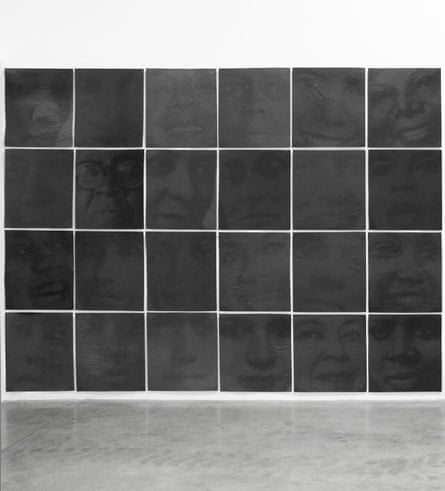

In 2016, curator Susan Tallman was at an art fair in Chicago when one piece of artwork stopped her in her tracks. It was a series of 48 portraits of prominent African Americans, from Nina Simone to Maya Angelou, by Samuel Levi Jones, who had hung them all in a grid.

“From a distance, I thought it was an abstract grid, but it’s only when I walked closer, I saw there were faces in it,” said Tallman. “Then, the penny drops when you think about Gerhard Richter’s 48 Portraits.”

She’s referring to Richter, the German artist who created 48 portraits of influential white men in literature, science, philosophy and music. From Albert Einstein to Oscar Wilde and Thomas Mann, Richter created portraits of 48 men born between 1824 and 1904, with their faces modeled after encyclopedia portraits, which he found from 1971 and 1998.

But the 48 portraits by Jones point to a different history. “It struck me as such a powerful device to get you to pay attention,” said Tallman. “Sam thought about all the people who got left out of history.”

This artwork and more are part of the Edge of Visibility, an exhibition on view at the International Print Center of New York. From works by Kerry James Marshall, Chris Ofili and William Kentridge, the artworks touch upon racial, social and political visibility, and what is often overlooked.

Tallman, the curator of the exhibit, wanted to shed light on the issue in a time when so many communities are unnoticed. “It has this power to make you think – how do I start looking? How do I become more conscientious about trying to see what isn’t being made obvious to me?” said Tallman. “I think that is the key component, especially in America right now, asking ourselves: ‘How do we start looking at what’s not being fed to us?’”

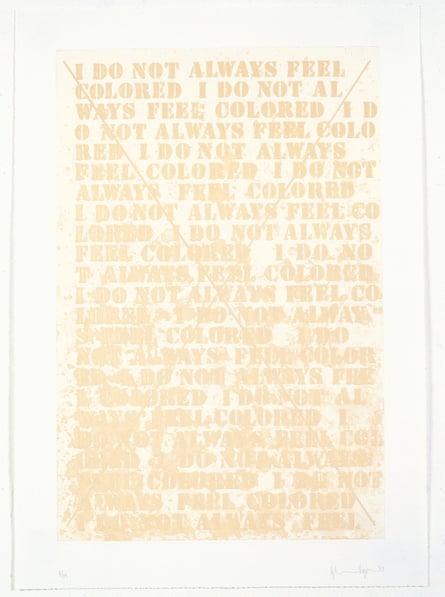

The exhibit features an artwork by former US president Barack Obama’s favorite artist, Glenn Ligon, who quotes the 20th-century African American author, Zora Neale Hurston, for an artwork that reads: “I feel most colored when I am thrown against a white background.” The piece, which quotes Hurston’s 1928 essay How It Feels To Be Colored Me, is written in beige – something that could be compared to Caucasian flesh tone.

“It’s his flip on what we expect when we talk about race in America,” said Tallman. “Instead of talking about experiences if you happen to be black, to extend to everyone, through this piece, it’s symbolically ‘white’ on white paper.”

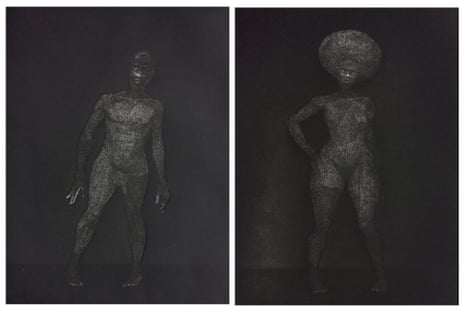

A diptych by Kerry James Marshall of black nude figures as Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein is also in the exhibit. In reference to his artwork, the artist explained in 2016: “If a part of the goal is to normalize the presence of those figures in museums and artworks you have to have a sustained engagement with those figures under a variety of conditions and circumstances so that now, it becomes ordinary to you.”

There is also a screen print of a black flag by artist Megan Foster, captured at half-mast in darkness. “It’s an elegy for democracy itself,” said Tallman. “It was done the day after the 2016 presidential election, literally the morning after.”

As for Jones’s 48 portraits of African Americans, they’re shown on black paper, almost hidden. This could partly be why the title of the artwork is meant to look like under-exposed photography, as a metaphor for racist histories.

“Race-based visibility and inclusion in recent times has been growing more and more,” said the artist. “With this comes greater resistance and the attempt to dismantle progression. It is important that those who have been forcibly marginalized, realize visibility must continue, and with strong unity. It is up to the oppressed to break free of the antics that keep others in power.”

Jones had his own kind of reaction to Richter’s 48 portraits when he first discovered the artwork. “I was confused as to why one would paint portraits of only white men,” said Jones. “I also asked myself why these paintings would be elevated.”

But there might be another kind of hidden visibility there, as well. “The representation of white men was predominant over non-white males, but maybe Richter was questioning what I was questioning,” said Jones, “or perhaps, that’s a stretch.”

Edge of Visibility is on view at International Print Center New York until 19 December

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion