost 90% of staple crops such as corn, soy, cotton and sugar beet are GM, consumers “know very, very little” about the technology.

The industry prefers it that way, and it campaigned unsuccessfully against a 2016 law that will soon make the labelling of GM products mandatory. This viewpoint might have made some sense when the use of GM offered no clear benefit to the consumer. But with the arrival of, say, gluten-free loaves, companies may decide to reconsider their position. In any case, transparency appears to work better. In Vermont, the only American state where it is already mandatory to label products, consumer resistance to the technology has fallen. Labels give people a sense of control, and so of lower risk.

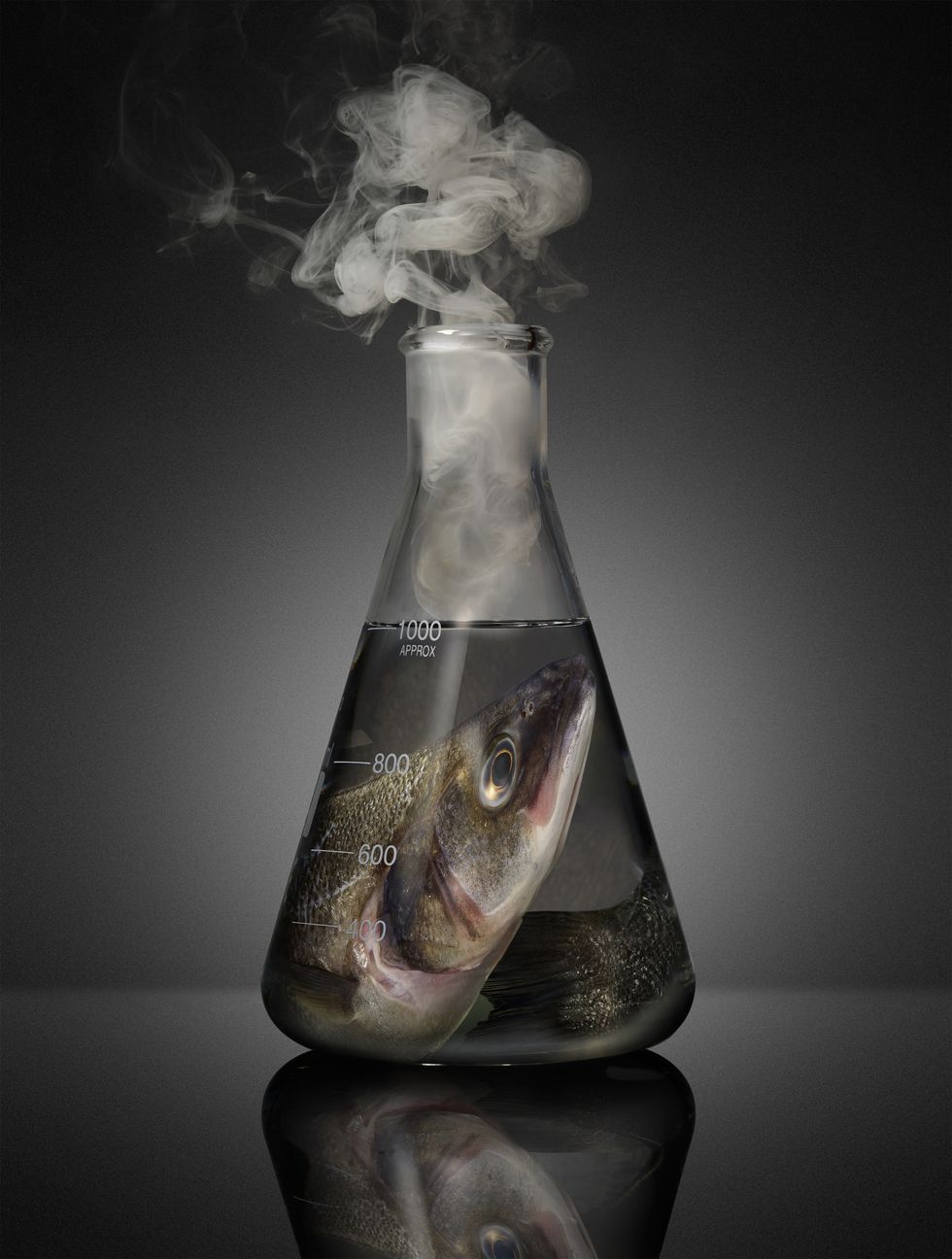

It’s hard to predict whether the introduction of the new GM superfoods will change minds but, at present, opinion appears to be hardening against the technology, even while the US campaigns for Europeans to accept it. Transgenic salmon – which contains DNA from different species and grows twice as fast – was given the all-clear for health in the US three years ago, but it’s still having trouble reaching your fishmonger’s slab.

