How Quickly an Unfounded Fear Can Become Reasonable Caution

My grandfather spent his whole adult life separated from his parents. The fear I inherited of being cut off from my own family feels validated by the pandemic.

Upon my return to Taiwan from New York last month, I had to undergo a 14-day quarantine. I intended to use my time wisely. I was finally going to finish edits to my novel, which had taken a back seat to other things in my life—teaching, freelance work. But of course, that’s not what happened. Confronted with the realities of self-quarantine, I discovered I couldn’t bear to look at my book. My difficulty focusing wasn’t just due to the relentless onslaught of pandemic-related news—though that was certainly part of it—but rather that sitting with my plot brought to the surface deep-seated, inherited family trauma.

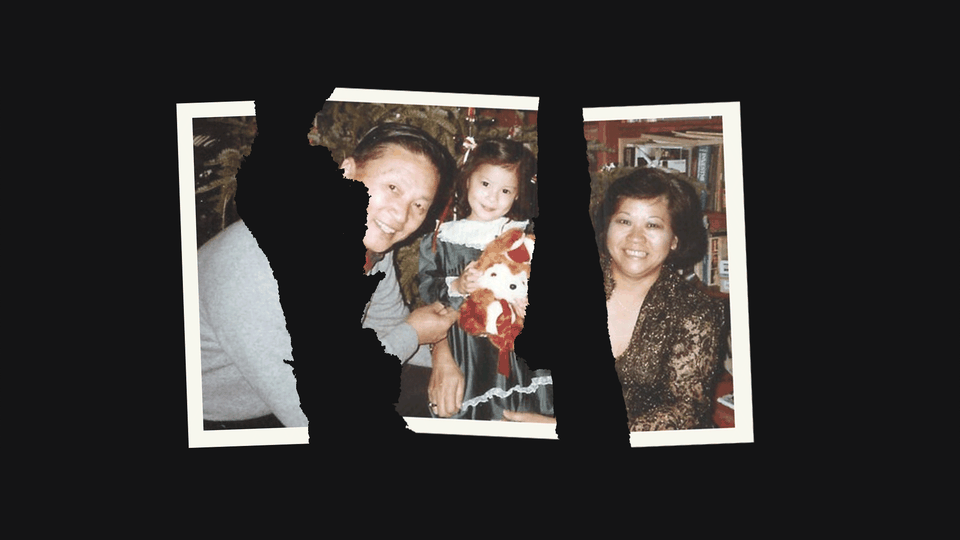

My novel, which is about two childhood sweethearts who are separated from each other and their families as a result of the Chinese Civil War, is inspired by the lives of my grandparents, in particular my maternal grandfather. In 1949, when my grandfather was 19 and the war was nearing its end, his father put him on a boat from Shanghai to Taiwan for a “vacation.” Within months, the Chinese Communist Party declared victory and closed the borders. It became impossible for my grandfather to return home; he would not set foot in Shanghai for nearly 50 years, by which time both his parents had died.

My grandfather’s story fascinated me when I was a child. I felt sad for him—I couldn’t imagine being permanently separated from my family. And, with age, that sadness transformed into deep grief as I recognized that my grandfather had spent his entire life shouldering this quiet, boundless pain. But I felt something else, too: an irrational terror that the same thing could happen to me. Over the years, this fear was quelled by an understanding that, unlike my grandfather, I lived in relatively stable and peaceful conditions, that there was no way that what had happened to him in China in the late ’40s could happen to me. But now I’ve found myself in a collective nightmare.

I moved to Taiwan several years ago for a Fulbright. Because the bulk of my family is now back in the U.S., I divide my time between the two countries, spending several months of the year in New York and New Jersey with my family or attending work-related events. In early March, shortly before the coronavirus started to dominate national headlines, I flew to San Antonio to attend a writing conference, and planned to spend the following week visiting family before finally returning to Taiwan. But then things in the U.S. changed rapidly. Within days of my arrival in New York, both the NBA and Broadway shut down, and by the weekend, the number of confirmed cases in the city alone had exploded.

I started checking my flight status and Taiwan’s CDC site obsessively. I knew there was a possibility that my flight would be canceled or that Taiwan would bar Americans from entering as a preventative measure; it had already restricted travelers from China, Hong Kong, and Macau months earlier because of COVID-19. And yet, even as I fretted, a part of me wondered: Wouldn’t it be a good thing to be trapped here? Shouldn’t I hunker down and weather this storm with my family?

