Healthcare workers on the frontlines of the fight against the coronavirus have been enduring long hours and distance from their families while risking their lives to care for patients. Those of us at home feel a deep appreciation for their heroic work. You can see signs of our gratitude in thank-yous on highway billboards, sentimental social posts, and in some cities, daily applause at sunset.

But it’s not just doctors and nurses caring for patients with coronavirus—many others have played a role, from those who clean hospitals to respiratory therapists and social workers. Here are a few of the pandemic’s unsung healthcare heroes from the New York City metro area’s hard-hit hospitals.

Social workers are “the problem-solvers for all the problems that no one else can solve,” says Elisa Vicari, LCSW, a social worker in the intensive care unit at North Shore University Hospital. She spends her days consoling COVID-19 patients and their families, sending condolences to the families of patients who die, and providing words of congratulations to patients when they're finally discharged.

During the height of the pandemic, she gained hope from patients who overcame the impossible and beat coronavirus, she says. "This was the most motivating thing that kept me pushing and fighting for those true miracles,” Vicari says. “I’ll carry those ‘wins’ with me forever.”

At her hospital, family members can briefly see patients in end-of-life situations, and Vicari coordinates these visits. She helps visitors get dressed in PPE, talks to them about their grief, and lets them know when it’s time to say goodbye. When a patient’s family is unable to visit in person, Vicari facilitates video calls to allow people to see their loved ones one last time. “I stand there holding the screen, watching the desperate faces cry on the other end, and hold the hand of the patient alone in front of me,” says Vicari.

Although the patients are often on ventilators and unresponsive, she gets to know them deeply. Vicari sees family members and pets, hears favorite songs and inside jokes, and is a witness to private, vulnerable moments. “I feel privileged to be the key that keeps these families together,” she says.

Often, she stays late or heads into the ICU even when she’s not scheduled to work. “The hardest thing for myself and my team is when the patients die alone—it’s hard to even think about. It’s a level of pain, sadness, and grief that only those who went through it can know.” she says.