Like many academics, Lusk believes that “naive” opposition to GM is counterproductive – that the technology’s benefits are too great to allow instinctive fears to rule it out. And healthier food is arguably not the most pressing issue. GM’s greatest benefit lies in its potential to help feed the 9.8 billion people who will inhabit this planet by 2050, as climate change makes it increasingly difficult to grow crops in regions that were previously suitable.

Modifications to animals are also on their way, though these tweaks aren’t quite as extreme as those in science-fiction, such as the super-chicken in Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake, which had no eyes or legs, just 20 breasts and a mouth. More subtle but hugely important are alterations to animals’ gut bacteria, enabling them to eat waste crops such as straw, and, in the case of pigs and cows, produce less methane (a major cause of global warming).

The Next Generation

Ultimately, it may be cool logic, rather than an appetite for cancer-fighting fruit, that changes minds. In the 1990s, author Mark Lynas was an eco-warrior. He and his friends were determined to stop big corporations corrupting nature for profit. They went out on late-night raids to destroy GM crops being grown in laboratory farms, and he once threw a pie in the face of an eminent pro-GM economist. The efforts of campaigners like Lynas led to companies such as Monsanto becoming global bogeymen, accused of trapping farmers with their patented GM seeds and the chemicals that had to be used with them.

But Lynas’s name is now a dirty word at Greenpeace and other environmental campaign groups. He has become one of the anti-GM movement’s noisiest critics, and considers it hypocritical. “You can’t defend the scientific consensus on [the risks of man-made] climate change, while denying the equally strong scientific consensus that GM is a safe technology with huge potential benefits,” he says.

In Seeds of Science: Why We Got It So Wrong on GMOs, published earlier this year, Lynas accuses the anti-GM campaign of denying us this tech for no reason other than unscientific prejudice. “GM, like washing machines or cars, is a technology and we have to make a political decision … as to whether we want to use it or not and the extent to which we want to use it,” science writer George Monbiot tells Lynas in the book.

Politicians have dithered over gene-altering technology for years. Currently in Britain, as in the rest of the EU, unless you are strictly organic or vegan in your diet, you are almost certainly eating GM at one remove, because GM animal fodder is legal for use here. But Europe is keeping a wall up against the further intrusion of GM: after months of debate, the European Court of Justice ruled that new gene-editing technologies such as Crispr should fall under the same controls as the older splicing methods.

Yet progress is being made. In Costa Rica, those pink pineapples are still growing, having received the stamp of approval from the US Food and Drug Administration. Last year, researchers from Australia showcased an orange banana with high levels of pro-vitamin A, developed to treat nutrient deficiencies in Uganda. With Western tastes in mind, scientists at the Sainsbury Laboratory in Norwich are currently modifying potatoes to create healthier chips.

With such tools now available, it seems unlikely that humans can be prevented from exploiting them. Whether that’s good or bad, safe or concerning, remains a matter of debate. Yet one thing is certain: the future of food is coming ever closer.

The Superfoods of Tomorrow

01/ Meat-Free Burgers

The vegan Impossible Burger – engineered to taste, smell and feel like a hunk of beef – might indeed be impossible without soy leghemoglobin, made using GM yeast. The burger is sold across the US.

02/ Healthier Chips

Sold in the US since 2015, Simplot Plant Sciences’ White Russets contain less amino acid asparagine, which could reduce levels of carcinogenic acrylamide when fried.

03/ Low-GI Bread

Calyxt is developing a wheat that could produce white flour with triple the fibre, for a gentler glucose spike. It hopes to launch in the US within two years.

04/ Vegan “Fish Oil”

By adding genes from algae to camelina plants, a team at Rothamsted Research, Hertfordshire, has created a plant oil that’s rich in omega-3 – fatty acids found in fish. Good for the planet, as well as your salad

05/ Purple Tomatoes

Produced at the John Innes Centre in Norwich, these tomatoes contain higher levels of heart-protecting anthocyanins, which give berries their hue. The fruit has been shown to have an anti-cancer effect in mice