- India

- International

The prodigal son returned: Author Benyamin on his return to India

Till he reached Bahrain in 1992, the only book Benny Daniel knew was the Bible. But after writing 17 books, including the humongous bestseller, Goat Days, Benyamin has finally left the Gulf behind for the green at home.

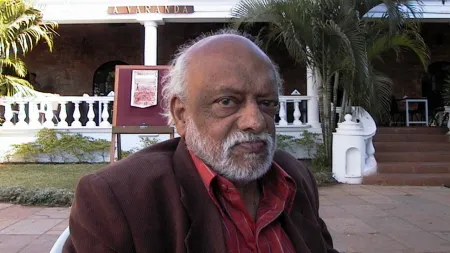

In 2008, Benny Daniel’s life as a writer changed with Aadujeevitham. It won the Kerala Sahitya Akademi Award in 2009, was shortlisted for the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature and longlisted for the Man Asian Literature Prize. (Source: Sugeeth Krishnan)

In 2008, Benny Daniel’s life as a writer changed with Aadujeevitham. It won the Kerala Sahitya Akademi Award in 2009, was shortlisted for the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature and longlisted for the Man Asian Literature Prize. (Source: Sugeeth Krishnan)

Benny Daniel is a “Gulf-returned Malayali”, a grammatically challenged phrase that is used to describe a Keralite who has come home for good after working for many years in the Middle East. In Pandalam, about 100 km from Thiruvananthapuram, just off the highway specked with white churches and Sabarimala pilgrims dressed in black, drive across a small grove of wide-leaf banana plants heavy with fruit, cocoa and rubber trees — the signature flora of this part of Kerala — and you will reach a white, modern house. He greets you, wearing an orange tee and a regular white mundu with a narrow black border. He smiles warmly, and the seriousness that you have come to associate with the photographs of his taciturn, bearded face collapses. His passport holds the name: Benny Daniel, 44, who left his job as a project manager in Bahrain in 2013 to settle down in this old patch of land where his family has lived for four decades. His books carry a different name: Benyamin, the author of the humongous bestseller Aadujeevitham (Goat Days) that has gone into its 100th print run in Malayalam.

His 2011 novel, Manjaveyil Maranangal, which has sold over 40,000 copies, has now been translated into English as Yellow Lights of Death (Penguin Random House) by Sajeev Kumarapuram.

In the living room, there is a crown of thorns mounted on wood, sanctified by the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, and a couple of nails beside it. “Like any Christian boy in Central Travancore, the only book I read was the Bible,” says Benyamin. The second child of Daniel, a taxi driver, and Ammini, a homemaker, young Benny’s life was steeped in cricket and Christianity. At the age of 21, after doing a diploma course in mechanical engineering from a polytechnic in Coimbatore, he flew to Bahrain. “I loved mathematics. I did not take literature seriously until I reached Bahrain,” he says.

There, his friends introduced Benyamin to books. “I had lost the green of my land and its waters. I started reading once I got back from work. One year I read about 140 books,” he says. And then he began to write, first stories, then novels, hiding behind the pseudonym Benyamin. “I had no connection with literature until then, so I was wary of revealing my identity,” he says.

His works — Benyamin has written 17 books so far, including memoirs and short story collections — have two overarching themes: Christianity and the Middle East. “That is because I have spent my life in both Christianity and the Middle East,” he says.

In 2008, Benyamin’s life as a writer changed with Aadujeevitham. It portrayed the hollowing alienation of the Gulf Malayali like no other book ever had: the loneliness, servitude and despair of Najeeb in a goat pen in the vast barrenness of a Saudi desert, was written in a sparse, psalm-like style. It won the Kerala Sahitya Akademi Award in 2009, was shortlisted for the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature and longlisted for the Man Asian Literature Prize. It has been translated into seven languages, including Arabic, although it is banned in Saudi Arabia and the UAE. “My writing hasn’t changed, but I am more recognised as a writer after Aadujeevitham,” says Benyamin, who has just returned from the Dhaka Literary Festival.

Yet, Benyamin is met with disdain and condescension from sections of the greying literary establishment in Kerala. “I don’t think they were equipped to measure that book. What they read so far, the theories they believed in, did not prepare them for it,” says Benyamin, with a nonchalance that must have become a habit by now.