Still, the rational part of my brain thought I should go back to Taiwan if I could. After all, I had a life to return to—I had relationships I cared about, plants to water, a baby goddaughter I missed, and a class I had promised to teach. To stay in the U.S. for an unknown stretch of time meant feeling unmoored, anxious about what was happening here but also about all I had left behind. The other reason, perhaps, was a need for some sense of control. The part of me that had learned to ignore my anxious, overzealous imagination did not want my worst fears to win; maybe proceeding as planned was one way to deny they could.

In the week leading up to my flight, I lay awake at night, my skin bathed in cold sweat, my chest tight, light-headed and unable to swallow ( yes, I did worry that I had contracted COVID-19). My mind conjured up the worst: I would leave and borders everywhere would close; my mother would fall sick and I wouldn’t be able to return to her side; the world’s infrastructure would collapse and I’d never be able to speak to my family again. The possibilities nauseated me.

I began to think about my grandfather a lot, about how he must have replayed the moment he stepped onto the boat to Taiwan over and over in his mind for the rest of his life.

What I’ve learned from my grandfather’s story is that there are terrible, historical moments in which a single choice or act of chance can define an entire life. That knowledge is bound to my bones. Inherited traumas are bodily memories, warnings from our ancestors that the world can change rapidly, that everything we take for granted can be lost to us and we must be prepared for the moment it is. These communal memories are meant to protect us, and yet in “normal” times, dwelling on them can hinder us from moving forward. I constantly worry over the possibility of regret, and I’ve worked hard not to let this fear paralyze me. To suddenly be thrust into my own moment of reckoning, faced with a choice whose weight I might not know until it was too late—this was a special kind of hell.

I know that I’m not the only person who is experiencing a resurfacing of generational trauma. I’ve seen it on my timeline: friends warned to stock up on food by parents and grandparents who have experienced wartime and famine; folks who once had to hide in place having to do so again. I think of all the people whose cultural histories are informing the decisions they make during this crisis. I think back to my own inherited hoarding tendencies, about how I hate throwing away a single piece of string or square of wrapping paper that can be reused, how I’ve often had the urge to buy gold in case paper money becomes obsolete.

In the end, I got on that plane. I justified it by telling myself that my fears were an overreaction, that what made the most sense was to return to the life I had created in Taiwan. Even so, I barely made it on the flight. I’d been pulled out of my boarding line when the airline got word of a decision, made by the Taiwanese government only minutes earlier, to bar entry for foreigners without alien resident cards. Standing among confused and panicked people, I thought, I am in my novel; I’m trying to get on a “last boat out” and I might be left behind. After an hour of waiting, an airline employee finally let us board; it turned out there had been confusion about when exactly the ban was taking effect.

I wasn’t sure whether I was relieved or upset. On the 16-hour flight over, surrounded by people covered in masks and raincoats and shower caps and goggles, I questioned whether I had made the right choice. Would I live to regret it, the same way my grandfather surely regretted getting on that boat? Even now, a month since my return, the unease of the unanswerable tumbles daily through my chest.

I’m lucky that I live in a different era from my grandparents, that I can still interact with my family via text and videochat. That even an ocean away, I’m still up to date on how and what they’re doing every day. My grandfather didn’t have that luxury. And I try to remind myself that my situation is different. My family might not be physically close, but they’re still in my life. That’s no small thing.

When this is all over, I joke to people, when I finally sit down to edit my novel, it will be better for this “method training.” I let myself believe things will be normal. I wonder though, if I’ll ever be able to truly cram my fear back into the space it had once occupied, the one labeled “irrational thoughts.” I wonder if any of us who have these histories can ever push them deep below the surface again.

For so long, I told myself to ignore my worries because I lived in a different world from my grandparents, and I do—I know I’m privileged in this way. But I also know how quickly an “unfounded fear” can become “normal caution,” how much context matters. In Taiwan, where the number of COVID-19 cases has remained low and life goes on with relative normalcy, I am a nervous outlier, still afraid of leaving the safety of my apartment two weeks after my mandatory quarantine ended, and spraying down every surface with alcohol when I do, because every surface feels like an invisible threat.

I think about my grandfather, what he must have worried about when the terrible thing actually did happen, how he must have never quite stopped being afraid it could happen again. But what I also know about my grandfather is that he lived and danced and loved. He did more than survive. And maybe that’s also part of what I’m meant to learn from him—that there will always be uncertainty and the unknown, but also, there will always be a way to live.