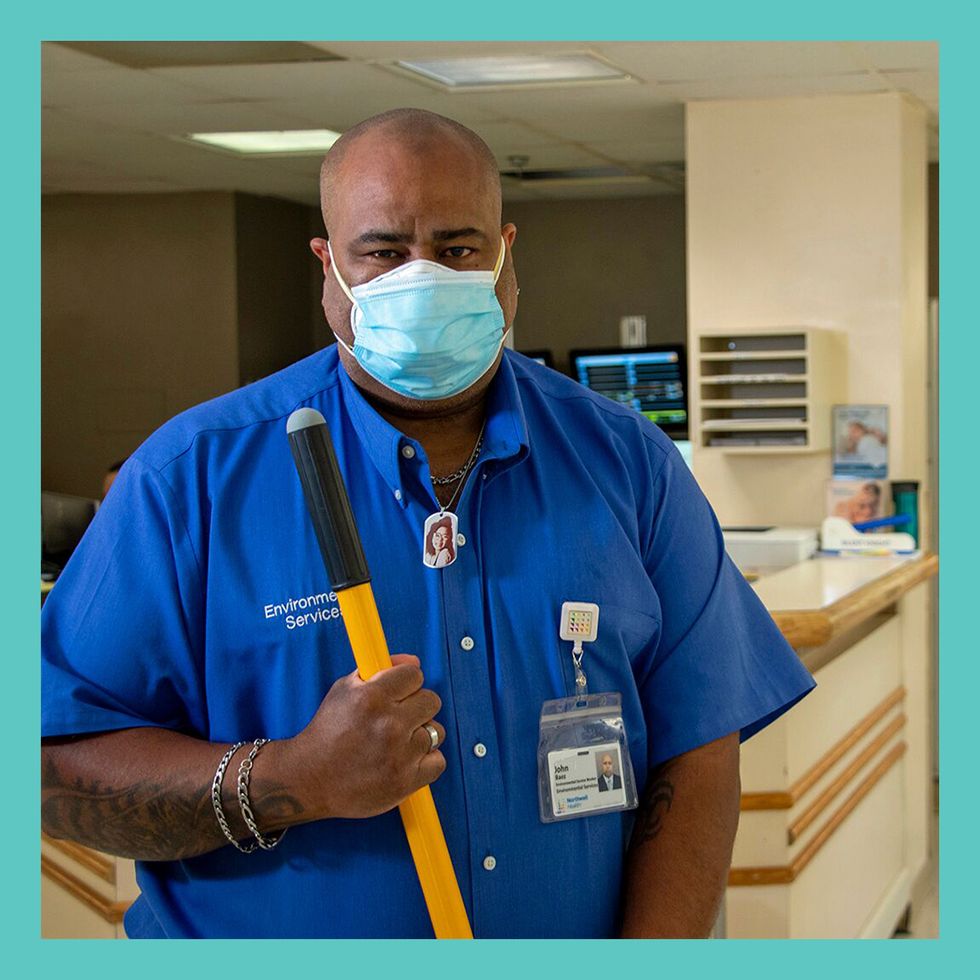

For 11 years, John Baez has worked in environmental services at Staten Island University Hospital, cleaning and disinfecting patients’ rooms. The highly infectious coronavirus has made his work more important than ever. Baez never hesitated about showing up for work during the pandemic, although sometimes his family was concerned for his health.

“This is my job; it’s my responsibility to make sure the patients’ rooms are clean," Baez says. "I had to be here.” He cleans rails, walls, beds, doorknobs, and any other potentially germ-covered surface, leaving the scent of disinfectant in his wake, along with good cheer.

“When I reach the hospital’s front door, I come in with open arms and a big smile on my face,” Baez says. Every shift, he walks through his unit, calling out good morning. “I have a job to do, but I always take a few minutes to talk to the patients and nurses,” he says. Some days, he says, he plays Motown music to lift the mood, and “everyone instantly smiles.”

On her birthday in March, 27-year-old Alison Laxer, MD, found out she could graduate medical school early and care for COVID-19 patients. As a newly minted doctor, she was a bit nervous, and knew she’d miss seeing—and hugging—her parents, who she’d need to avoid for their safety. “I was used to seeing them weekly. This was going to be a big change,” Dr. Laxer says. Still, her decision was clear: “The world was going through a devastating time," she says. "I knew if I could help in any way that it would be worth it.”

For four weeks, Dr. Laxer worked at North Shore University Hospital, screening patients with coronavirus to see if they were eligible to participate in a coronavirus clinical trial for an over-the-counter heartburn medication with the potential to ease the severity of coronavirus symptoms. Early on, she felt concerned for her own health—it was hard not to be fearful that she would catch the coronavirus, even when wearing personal protective equipment (PPE). It got warm under all those layers—some days, her face mask would fog up, and she’d worry her mask wasn’t properly sealed.

But these anxieties never stopped her from meeting one-on-one with patients to share details about the study. “I am glad that I was able to help,” Dr. Laxer says. She’ll take her renewed confidence and comfort interacting with patients who have COVID-19 with her to her next role, working in pediatrics.

Sharon Pollard has over three decades of experience in healthcare and respiratory care. But patients hospitalized with the coronavirus at Long Island Jewish Medical Center and Cohen Children’s Medical Center were different from others she’d encountered previously, she says. “This pandemic required all hands on deck as many patients decompensated really fast and needed ventilators,” Pollard says.

There was plenty of news coverage about the urgent need for ventilators, Pollard points out. But mentions of respiratory therapists—those who work to help patients breathe by monitoring oxygen intake and assisting with breathing tube insertion—were less frequent, she says. “We are at the frontline using various techniques to help patients breathe with the hope of averting the need for a ventilator wherever possible,” Pollard says.

Pollard has a lot of managerial responsibilities. But the surge of patients pushed her into a more hands-on role, caring for patients. Walking into the hospital at the start of a shift, she’d wonder what she’d face—and what more she could do to help patients. “We were all terrified of the unknown,” she says. But when she felt anxiety mount, Pollard worked to stay positive—for herself and her team. “We are not only coworkers but a family,” she says, noting that they needed each other to get through the crisis.

At her medical center, the deluge of patients has eased. For respiratory therapists, the focus is now to get patients off ventilators and help them rehab. Still, Pollard won’t ever forget about the height of the COVID-19 crisis. “The magnitude of loss in such a short period really affected me even after so many years in the healthcare field,” she says.