He swears by writers and writing practices that will furrow the highbrow. Many, for instance, would palpably cringe at any comparison with Dan Brown. But Benyamin says, “If you can’t hook the readers in the first five pages, you have lost them. Dan Brown knows how to do that.”

Yellow Lights of Death is Dan Brown-ish in that it is a murder mystery, lightly wrapped around the little-known history of the Chaldean Syrian Christians of Kerala. Numbering a few thousand now, they rejected the Portuguese attempts to Latinise their rites at the Coonan Cross Oath in Mattancherry, way back in 1653. Yellow Lights even has a secret room filled with the Gospels of Thomas, Magdalene and Judas and The Book of Prahan, “which says Joseph had other wives and children before marrying Mariam”.

“It is just my wish-fulfilment. I fantasise that some of the Chaldean texts were saved from being burned by the Roman Archbishop Menezes at the Synod of Diamper (which is how the Portuguese pronounced Udayamperoor) near Kochi in 1599,” says Benyamin. “Udayamperoor was also the capital of the Villarvattom kings, possibly the only Christian dynasty in Kerala.”

Benyamin blends this history with fiction. “I am interested in fictional realism. I want to remove the barriers between reality and fiction so that readers won’t know where one ends and the other begins,” says Benyamin. To that end, Benyamin often becomes a major character in his novels and stories. “I fall in love and make love in my stories,” he laughs.

In Yellow Lights, the writer Benyamin and his real-life friends are looking to unravel a secret that originates in Diego Garcia and ends in Udayamperoor. The readers of the Malayalam original, Manjaveyil Maranangal, have often googled Diego Garcia to see if it was indeed how he described it in the novel: “Our lives are moored to the lagoons. Houses that extend into the lagoons; front yards that walk up to the lagoons; shops that open up to the lagoons; churches with steps leading up from the lagoons; temples that face the lagoons; mosques that summon to prayer beside the lagoons.”

But there are no temples or mosques in the real Diego Garcia. It is a place that Benyamin has never been to. That atoll, curled like an earthworm in the Indian Ocean, is a US military base. “Diego Garcia” was just a whisper Benyamin heard over and over again in Bahrain where he was a project manager of a company that was working for the US Navy. The officers would say, “I have to go to Diego Garcia.” Benyamin borrowed it for Yellow Lights. He, however, scrubbed the place clean of American soldiers. Instead, he populated it with Malayali and Tamil immigrants who look to India as the mainland.

It is a carefully structured novel — there is a story within a story, with two writers, two mysteries and two churches in Diego Garcia and Udayamperoor mirroring each other — so much so that the plot and the thread of history are more interesting than the characters.

“I think a writer’s creativity rests in form. I keep experimenting with it,” he says. It is especially evident in his new work in Malayalam, a double novel: Al-Arabian Novel Factory, about a fictional Arab city, which comes with Mullappoo Niramulla Pakalukal (Days As White As Jasmine), which he pitches as a novel written by a Pakistani girl, based on her experiences. It is around the Jasmine Revolution that sprang up in December 2010 and was quelled in the Middle East by January 2011. In Bahrain, he watched it unfold from his third-floor apartment with delight, dismay, fear and despair.

A “Gulf-returned Malayali” is usually jobless in Kerala. But Benyamin has enough work. He sits with his HP laptop in a book-lined room that is a study in brown. It is a quiet house with few distractions. His wife Asha is still in Bahrain, working as a nurse. Their two children are at a boarding school not too far from Benyamin’s house. He lives with his father, whipping up meals for both of them before settling down to read and write.

He is pottering around a novel about liberation theology in Kerala — why hasn’t Christianity and Communism come together, like they did in Latin America? He has a software that transliterates what he types in English into Malayalam. Benyamin is not the Malayalam writer who swears by the purity of the script. “Language keeps evolving. Manglish, the internet language of the Malayali, has revived Malayalam. You have to be up-to-date, whether it is language or technology. I write for the new generation,” he says and smiles to himself. He can get down to writing. He has an easy day when I meet him: there is leftover rice and beef curry in the fridge.

Charmy Harikrishnan is a journalist based in Thiruvananthapuram.

Apr 29: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05